The Two Babylons Chapter IV. Doctrine and Discipline

Continued from The Two Babylons Chapter III. Festivals. Section IV — The Feast of the Assumption

Section I — Baptismal Regeneration

When Linacer, a distinguished physician, but bigoted Romanist, in the reign of Henry VIII first fell in with the New Testament, after reading it for a while, he tossed it from him with impatience and a great oath, exclaiming, “Either this book is not true, or we are not Christians.” He saw at once that the system of Rome and the system of the New Testament were directly opposed to one another; and no one who impartially compares the two systems can come to any other conclusion. In passing from the Bible to the Breviary, it is like passing from light to darkness. While the one breathes glory to God in the highest, peace on earth, and good will to men, the other inculcates all that is dishonouring to the Most High, and ruinous to the moral and spiritual welfare of mankind. How came it that such pernicious doctrines and practices were embraced by the Papacy? Was the Bible so obscure or ambiguous that men naturally fell into the mistake of supposing that it required them to believe and practise the very opposite of what it did? No; the doctrine and discipline of the Papacy were never derived from the Bible. The fact that wherever it has the power, it lays the reading of the Bible under its ban, and either consigns that choicest gift of heavenly love to the flames, or shuts it up under lock and key, proves this of itself. But it can be still more conclusively established. A glance at the main pillars of the Papal system will sufficiently prove that its doctrine and discipline, in all essential respects, have been derived from Babylon. Let the reader now scan the evidence.

Baptismal Regeneration

It is well known that regeneration by baptism is a fundamental article of Rome, yea, that it stands at the very threshold of the Roman system. So important, according to Rome, is baptism for this purpose, that, on the one hand, it is pronounced of “absolute necessity for salvation,” * insomuch that infants dying without it cannot be admitted to glory; and on the other, its virtues are so great, that it is declared in all cases infallibly to “regenerate us by a new spiritual birth, making us children of God”:–it is pronounced to be “the first door by which we enter into the fold of Jesus Christ, the first means by which we receive the grace of reconciliation with God; therefore the merits of His death are by baptism applied to our souls in so superabundant a manner, as fully to satisfy Divine justice for all demands against us, whether for original or actual sin.”

* Bishop HAY’S Sincere Christian. There are two exceptions to this statement; the case of an infidel converted in a heathen land, where it is impossible to get baptism, and the case of a martyr “baptised,” as it is called, “in his own blood”; but in all other cases, whether of young or old, the necessity is “absolute.”

Now, in both respects this doctrine is absolutely anti-Scriptural; in both it is purely Pagan. It is anti-Scriptural, for the Lord Jesus Christ has expressly declared that infants, without the slightest respect to baptism or any external ordinance whatever, are capable of admission into all the glory of the heavenly world:

“Suffer the little children to come unto Me, and forbid them not; for of such is the kingdom of heaven.“

John the Baptist, while yet in his mother’s womb was so filled with joy at the advent of the Saviour, that, as soon as Mary’s salutation sounded in the ears of his own mother, the unborn babe “leaped in the womb for joy.” Had that child died at the birth, what could have excluded it from “the inheritance of the saints in light” for which it was so certainly “made meet”? Yet the Roman Catholic Bishop Hay, in defiance of very principle of God’s Word, does not hesitate to pen the following: “Question: What becomes of young children who die without baptism? Answer: If a young child were put to death for the sake of Christ, this would be to it the baptism of blood, and carry it to heaven; but except in this case, as such infants are incapable of having the desire of baptism, with the other necessary dispositions, if they are not actually baptized with water, THEY CANNOT GO TO HEAVEN.” As this doctrine never came from the Bible, whence came it? It came from heathenism. The classic reader cannot fail to remember where, and in what melancholy plight, Aeneas, when he visited the infernal regions, found the souls of unhappy infants who had died before receiving, so to speak, “the rites of the Church”:

“Before the gates the cries of babes new-born,

Whom fate had from their tender mothers torn,

Assault his ears.”

These wretched babes, to glorify the virtue and efficacy of the mystic rites of Paganism, are excluded from the Elysian Fields, the paradise of the heathen, and have among their nearest associates no better company than that of guilty suicides:

“The next in place and punishment are they

Who prodigally threw their souls away,

Fools, who, repining at their wretched state,

And loathing anxious life, suborned their fate.” *

* Virgil, DRYDEN’S translation. Between the infants and the suicides one other class is interposed, that is, those who on earth have been unjustly condemned to die. Hope is held out for these, but no hope is held out for the babes.

So much for the lack of baptism. Then as to its positive efficacy when obtained, the Papal doctrine is equally anti-Scriptural. There are professed Protestants who hold the doctrine of Baptismal Regeneration; but the Word of God knows nothing of it. The Scriptural account of baptism is, not that it communicates the new birth, but that it is the appointed means of signifying and sealing that new birth where it already exists. In this respect baptism stands on the very same ground as circumcision. Now, what says God’s Word of the efficacy of circumcision? This it says, speaking of Abraham:

“He received the sign of circumcision, a seal of the righteousness of the faith which he had, yet being uncircumcised” (Rom 4:11).

Circumcision was not intended to make Abraham righteous; he was righteous already before he was circumcised. But it was intended to declare him righteous, to give him the more abundant evidence in his own consciousness of his being so. Had Abraham not been righteous before his circumcision, his circumcision could not have been a seal, could not have given confirmation to that which did not exist. So with baptism, it is “a seal of the righteousness of the faith” which the man “has before he is baptized“; for it is said, “He that believeth, and is baptized, shall be saved” (Mark 16:16). Where faith exists, if it be genuine, it is the evidence of a new heart, of a regenerated nature; and it is only on the profession of that faith and regeneration in the case of an adult, that he is admitted to baptism. Even in the case of infants, who can make no profession of faith or holiness, the administration of baptism is not for the purpose of regenerating them, or making them holy, but of declaring them “holy,” in the sense of being fit for being consecrated, even in infancy, to the service of Christ, just as the whole nation of Israel, in consequence of their relation to Abraham, according to the flesh, were “holy unto the Lord.” If they were not, in that figurative sense, “holy,” they would not be fit subjects for baptism, which is the “seal” of a holy state. But the Bible pronounces them, in consequence of their descent from believing parents, to be “holy,” and that even where only one of the parents is a believer:

“The unbelieving husband is sanctified by the wife, and the unbelieving wife is sanctified by the husband; else were your children unclean, but now they are HOLY” (1 Cor 7:14).

It is in consequence of, and solemnly to declare, that “holiness,” with all the responsibilities attaching to it, that they are baptized. That “holiness,” however, is very different from the “holiness” of the new nature; and although the very fact of baptism, if Scripturally viewed and duly improved, is, in the hand of the good Spirit of God, an important means of making that “holiness” a glorious reality, in the highest sense of the term, yet it does not in all cases necessarily secure their spiritual regeneration. God may, or may not, as He sees fit, give the new heart, before, or at, or after baptism; but manifest it is, that thousands who have been duly baptized are still unregenerate, are still in precisely the same position as Simon Magus, who, after being canonically baptized by Philip, was declared to be “in the gall of bitterness and the bond of iniquity” (Acts 7:23). The doctrine of Rome, however, is, that all who are canonically baptized, however ignorant, however immoral, if they only give implicit faith to the Church, and surrender their consciences to the priests, are as much regenerated as ever they can be, and that children coming from the waters of baptism are entirely purged from the stain of original sin. Hence we find the Jesuit missionaries in India boasting of making converts by thousands, by the mere fact of baptising them, without the least previous instruction, in the most complete ignorance of the truths of Christianity, on their mere profession of submission to Rome.

This doctrine of Baptismal Regeneration also is essentially Babylonian. Some may perhaps stumble at the idea of regeneration at all having been known in the Pagan world; but if they only go to India, they will find at this day, the bigoted Hindoos, who have never opened their ears to Christian instruction, as familiar with the term and the idea as ourselves. The Brahmins make it their distinguishing boast that they are “twice-born” men, and that, as such, they are sure of eternal happiness. Now, the same was the case in Babylon, and there the new birth was conferred by baptism. In the Chaldean mysteries, before any instruction could be received, it was required first of all, that the person to be initiated submit to baptism in token of blind and implicit obedience. We find different ancient authors bearing direct testimony both to the fact of this baptism and the intention of it. “In certain sacred rites of the heathen,” says Tertullian, especially referring to the worship of Isis and Mithra, “the mode of initiation is by baptism.” The term “initiation” clearly shows that it was to the Mysteries of these divinities he referred. This baptism was by immersion, and seems to have been rather a rough and formidable process; for we find that he who passed through the purifying waters, and other necessary penances, “if he survived, was then admitted to the knowledge of the Mysteries.” (Elliae Comment. in S. GREG. NAZ.) To face this ordeal required no little courage on the part of those who were initiated. There was this grand inducement, however, to submit, that they who were thus baptized were, as Tertullian assures us, promised, as the consequence, “REGENERATION, and the pardon of all their perjuries.” Our own Pagan ancestors, the worshippers of Odin, are known to have practised baptismal rites, which, taken in connection with their avowed object in practising them, show that, originally, at least, they must have believed that the natural guilt and corruption of their new-born children could be washed away by sprinkling them with water, or by plunging them, as soon as born, into lakes or rivers.

Yea, on the other side of the Atlantic, in Mexico, the same doctrine of baptismal regeneration was found in full vigour among the natives, when Cortez and his warriors landed on their shores. The ceremony of Mexican baptism, which was beheld with astonishment by the Spanish Roman Catholic missionaries, is thus strikingly described in Prescott’s Conquest of Mexico: “When everything necessary for the baptism had been made ready, all the relations of the child were assembled, and the midwife, who was the person that performed the rite of baptism, * was summoned. At early dawn, they met together in the courtyard of the house. When the sun had risen, the midwife, taking the child in her arms, called for a little earthen vessel of water, while those about her placed the ornaments, which had been prepared for baptism, in the midst of the court. To perform the rite of baptism, she placed herself with her face toward the west, and immediately began to go through certain ceremonies…After this she sprinkled water on the head of the infant, saying, ‘O my child, take and receive the water of the Lord of the world, which is our life, which is given for the increasing and renewing of our body. It is to wash and to purify. I pray that these heavenly drops may enter into your body, and dwell there; that they may destroy and remove from you all the evil and sin which was given you before the beginning of the world, since all of us are under its power’…She then washed the body of the child with water, and spoke in this manner: ‘Whencesoever thou comest, thou that art hurtful to this child, leave him and depart from him, for he now liveth anew, and is BORN ANEW; now he is purified and cleansed afresh, and our mother Chalchivitylcue [the goddess of water] bringeth him into the world.’ Having thus prayed, the midwife took the child in both hands, and, lifting him towards heaven, said, ‘O Lord, thou seest here thy creature, whom thou hast sent into the world, this place of sorrow, suffering, and penitence. Grant him, O Lord, thy gifts and inspiration, for thou art the Great God, and with thee is the great goddess.'”

* As baptism is absolutely necessary to salvation, Rome also authorises midwives to administer baptism. In Mexico the midwife seems to have been a “priestess.”

Here is the opus operatum without mistake. Here is baptismal regeneration and exorcism too, * as thorough and complete as any Romish priest or lover of Tractarianism could desire.

* In the Romish ceremony of baptism, the first thing the priest does is to exorcise the devil out of the child to be baptized in these words, “Depart from him, thou unclean spirit, and give place to the Holy Ghost the Comforter.” (Sincere Christian) In the New Testament there is not the slightest hint of any such exorcism accompanying Christian Baptism. It is purely Pagan.

Does the reader ask what evidence is there that Mexico had derived this doctrine from Chaldea? The evidence is decisive. From the researches of Humboldt we find that the Mexicans celebrated Wodan as the founder of their race, just as our own ancestors did. The Wodan or Odin of Scandinavia can be proved to be the Adon of Babylon. (see note below) The Wodan of Mexico, from the following quotation, will be seen to be the very same: “According to the ancient traditions collected by the Bishop Francis Nunez de la Vega,” says Humboldt, “the Wodan of the Chiapanese [of Mexico] was grandson of that illustrious old man, who at the time of the great deluge, in which the greater part of the human race perished, was saved on a raft, together with his family. Wodan co-operated in the construction of the great edifice which had been undertaken by men to reach the skies; the execution of this rash project was interrupted; each family received from that time a different language; and the great spirit Teotl ordered Wodan to go and people the country of Anahuac.” This surely proves to demonstration whence originally came the Mexican mythology and whence also that doctrine of baptismal regeneration which the Mexicans held in common with Egyptian and Persian worshippers of the Chaldean Queen of Heaven. Prestcott, indeed, has cast doubts on the genuiness of this tradition, as being too exactly coincident with the Scriptural history to be easily believed. But the distinguished Humboldt, who had carefully examined the matter, and who had no prejudice to warp him, expresses his full belief in its correctness; and even from Prestcott’s own interesting pages, it may be proved in every essential particular, with the single exception of the name of Wodan, to which he makes no reference. But, happily, the fact that that name had been borne by some illustrious hero among the supposed ancestors of the Mexican race, is put beyond all doubt by the singular circumstance that the Mexicans had one of their days called Wodansday, exactly as we ourselves have. This, taken in connection with all the circumstances, is a very striking proof, at once of the unity of the human race, and of the wide-spread diffusion of the system that began at Babel.

If the question arise, How came it that the Bayblonians themselves adopted such a doctrine as regeneration by baptism, we have light also on that. In the Babylonian Mysteries, the commemoration of the flood, of the ark, and the grand events in the life of Noah, was mingled with the worship of the Queen of Heaven and her son. Noah, as having lived in two worlds, both before the flood and after it, was called “Dipheus,” or “twice-born,” and was represented as a god with two heads looking in opposite directions, the one old, and the other young (see figure 34). Though we have seen that the two-headed Janus in one aspect had reference to Cush and his son, Nimrod, viewed as one god, in a two-fold capacity, as the Supreme, and Father of all the deified “mighty ones,” yet, in order to gain for him the very authority and respect essential to constitute him properly the head of the great system of idolatry that the apostates inaugurated, it was necessary to represent him as in some way or other identified with the great patriarch, who was the Father of all, and who had so miraculous a history. Therefore in the legends of Janus, we find mixed up with other things derived from an entirely different source, statements not only in regard to his being the “Father of the world,” but also his being “the inventor of ships,” which plainly have been borrowed from the history of Noah; and therefore, the remarkable way in which he is represented in the figure here presented to the reader may confidently be concluded to have been primarily suggested by the history of the great Diluvian patriarch, whose integrity in his two-fold life is so particularly referred to in the Scripture, where it is said (Gen 6:9), “Noah was just a man, and perfect in his generations,” that is, in his life before the flood, and in his life after it. The whole mythology of Greece and Rome, as well as Asia, is full of the history and deeds of Noah, which it is impossible to misunderstand. In India, the god Vishnu, “the Preserver,” who is celebrated as having miraculously preserved one righteous family at the time when the world was drowned, not only has the story of Noah wrought up with his legend, but is called by his very name. Vishnu is just the Sanscrit form of the Chaldee “Ish-nuh,” “the man Noah,” or the “Man of rest.” In the case of Indra, the “king of the gods,” and god of rain, which is evidently only another form of the same god, the name is found in the precise form of Ishnu. Now, the very legend of Vishnu, that pretends to make him no mere creature, but the supreme and “eternal god,” shows that this interpretation of the name is no mere unfounded imagination. Thus is he celebrated in the “Matsya Puran”: “The sun, the wind, the ether, all things incorporeal, were absorbed into his Divine essence; and the universe being consumed, the eternal and omnipotent god, having assumed an ancient form, REPOSED mysteriously upon the surface of that (universal) ocean. But no one is capable of knowing whether that being was then visible or invisible, or what the holy name of that person was, or what the cause of his mysterious SLUMBER. Nor can any one tell how long he thus REPOSED until he conceived the thought of acting; for no one saw him, no one approached him, and none can penetrate the mystery of his real essence.” (Col. KENNEDY’S Hindoo Mythology) In conformity with this ancient legend, Vishnu is still represented as sleeping four months every year. Now, connect this story with the name of Noah, the man of “Rest,” and with his personal history during the period of the flood, when the world was destroyed, when for forty days and forty nights all was chaos, when neither sun nor moon nor twinkling star appeared, when sea and sky were mingled, and all was one wide universal “ocean,” on the bosom of which the patriarch floated, when there was no human being to “approach” him but those who were with him in the ark, and “the mystery of his real essence is penetrated” at once, “the holy name of that person” is ascertained, and his “mysterious slumber” fully accounted for.

(see figure 34). Though we have seen that the two-headed Janus in one aspect had reference to Cush and his son, Nimrod, viewed as one god, in a two-fold capacity, as the Supreme, and Father of all the deified “mighty ones,” yet, in order to gain for him the very authority and respect essential to constitute him properly the head of the great system of idolatry that the apostates inaugurated, it was necessary to represent him as in some way or other identified with the great patriarch, who was the Father of all, and who had so miraculous a history. Therefore in the legends of Janus, we find mixed up with other things derived from an entirely different source, statements not only in regard to his being the “Father of the world,” but also his being “the inventor of ships,” which plainly have been borrowed from the history of Noah; and therefore, the remarkable way in which he is represented in the figure here presented to the reader may confidently be concluded to have been primarily suggested by the history of the great Diluvian patriarch, whose integrity in his two-fold life is so particularly referred to in the Scripture, where it is said (Gen 6:9), “Noah was just a man, and perfect in his generations,” that is, in his life before the flood, and in his life after it. The whole mythology of Greece and Rome, as well as Asia, is full of the history and deeds of Noah, which it is impossible to misunderstand. In India, the god Vishnu, “the Preserver,” who is celebrated as having miraculously preserved one righteous family at the time when the world was drowned, not only has the story of Noah wrought up with his legend, but is called by his very name. Vishnu is just the Sanscrit form of the Chaldee “Ish-nuh,” “the man Noah,” or the “Man of rest.” In the case of Indra, the “king of the gods,” and god of rain, which is evidently only another form of the same god, the name is found in the precise form of Ishnu. Now, the very legend of Vishnu, that pretends to make him no mere creature, but the supreme and “eternal god,” shows that this interpretation of the name is no mere unfounded imagination. Thus is he celebrated in the “Matsya Puran”: “The sun, the wind, the ether, all things incorporeal, were absorbed into his Divine essence; and the universe being consumed, the eternal and omnipotent god, having assumed an ancient form, REPOSED mysteriously upon the surface of that (universal) ocean. But no one is capable of knowing whether that being was then visible or invisible, or what the holy name of that person was, or what the cause of his mysterious SLUMBER. Nor can any one tell how long he thus REPOSED until he conceived the thought of acting; for no one saw him, no one approached him, and none can penetrate the mystery of his real essence.” (Col. KENNEDY’S Hindoo Mythology) In conformity with this ancient legend, Vishnu is still represented as sleeping four months every year. Now, connect this story with the name of Noah, the man of “Rest,” and with his personal history during the period of the flood, when the world was destroyed, when for forty days and forty nights all was chaos, when neither sun nor moon nor twinkling star appeared, when sea and sky were mingled, and all was one wide universal “ocean,” on the bosom of which the patriarch floated, when there was no human being to “approach” him but those who were with him in the ark, and “the mystery of his real essence is penetrated” at once, “the holy name of that person” is ascertained, and his “mysterious slumber” fully accounted for.

Now, wherever Noah is celebrated, whether by the name of Saturn, “the hidden one,”–for that name was applied to him as well as to Nimrod, on account of his having been “hidden” in the ark, in the “day of the Lord’s fierce anger,”–or, “Oannes,” or “Janus,” the “Man of the Sea,” he is generally described in such a way as shows that he was looked upon as Diphues, “twice-born,” or “regenerate.” The “twice-born” Brahmins, who are all so many gods upon earth, by the very title they take to themselves, show that the god whom they represent, and to whose prerogatives they lay claim, had been known as the “twice-born” god. The connection of “regeneration” with the history of Noah, comes out with special evidence in the accounts handed down to us of the Mysteries as celebrated in Egypt. The most learned explorers of Egyptian antiquities, including Sir Gardiner Wilkinson, admit that the story of Noah was mixed up with the story of Osiris. The ship of Isis, and the coffin of Osiris, floating on the waters, point distinctly to that remarkable event. There were different periods, in different places in Egypt, when the fate of Osiris was lamented; and at one time there was more special reference to the personal history of “the mighty hunter before the Lord,” and at another to the awful catastrophe through which Noah passed. In the great and solemn festival called “The Disappearance of Osiris,” it is evident that it is Noah himself who was then supposed to have been lost. The time when Osiris was “shut up in his coffin,” and when that coffin was set afloat on the waters, as stated by Plutarch, agrees exactly with the period when Noah entered the ark. That time was “the 17th day of the month Athyr, when the overflowing of the Nile had ceased, when the nights were growing long and the days decreasing.” The month Athyr was the second month after the autumnal equinox, at which time the civil year of the Jews and the patriarchs began. According to this statement, then, Osiris was “shut up in his coffin” on the 17th day of the second month of the patriarchal year. Compare this with the Scriptural account of Noah’s entering into the ark, and it will be seen how remarkably they agree (Gen 7:11):

“In the six hundredth year of Noah’s life, in the SECOND MONTH, in the SEVENTEENTH DAY of the month, were all the fountains of the great deep broken up; in the self-same day entered Noah into the ark.“

The period, too, that Osiris (otherwise Adonis) was believed to have been shut up in his coffin, was precisely the same as Noah was confined in the ark, a whole year. *

* APOLLODORUS. THEOCRITUS, Idyll. Theocritus is speaking of Adonis as delivered by Venus from Acheron, or the infernal regions, after being there for a year; but as the scene is laid in Egypt, it is evident that it is Osiris he refers to, as he was the Adonis of the Egyptians.

Now, the statements of Plutarch demonstrate that, as Osiris at this festival was looked upon as dead and buried when put into his ark or coffin, and committed to the deep, so, when at length he came out of it again, that new state was regarded as a state of “new life,” or “REGENERATION.” *

* PLUTARCH, De Iside et Osiride. It was in the character of Pthah-Sokari-Osiris that he was represented as having been thus “buried” in the waters. In his own character, simply as Osiris, he had another burial altogether.

There seems every reason to believe that by the ark and the flood God actually gave to the patriarchal saints, and especially to righteous Noah, a vivid typical representation of the power of the blood and Spirit of Christ, at once in saving from wrath, and cleansing from all sin–a representation which was a most cheering “seal” and confirmation to the faith of those who really believed. To this Peter seems distinctly to allude, when he says, speaking of this very event, “The like figure whereunto baptism doth also now save us.” Whatever primitive truth the Chaldean priests held, they utterly perverted and corrupted it. They willingly overlooked the fact, that it was “the righteousness of the faith” which Noah “had before” the flood, that carried him safely through the avenging waters of that dread catastrophe, and ushered him, as it were, from the womb of the ark, by a new birth, into a new world, when on the ark resting on Mount Ararat, he was released from his long confinement. They led their votaries to believe that, if they only passed through the baptismal waters, and the penances therewith connected, that of itself would make them like the second father of mankind, “Diphueis,” “twice-born,” or “regenerate,” would entitle them to all the privileges of “righteous” Noah, and give them that “new birth” (palingenesia) which their consciences told them they so much needed. The Papacy acts on precisely the same principle; and from this very source has its doctrine of baptismal regeneration been derived, about which so much has been written and so many controversies been waged. Let men contend as they may, this, and this only, will be found to be the real origin of the anti-Scriptural dogma. *

* There have been considerable speculations about the meaning of the name Shinar, as applied to the region of which Babylon was the capital. Do not the facts above stated cast light on it? What so likely a derivation of this name as to derive it from “shene,” “to repeat,” and “naar,” “childhood.” The land of “Shinar,” then, according to this view, is just the land of the “Regenerator.”

The reader has seen already how faithfully Rome has copied the Pagan exorcism in connection with baptism. All the other peculiarities attending the Romish baptism, such as the use of salt, spittle, chrism, or anointing with oil, and marking the forehead with the sign of the cross, are equally Pagan. Some of the continental advocates of Rome have admitted that some of these at least have not been derived from Scripture. Thus Jodocus Tiletanus of Louvaine, defending the doctrine of “Unwritten Tradition,” does not hesitate to say, “We are not satisfied with that which the apostles or the Gospel do declare, but we say that, as well before as after, there are divers matters of importance and weight accepted and received out of a doctrine which is nowhere set forth in writing. For we do blesse the water wherewith we baptize, and the oyle wherewith we annoynt; yea, and besides that, him that is christened. And (I pray you) out of what Scripture have we learned the same? Have we it not of a secret and unwritten ordinance? And further, what Scripture hath taught us to grease with oyle? Yea, I pray you, whence cometh it, that we do dype the childe three times in the water? Doth it not come out of this hidden and undisclosed doctrine, which our forefathers have received closely without any curiosity, and do observe it still.” This learned divine of Louvaine, of course, maintains that “the hidden and undisclosed doctrine” of which he speaks, was the “unwritten word” handed down through the channel of infallibility, from the Apostles of Christ to his own time. But, after what we have already seen, the reader will probably entertain a different opinion of the source from which the hidden and undisclosed doctrine must have come. And, indeed, Father Newman himself admits, in regard to “holy water” (that is, water impregnated with “salt,” and consecrated), and many other things that were, as he says, “the very instruments and appendages of demon-worship”–that they were all of “Pagan” origin, and “sanctified by adoption into the Church.” What plea, then, what palliation can he offer, for so extraordinary an adoption? Why, this: that the Church had “confidence in the power of Christianity to resist the infection of evil,” and to transmute them to “an evangelical use.” What right had the Church to entertain any such “confidence”? What fellowship could light have with darkness? what concord between Christ and Belial? Let the history of the Church bear testimony to the vanity, yea, impiety of such a hope. Let the progress of our inquiries shed light upon the same. At the present stage, there is only one of the concomitant rites of baptism to which I will refer–viz., the use of “spittle” in that ordinance; and an examination of the very words of the Roman ritual, in applying it, will prove that its use in baptism must have come from the Mysteries. The following is the account of its application, as given by Bishop Hay: “The priest recites another exorcism, and at the end of it touches the ear and nostrils of the person to be baptized with a little spittle, saying, ‘Ephpheta, that is, Be thou opened into an odour of sweetness; but be thou put to flight, O Devil, for the judgment of God will be at hand.'” Now, surely the reader will at once ask, what possible, what conceivable connection can there be between spittle, and an “odour of sweetness“? If the secret doctrine of the Chaldean mysteries be set side by side with this statement, it will be seen that, absurd and nonsensical as this collocation of terms may appear, it was not at random that “spittle” and an “odour of sweetness” were brought together.

We have seen already how thoroughly Paganism was acquainted with the attributes and work of the promised Messiah, though all that acquaintance with these grand themes was used for the purpose of corrupting the minds of mankind, and keeping them in spiritual bondage. We have now to see that, as they were well aware of the existence of the Holy Spirit, so, intellectually, they were just as well acquainted with His work, though their knowledge on that subject was equally debased and degraded. Servius, in his comments upon Virgil’s First Georgic, after quoting the well known expression, “Mystica vannus Iacchi,” “the mystic fan of Bacchus,” says that that “mystic fan” symbolised the “purifying of souls.” Now, how could the fan be a symbol of the purification of souls? The answer is, The fan is an instrument for producing “wind”; * and in Chaldee, as has been already observed, it is one and the same word which signifies “wind” and the “Holy Spirit.”

* There is an evident allusion to the “mystic fan” of the Babylonian god, in the doom of Babylon, as pronounced by Jeremiah 51:1, 2: “Thus saith the Lord, Behold, I will raise up against Babylon, and against them that dwell in the midst of them that rise up against me, a destroying wind; and will send unto Babylon fanners, that shall fan her, and shall empty her land.”

There can be no doubt, that, from the very beginning, the “wind” was one of the Divine patriarchal emblems by which the power of the Holy Ghost was shadowed forth, even as our Lord Jesus Christ said to Nicodemus,

“The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh or whither it goeth: so is every one that is born of the Spirit.“

Hence, when Bacchus was represented with “the mystic fan,” that was to declare him to be the mighty One with whom was “the residue of the Spirit.” Hence came the idea of purifying the soul by means of the wind, according to the description of Virgil, who represents the stain and pollution of sin as being removed in this very way:

“For this are various penances enjoined,

And some are hung to bleach upon the WIND.”

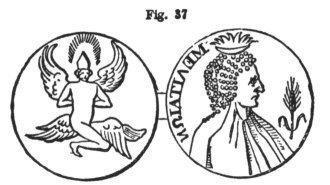

Hence the priests of Jupiter (who was originally just another form of Bacchus), (see figure 35), were called Flamens, * — that is Breathers, or bestowers of the Holy Ghost, by breathing upon their votaries.

Figure 35

Figure 35

Now, in the Mysteries, the “spittle” was just another symbol for the same thing. In Egypt, through which the Babylonian system passed to Western Europe, the name of the “Pure or Purifying Spirit” was “Rekh” (BUNSEN). But “Rekh” also signified “spittle” (PARKHURST’S Lexicon); so that to anoint the nose and ears of the initiated with “spittle,” according to the mystic system, was held to be anointing them with the “Purifying Spirit.” That Rome in adopting the “spittle” actually copied from some Chaldean ritual in which “spittle” was the appointed emblem of the “Spirit,” is plain from the account which she gives in her own recognised formularies of the reason for anointing the ears with it. The reason for anointing the ears with “spittle” says Bishop Hay, is because “by the grace of baptism, the ears of our soul are opened to hear the Word of God, and the inspirations of His Holy Spirit.” But what, it may be asked, has the “spittle” to do with the “odour of sweetness”? I answer, The very word “Rekh,” which signified the “Holy Spirit,” and was visibly represented by the “spittle,” was intimately connected with “Rikh,” which signifies a “fragrant smell,” or “odour of sweetness.” Thus, a knowledge of the Mysteries gives sense and a consistent meaning to the cabalistic saying addressed by the Papal baptiser to the person about to be baptized, when the “spittle” is daubed on his nose and ears, which otherwise would have no meaning at all–“Ephpheta, Be thou opened into an odour of sweetness.” While this was the primitive truth concealed under the “spittle,” yet the whole spirit of Paganism was so opposed to the spirituality of the patriarchal religion, and indeed intended to make it void, and to draw men utterly away from it, while pretending to do homage to it, that among the multitude in general the magic use of “spittle” became the symbol of the grossest superstition. Theocritus shows with what debasing rites it was mixed up in Sicily and Greece; and Persius thus holds up to scorn the people of Rome in his day for their reliance on it to avert the influence of the “evil eye”:

“Our superstitions with our life begin;

The obscene old grandam, or the next of kin,

The new-born infant from the cradle takes,

And first of spittle a lustration makes;

Then in the spawl her middle finger dips,

Anoints the temples, forehead, and the lips,

Pretending force of magic to prevent

By virtue of her nasty excrement.”–DRYDEN

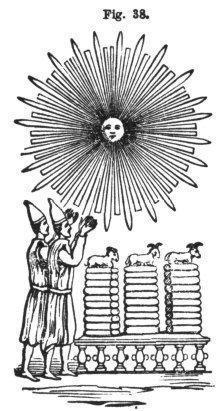

While thus far we have seen how the Papal baptism is just a reproduction of the Chaldean, there is still one other point to be noticed, which makes the demonstration complete. That point is contained in the following tremendous curse fulminated against a man who committed the unpardonable offence of leaving the Church of Rome, and published grave and weighty reasons for so doing: “May the Father, who creates man, curse him! May the Son, who suffered for us, curse him! May the Holy Ghost who suffered for us in baptism, curse him!” I do not stop to show how absolutely and utterly opposed such a curse as this is to the whole spirit of the Gospel. But what I call the reader’s attention to is the astounding statement that “the Holy Ghost suffered for us in baptism.” Where in the whole compass of Scripture could warrant be found for such an assertion as this, or anything that could even suggest it? But let the reader revert to the Babylonian account of the personality of the Holy Ghost, and the amount of blasphemy contained in this language will be apparent. According to the Chaldean doctrine, Semiramis, the wife of Ninus or Nimrod, when exalted to divinity under the name of the Queen of Heaven, came, as we have seen, to be worshipped as Juno, the “Dove”–in other words, the Holy Spirit incarnate. Now, when her husband, for his blasphemous rebellion against the majesty of heaven, was cut off, for a season it was a time of tribulation also for her. The fragments of ancient history that have come down to us give an account of her trepidation and flight, to save herself from her adversaries. In the fables of the mythology, this flight was mystically represented in accordance with what was attributed to her husband. The bards of Greece represented Bacchus, when overcome by his enemies, as taking refuge in the depths of the ocean (see figure 36). Thus, Homer:

“In a mad mood, while Bacchus blindly raged,

Lycurgus drove his trembling bands, confused,

O’er the vast plains of Nusa. They in haste

Threw down their sacred implements, and fled

In fearful dissipation. Bacchus saw

Rout upon rout, and, lost in wild dismay,

Plunged in the deep. Here Thetis in her arms

Received him shuddering at the dire event.”

Figure 36

Figure 36

In Egypt, as we have seen, Osiris, as identified with Noah, was represented, when overcome by his grand enemy Typhon, or the “Evil One,” as passing through the waters. The poets represented Semiramis as sharing in his distress, and likewise seeking safety in the same way. We have seen already, that, under the name of Astarte, she was said to have come forth from the wondrous egg that was found floating on the waters of the Euphrates. Now Manilius tells, in his Astronomical Poetics, what induced her to take refuge in these waters. “Venus plunged into the Babylonia waters,” says he, “to shun the fury of the snake-footed Typhon.” When Venus Urania, or Dione, the “Heavenly Dove,” plunged in deep distress into these waters of Babylon, be it observed what, according to the Chaldean doctrine, this amounted to. It was neither more nor less than saying that the Holy Ghost incarnate in deep tribulation entered these waters, and that on purpose that these waters might be fit, not only by the temporary abode of the Messiah in the midst of them, but by the Spirit’s efficacy thus imparted to them, for giving new life and regeneration, by baptism, to the worshippers of the Chaldean Madonna. We have evidence that the purifying virtue of the waters, which in Pagan esteem had such efficacy in cleansing from guilt and regenerating the soul, was derived in part from the passing of the Mediatorial god, the sun-god and god of fire, through these waters during his humiliation and sojourn in the midst of them; and that the Papacy at this day retains the very custom which had sprung up from that persuasion. So far as heathenism is concerned, the following extracts from Potter and Athenaeus speak distinctly enough: “Every person,” says the former, “who came to the solemn sacrifices [of the Greeks] was purified by water. To which end, at the entrance of the temples there was commonly placed a vessel full of holy water.” How did this water get its holiness? This water “was consecrated,” says Athenaeus, “by putting into it a BURNING TORCH taken from the altar.” The burning torch was the express symbol of the god of fire; and by the light of this torch, so indispensable for consecrating “the holy water,” we may easily see whence came one great part of the purifying virtue of “the water of the loud resounding sea,” which was held to be so efficacious in purging away the guilt and stain of sin, *–even from the sun-god having taken refuge in its waters.

* “All human ills,” says Euripides, in a well known passage, “are washed away by the sea.”

Now this very same method is used in the Romish Church for consecrating the water for baptism. The unsuspicious testimony of Bishop Hay leaves no doubt on this point: “It” [the water kept in the baptismal font], says he, “is blessed on the eve of Pentecost, because it is the Holy Ghost who gives to the waters of baptism the power and efficacy of sanctifying our souls, and because the baptism of Christ is ‘with the Holy Ghost, and with fire‘ (Matt 3:11). In blessing the waters a LIGHTED TORCH is put into the font.” Here, then, it is manifest that the baptismal regenerating water of Rome is consecrated just as the regenerating and purifying water of the Pagans was. Of what avail is it for Bishop Hay to say, with the view of sanctifying superstition and “making apostacy plausible,” that this is done “to represent the fire of Divine love, which is communicated to the soul by baptism, and the light of good example, which all who are baptized ought to give.” This is the fair face put on the matter; but the fact still remains that while the Romish doctrine in regard to baptism is purely Pagan, in the ceremonies connected with the Papal baptism one of the essential rites of the ancient fire-worship is still practised at this day, just as it was practised by the worshippers of Bacchus, the Babylonian Messiah. As Rome keeps up the remembrance of the fire-god passing through the waters and giving virtue to them, so when it speaks of the “Holy Ghost suffering for us in baptism,” it in like manner commemorates the part which Paganism assigned to the Babylonian goddess when she plunged into the waters. The sorrows of Nimrod, or Bacchus, when in the waters were meritorious sorrows. The sorrows of his wife, in whom the Holy Ghost miraculously dwelt, were the same. The sorrows of the Madonna, then, when in these waters, fleeing from Typhon’s rage, were the birth-throes by which children were born to God. And thus, even in the Far West, Chalchivitlycue, the Mexican “goddess of the waters,” and “mother” of all the regenerate, was represented as purging the new-born infant from original sin, and “bringing it anew into the world.” Now, the Holy Ghost was idolatrously worshipped in Babylon under the form of a “Dove.” Under the same form, and with equal idolatry, the Holy Ghost is worshipped in Rome. When, therefore, we read, in opposition to every Scripture principle, that “the Holy Ghost suffered for us in baptism,” surely it must now be manifest who is that Holy Ghost that is really intended. It is no other than Semiramis, the very incarnation of lust and all uncleanness.

Notes

The Identity of the Scandinavian Odin and Adon of Babylon

1. Nimrod, or Adon, or Adonis, of Babylon, was the great war-god. Odin, as is well known, was the same. 2 Nimrod, in the character of Bacchus, was regarded as the god of wine; Odin is represented as taking no food but wine. For thus we read in the Edda: “As to himself he [Odin] stands in no need of food; wine is to him instead of every other aliment, according to what is said in these verses: The illustrious father of armies, with his own hand, fattens his two wolves; but the victorious Odin takes no other nourishment to himself than what arises from the unintermitted quaffing of wine” (MALLET, 20th Fable). 3. The name of one of Odin’s sons indicates the meaning of Odin’s own name. Balder, for whose death such lamentations were made, seems evidently just the Chaldee form of Baal-zer, “The seed of Baal”; for the Hebrew z, as is well known, frequently, in the later Chaldee, becomes d. Now, Baal and Adon both alike signify “Lord”; and, therefore, if Balder be admitted to be the seed or son of Baal, that is as much as to say that he is the son of Adon; and, consequently, Adon and Odin must be the same. This, of course, puts Odin a step back; makes his son to be the object of lamentation and not himself; but the same was the case also in Egypt; for there Horus the child was sometimes represented as torn in pieces, as Osiris had been. Clemens Alexandrinus says (Cohortatio), “they 03 lament an infant torn in pieces by the Titans.” The lamentations for Balder are very plainly the counterpart of the lamentations for Adonis; and, of course, if Balder was, as the lamentations prove him to have been, the favourite form of the Scandinavian Messiah, he was Adon, or “Lord,” as well as his father. 4. Then, lastly, the name of the other son of Odin, the mighty and warlike Thor, strengthens all the foregoing conclusions. Ninyas, the son of Ninus or Nimrod, on his father’s death, when idolatry rose again, was, of course, from the nature of the mystic system, set up as Adon, “the Lord.” Now, as Odin had a son called Thor, so the second Assyrian Adon had a son called Thouros. The name Thouros seems just to be another form of Zoro, or Doro, “the seed”; for Photius tells us that among the Greeks Thoros signified “Seed.” The D is often pronounced as Th,–Adon, in the pointed Hebrew, being pronounced Athon.

Section II — Justification by Works

The worshippers of Nimrod and his queen were looked upon as regenerated and purged from sin by baptism, which baptism received its virtue from the sufferings of these two great Babylonian divinities. But yet in regard to justification, the Chaldean doctrine was that it was by works and merits of men themselves that they must be justified and accepted of God. The following remarks of Christie in his observations appended to Ouvaroff’s Eleusinian Mysteries, show that such was the case: “Mr. Ouvaroff has suggested that one of the great objects of the Mysteries was the presenting to fallen man the means of his return to God. These means were the cathartic virtues–(i.e., the virtues by which sin is removed), by the exercise of which a corporeal life was to be vanquished. Accordingly the Mysteries were termed Teletae, ‘perfections,’ because they were supposed to induce a perfectness of life. Those who were purified by them were styled Teloumenoi and Tetelesmenoi, that is, ‘brought…to perfection,’ which depended on the exertions of the individual.” In the Metamorphosis of Apuleius, who was himself initiated in the mysteries of Isis, we find this same doctrine of human merits distinctly set forth. Thus the goddess is herself represented as addressing the hero of his tale: “If you shall be found to DESERVE the protection of my divinity by sedulous obedience, religious devotion and inviolable chastity, you shall be sensible that it is possible for me, and me alone, to extend your life beyond the limits that have been appointed to it by your destiny.” When the same individual has received a proof of the supposed favour of the divinity, thus do the onlookers express their congratulations: “Happy, by Hercules! and thrice blessed he to have MERITED, by the innocence and probity of his past life, such special patronage of heaven.” Thus was it in life. At death, also, the grand passport into the unseen world was still through the merits of men themselves, although the name of Osiris was, as we shall by-and-by see, given to those who departed in the faith. “When the bodies of persons of distinction” [in Egypt], says Wilkinson, quoting Porphyry, “were embalmed, they took out the intestines and put them into a vessel, over which (after some other rites had been performed for the dead) one of the embalmers pronounced an invocation to the sun in behalf of the deceased.” The formula, according to Euphantus, who translated it from the original into Greek, was as follows: “O thou Sun, our sovereign lord! and all ye Deities who have given life to man, receive me, and grant me an abode with the eternal gods. During the whole course of my life I have scrupulously worshipped the gods my father taught me to adore; I have ever honoured my parents, who begat this body; I have killed no one; I have not defrauded any, nor have I done any injury to any man.” Thus the merits, the obedience, or the innocence of man was the grand plea. The doctrine of Rome in regard to the vital article of a sinner’s justification is the very same. Of course this of itself would prove little in regard to the affiliation of the two systems, the Babylonian and the Roman; for, from the days of Cain downward, the doctrine of human merit and of self-justification has everywhere been indigenous in the heart of depraved humanity. But, what is worthy of notice in regard to this subject is, that in the two systems, it was symbolised in precisely the same way. In the Papal legends it is taught that St. Michael the Archangel has committed to him the balance of God’s justice, and that in the two opposite scales of that balance the merits and the demerits of the departed are put that they may be fairly weighed, the one over against the other, and that as the scale turns to the favourable or unfavourable side they may be justified or condemned as the case may be.

Now, the Chaldean doctrine of justification, as we get light on it from the monuments of Egypt, is symbolised in precisely the same way, except that in the land of Ham the scales of justice were committed to the charge of the god Anubis instead of St. Michael the Archangel, and that the good deeds and the bad seem to have been weighed separately, and a distinct record made of each, so that when both were summed up and the balance struck, judgment was pronounced accordingly. Wilkinson states that Anubis and his scales are often represented; and that in some cases there is some difference in the details. But it is evident from his statements, that the principle in all is the same. The following is the account which he gives of one of these judgment scenes, previous to the admission of the dead to Paradise: “Cerberus is present as the guardian of the gates, near which the scales of justice are erected; and Anubis, the director of the weight, having placed a vase representing the good actions of the deceased in one scale, and the figure or emblem of truth in the other, proceeds to ascertain his claims for admission. If, on being weighed, he is found wanting, he is rejected, and Osiris, the judge of the dead, inclining his sceptre in token of condemnation, pronounces judgment upon him, and condemns his soul to return to earth under the form of a pig or some unclean animal…But if, when the SUM of his deeds are recorded by Thoth [who stands by to mark the results of the different weighings of Anubis], his virtues so far PREDOMINATE as to entitle him to admission to the mansions of the blessed, Horus, taking in his hand the tablet of Thoth, introduces him to the presence of Osiris, who, in his palace, attended by Isis and Nepthys, sits on his throne in the midst of the waters, from which rises the lotus, bearing upon its expanded flowers the four Genii of Amenti.”

The same mode of symbolising the justification by works had evidently been in use in Babylon itself; and, therefore, there was great force in the Divine handwriting on the wall, when the doom of Belshazzar went forth: “Tekel,” “Thou art weighed in the balances, and art found wanting.” In the Parsee system, which has largely borrowed from Chaldea, the principle of weighing the good deeds over against the bad deeds is fully developed. “For three days after dissolution,” says Vaux, in his Nineveh and Persepolis, giving an account of Parsee doctrines in regard to the dead, “the soul is supposed to flit round its tenement of clay, in hopes of reunion; on the fourth, the Angel Seroch appears, and conducts it to the bridge of Chinevad. On this structure, which they assert connects heaven and earth, sits the Angel of Justice, to weigh the actions of mortals; when the good deeds prevail, the soul is met on the bridge by a dazzling figure, which says, ‘I am thy good angel, I was pure originally, but thy good deeds have rendered me purer’; and passing his hand over the neck of the blessed soul, leads it to Paradise. If iniquities preponderate, the soul is meet by a hideous spectre, which howls out, ‘I am thy evil genius; I was impure from the first, but thy misdeeds have made me fouler; through thee we shall remain miserable until the resurrection’; the sinning soul is then dragged away to hell, where Ahriman sits to taunt it with its crimes.” Such is the doctrine of Parseeism.

The same is the case in China, where Bishop Hurd, giving an account of the Chinese descriptions of the infernal regions, and of the figures that refer to them, says, “One of them always represents a sinner in a pair of scales, with his iniquities in the one, and his good works in another.” “We meet with several such representations,” he adds, “in the Grecian mythology.” Thus does Sir J. F. Davis describe the operation of the principle in China: “In a work of some note on morals, called Merits and Demerits Examined, a man is directed to keep a debtor and creditor account with himself of the acts of each day, and at the end of the year to wind it up. If the balance is in his favour, it serves as the foundation of a stock of merits for the ensuing year: and if against him, it must be liquidated by future good deeds. Various lists and comparative tables are given of both good and bad actions in the several relations of life; and benevolence is strongly inculcated in regard first to man, and, secondly, to the brute creation. To cause another’s death is reckoned at one hundred on the side of demerit; while a single act of charitable relief counts as one on the other side…To save a person’s life ranks in the above work as an exact set-off to the opposite act of taking it away; and it is said that this deed of merit will prolong a person’s life twelve years.”

While such a mode of justification is, on the one hand, in the very nature of the case, utterly demoralising, there never could by means of it, on the other, be in the bosom of any man whose conscience is aroused, any solid feeling of comfort, or assurance as to his prospects in the eternal world. Who could ever tell, however good he might suppose himself to be, whether the “sum of his good actions” would or would not counterbalance the amount of sins and transgressions that his conscience might charge against him. How very different the Scriptural, the god-like plan of “justification by faith,” and “faith alone, without the deeds of the law,” absolutely irrespective of human merits, simply and solely through the “righteousness of Christ, that is unto all and upon all them that believe,” that delivers at once and for ever “from all condemnation,” those who accept of the offered Saviour, and by faith are vitally united to Him. It is not the will of our Father in heaven, that His children in this world should be ever in doubt and darkness as to the vital point of their eternal salvation. Even a genuine saint, no doubt, may for a season, if need be, be in heaviness through manifold temptations, but such is not the natural, the normal state of a healthful Christian, of one who knows the fulness and the freeness of the blessings of the Gospel of peace. God has laid the most solid foundation for all His people to say, with John,

“We have KNOWN and believed the love which God hath to us” (1 John 4:16); .

or with Paul,

“I am PERSUADED that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor powers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature, shall be able to separate us from the love of God, which is in Christ Jesus” (Rom 8:38,39)

But this no man can every say, who “goes about to establish his own righteousness” (Rom 10:3), who seeks, in any shape, to be justified by works. Such assurance, such comfort, can come only from a simple and believing reliance on the free, unmerited grace of God, given in and alongwith Christ, the unspeakable gift of the Father’s love. It was this that made Luther’s spirit to be, as he himself declared, “as free as a flower of the field,” when, single and alone, he went up to the Diet of Worms, to confront all the prelates and potentates there convened to condemn the doctrine which he held. It was this that in every age made the martyrs go with such sublime heroism not only to prison but to death. It is this that emancipates the soul, restores the true dignity of humanity, and cuts up by the roots all the imposing pretensions of priestcraft. It is this only that can produce a life of loving, filial, hearty obedience to the law and commandments of God; and that, when nature fails, and when the king of terrors is at hand, can enable poor, guilty sons of men, with the deepest sense of unworthiness, yet to say,

“O death, where is thy sting? O grave, where is thy victory? Thanks be unto God, who giveth us the victory through Jesus Christ our Lord” (1 Cor 15:55,57).

Now, to all such confidence in God, such assurance of salvation, spiritual despotism in every age, both Pagan and Papal, has ever shown itself unfriendly. Its grand object has always been to keep the souls of its votaries away from direct and immediate intercourse with a living and merciful Saviour, and consequently from assurance of His favour, to inspire a sense of the necessity of human mediation, and so to establish itself on the ruins of the hopes and the happiness of the world. Considering the pretensions which the Papacy makes to absolute infallibility, and the supernatural powers which it attributes to the functions of its priests, in regard to regeneration and the forgiveness of sins, it might have been supposed, as a matter of course, that all its adherents would have been encouraged to rejoice in the continual assurance of their personal salvation. But the very contrary is the fact. After all its boastings and high pretensions, perpetual doubt on the subject of a man’s salvation, to his life’s end, is inculcated as a duty; it being peremptorily decreed as an article of faith by the Council of Trent, “That no man can know with infallible assurance of faith that he HAS OBTAINED the grace of God.” This very decree of Rome, while directly opposed to the Word of God, stamps its own lofty claims with the brand of imposture; for if no man who has been regenerated by its baptism, and who has received its absolution from sin, can yet have any certain assurance after all that “the grace of God” has been conferred upon him, what can be the worth of its opus operatum? Yet, in seeking to keep its devotees in continual doubt and uncertainty as to their final state, it is “wise after its generation.”

In the Pagan system, it was the priest alone who could at all pretend to anticipate the operation of the scales of Anubis; and, in the confessional, there was from time to time, after a sort, a mimic rehearsal of the dread weighing that was to take place at last in the judgment scene before the tribunal of Osiris. There the priest sat in judgment on the good deeds and bad deeds of his penitents; and, as his power and influence were founded to a large extent on the mere principle of slavish dread, he took care that the scale should generally turn in the wrong direction, that they might be more subservient to his will in casting in a due amount of good works into the opposite scale. As he was the grand judge of what these works should be, it was his interest to appoint what should be most for the selfish aggrandisement of himself, or the glory of his order; and yet so to weigh and counterweigh merits and demerits, that there should always be left a large balance to be settled, not only by the man himself, but by his heirs. If any man had been allowed to believe himself beforehand absolutely sure of glory, the priests might have been in danger of being robbed of their dues after death–an issue by all means to be guarded against. Now, the priests of Rome have in every respect copied after the priests of Anubis, the god of the scales. In the confessional, when they have an object to gain, they make the sins and transgressions good weight; and then, when they have a man of influence, or power, or wealth to deal with, they will not give him the slightest hope till round sums of money, or the founding of an abbey, or some other object on which they have set their heart, be cast into the other scale. In the famous letter of Pere La Chaise, the confessor of Louis XIV of France, giving an account of the method which he adopted to gain the consent of that licentious monarch to the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, by which such cruelties were inflicted on his innocent Huguenot subjects, we see how the fear of the scales of St. Michael operated in bringing about the desired result: “Many a time since,” says the accomplished Jesuit, referring to an atrocious sin of which the king had been guilty, “many a time since, when I have had him at confession, I have shook hell about his ears, and made him sigh, fear and tremble, before I would give him absolution. By this I saw that he had still an inclination to me, and was willing to be under my government; so I set the baseness of the action before him by telling the whole story, and how wicked it was, and that it could not be forgiven till he had done some good action to BALANCE that, and expiate the crime. Whereupon he at last asked me what he must do. I told him that he must root out all heretics from his kingdom.” This was the “good action” to be cast into the scale of St. Michael the Archangel, to “BALANCE” his crime. The king, wicked as he was–sore against his will-consented; the “good action” was cast in, the “heretics” were extirpated; and the king was absolved. But yet the absolution was not such but that, when he went the way of all the earth, there was still much to be cast in before the scales could be fairly adjusted. Thus Paganism and Popery alike

” make merchandise of the souls of men” (Rev 18:13).

Thus the one with the scales of Anubis, the other with the scales of St. Michael, exactly answer to the Divine description of Ephraim in his apostacy:

“Ephraim is a merchant, the balances of deceit are in his hand” (Hosea 12:7).

The Anubis of the Egyptians was precisely the same as the Mercury of the Greeks–the “god of thieves.” St. Michael, in the hands of Rome, answers exactly to the same character. By means of him and his scales, and their doctrine of human merits, they have made what they call the house of God to be nothing else than a “den of thieves.” To rob men of their money is bad, but infinitely worse to cheat them also of their souls.

Into the scales of Anubis, the ancient Pagans, by way of securing their justification, were required to put not merely good deeds, properly so called, but deeds of austerity and self-mortification inflicted on their own persons, for averting the wrath of the gods. The scales of St. Michael inflexibly required to be balanced in the very same way. The priests of Rome teach that when sin is forgiven, the punishment is not thereby fully taken away. However perfect may be the pardon that God, through the priests, may bestow, yet punishment, greater or less, still remains behind, which men must endure, and that to “satisfy the justice of God.” Again and again has it been shown that man cannot do anything to satisfy the justice of God, that to that justice he is hopelessly indebted, that he “has” absolutely “nothing to pay”; and more than that, that there is no need that he should attempt to pay one farthing; for that, in behalf of all who believe, Christ has finished transgression, made an end of sin, and made all the satisfaction to the broken law that that law could possibly demand. Still Rome insists that every man must be punished for his own sins, and that God cannot be satisfied * without groans and sighs, lacerations of the flesh, tortures of the body, and penances without number, on the part of the offender, however broken in heart, however contrite that offender may be.

* Bishop HAY’S Sincere Christian. The words of Bishop Hay are: “But He absolutely demands that, by penitential works, we PUNISH ourselves for our shocking ingratitude, and satisfy the Divine justice for the abuse of His mercy.” The established modes of “punishment,” as is well known, are just such as are described in the text.

Now, looking simply at the Scripture, this perverse demand for self-torture on the part of those for whom Christ has made a complete and perfect atonement, might seem exceedingly strange; but, looking at the real character of the god whom the Papacy has set up for the worship of its deluded devotees, there is nothing in the least strange about it. That god is Moloch, the god of barbarity and blood. Moloch signifies “king”; and Nimrod was the first after the flood that violated the patriarchal system, and set up as “king” over his fellows. At first he was worshipped as the “revealer of goodness and truth,” but by-and-by his worship was made to correspond with his dark and forbidding countenance and complexion. The name Moloch originally suggested nothing of cruelty or terror; but now the well known rites associated with that name have made it for ages a synonym for all that is most revolting to the heart of humanity, and amply justify the description of Milton (Paradise Lost):

“First Moloch, horrid king, besmeared with blood

Of human sacrifice, and parents’ tears,

Though, for the noise of drums and timbrels loud,

Their children’s cries unheard, that passed through fire

To his grim idol.”

In almost every land the bloody worship prevailed; “horrid cruelty,” hand in hand with abject superstition, filled not only “the dark places of the earth,” but also regions that boasted of their enlightenment. Greece, Rome, Egypt, Phoenicia, Assyria, and our own land under the savage Druids, at one period or other in their history, worshipped the same god and in the same way. Human victims were his most acceptable offerings; human groans and wailings were the sweetest music in his ears; human tortures were believed to delight his heart. His image bore, as the symbol of “majesty,” a whip, and with whips his worshippers, at some of his festivals, were required unmercifully to scourge themselves. “After the ceremonies of sacrifice,” says Herodotus, speaking of the feast of Isis at Busiris, “the whole assembly, to the amount of many thousands, scourge themselves; but in whose honour they do this I am not at liberty to disclose.” This reserve Herodotus generally uses, out of respect to his oath as an initiated man; but subsequent researches leave no doubt as to the god “in whose honour” the scourgings took place. In Pagan Rome the worshippers of Isis observed the same practice in honour of Osiris. In Greece, Apollo, the Delian god, who was identical with Osiris, * was propitiated with similar penances by the sailors who visited his shrine, as we learn from the following lines of Callimachus in his hymn to Delos:

“Soon as they reach thy soundings, down at once

They drop slack sails and all the naval gear.

The ship is moored; nor do the crew presume

To quit thy sacred limits, till they’ve passed

A fearful penance; with the galling whip

Lashed thrice around thine altar.”

* We have seen already, that the Egyptian Horus was just a new incarnation of Osiris or Nimrod. Now, Herodotus calls Horus by the name of Apollo. Diodorus Siculus, also, says that “Horus, the son of Isis, is interpreted to be Apollo.” Wilkinson seems, on one occasion, to call this identity of Horus and Apollo in question; but he elsewhere admits that the story of Apollo’s “combat with the serpent Pytho is evidently derived from the Egyptian mythology,” where the allusion is to the representation of Horus piercing the snake with a spear. From divers considerations, it may be shown that this conclusion is correct: 1. Horus, or Osiris, was the sun-god, so was Apollo. 2. Osiris, whom Horus represented, was the great Revealer; the Pythian Apollo was the god of oracles. 3. Osiris, in the character of Horus, was born when his mother was said to be persecuted by the malice of her enemies. Latona, the mother of Apollo, was a fugitive for a similar reason when Apollo was born. 4. Horus, according to one version of the myth, was said, like Osiris, to have been cut in pieces (PLUTARCH, De Iside). In the classic story of Greece, this part of the myth of Apollo was generally kept in the background; and he was represented as victor in the conflict with the serpent; but even there it was sometimes admitted that he had suffered a violent death, for by Porphyry he is said to have been slain by the serpent, and Pythagoras affirmed that he had seen his tomb at Tripos in Delphi (BRYANT). 5. Horus was the war-god. Apollo was represented in the same way as the great god represented in Layard, with the bow and arrow, who was evidently the Babylonian war-god, Apollo’s well known title of “Arcitenens,”–“the bearer of the bow,” having evidently been borrowed from that source. Fuss tells us that Apollo was regarded as the inventor of the art of shooting with the bow, which identifies him with Sagittarius, whose origin we have already seen. 6. Lastly, from Ovid (Metam.) we learn that, before engaging with Python, Apollo had used his arrows only on fallow-deer, stags, &c. All which sufficiently proves his substantial identification with the mighty Hunter of Babel.

Over and above the scourgings, there were also slashings and cuttings of the flesh required as propitiatory rites on the part of his worshippers. “In the solemn celebration of the Mysteries,” says Julius Firmicus, “all things in order had to be done, which the youth either did or suffered at his death.” Osiris was cut in pieces; therefore, to imitate his fate, so far as living men might do so, they were required to cut and wound their own bodies. Therefore, when the priests of Baal contended with Elijah, to gain the favour of their god, and induce him to work the desired miracle in their behalf, “they cried aloud and cut themselves, after their manner, with knives and with lancets, till the blood gushed out upon them” (1 Kings 18:28). In Egypt, the natives in general, though liberal in the use of the whip, seem to have been sparing of the knife; but even there, there were men also who mimicked on their own persons the dismemberment of Osiris. “The Carians of Egypt,” says Herodotus, in the place already quoted, “treat themselves at this solemnity with still more severity, for they cut themselves in the face with swords” (HERODOTUS). To this practice, there can be no doubt, there is a direct allusion in the command in the Mosaic law, “Ye shall make no cuttings in your flesh for the dead” (Lev 19:28). * These cuttings in the flesh are largely practised in the worship of the Hindoo divinities, as propitiatory rites or meritorious penances. They are well known to have been practised in the rites of Bellona, ** the “sister” or “wife of the Roman war-god Mars,” whose name, “The lamenter of Bel,” clearly proves the original of her husband to whom the Romans were so fond of tracing back their pedigree.

* Every person who died in the faith was believed to be identified with Osiris, and called by his name. (WILKINSON)

** “The priests of Bellona,” says Lactantius, “sacrificed not with any other men’s blood but their own, their shoulders being lanced, and with both hands brandishing naked swords, they ran and leaped up and down like mad men.”

They were practised also in the most savage form in the gladiatorial shows, in which the Roman people, with all their boasted civilisation, so much delighted. The miserable men who were doomed to engage in these bloody exhibitions did not do so generally of their own free will. But yet, the principle on which these shows were conducted was the very same as that which influenced the priests of Baal. They were celebrated as propitiatory sacrifices. From Fuss we learn that “gladiatorial shows were sacred” to Saturn; and in Ausonius we read that “the amphitheatre claims its gladiators for itself, when at the end of December they PROPITIATE with their blood the sickle-bearing Son of Heaven.” On this passage, Justus Lipsius, who quotes it, thus comments: “Where you will observe two things, both, that the gladiators fought on the Saturnalia, and that they did so for the purpose of appeasing and PROPITIATING Saturn.” “The reason of this,” he adds, “I should suppose to be, that Saturn is not among the celestial but the infernal gods. Plutarch, in his book of ‘Summaries,’ says that ‘the Romans looked upon Kronos as a subterranean and infernal God.'” There can be no doubt that this is so far true, for the name of Pluto is only a synonym for Saturn, “The Hidden One.” *

* The name Pluto is evidently from “Lut,” to hide, which with the Egyptian definite article prefixed, becomes “P’Lut.” The Greek “wealth,” “the hidden thing,” is obviously formed in the same way. Hades is just another synonym of the same name.

But yet, in the light of the real history of the historical Saturn, we find a more satisfactory reason for the barbarous custom that so much disgraced the escutcheon of Rome in all its glory, when mistress of the world, when such multitudes of men were “Butchered to make a Roman holiday.”

When it is remembered that Saturn himself was cut in pieces, it is easy to see how the idea would arise of offering a welcome sacrifice to him by setting men to cut one another in pieces on his birthday, by way of propitiating his favour.

The practice of such penances, then, on the part of those of the Pagans who cut and slashed themselves, was intended to propitiate and please their god, and so to lay up a stock of merit that might tell in their behalf in the scales of Anubis. In the Papacy, the penances are not only intended to answer the same end, but, to a large extent,they are identical. I do not know, indeed, that they use the knife as the priests of Baal did; but it is certain that they look upon the shedding of their own blood as a most meritorious penance, that gains them high favour with God, and wipes away many sins. Let the reader look at the pilgrims at Lough Dergh, in Ireland, crawling on their bare knees over the sharp rocks, and leaving the bloody tracks behind them, and say what substantial difference there is between that and cutting themselves with knives. In the matter of scourging themselves, however, the adherents of the Papacy have literally borrowed the lash of Osiris. Everyone has heard of the Flagellants, who publicly scourge themselves on the festivals of the Roman Church, and who are regarded as saints of the first water. In the early ages of Christianity such flagellations were regarded as purely and entirely Pagan. Athenagoras, one of the early Christian Apologists, holds up the Pagans to ridicule for thinking that sin could be atoned for, or God propitiated, by any such means. But now, in the high places of the Papal Church, such practices are regarded as the grand means of gaining the favour of God. On Good Friday, at Rome and Madrid, and other chief seats of Roman idolatry, multitudes flock together to witness the performances of the saintly whippers, who lash themselves till the blood gushes in streams from every part of their body. They pretend to do this in honour of Christ, on the festival set apart professedly to commemorate His death, just as the worshippers of Osiris did the same on the festival when they lamented for his loss. *

* The priests of Cybele at Rome observed the same practice.

But can any man of the least Christian enlightenment believe that the exalted Saviour can look on such rites as doing honour to Him, which pour contempt on His all-perfect atonement, and represent His most “precious blood” as needing to have its virtue supplemented by that of blood drawn from the backs of wretched and misguided sinners? Such offerings were altogether fit for the worship of Moloch; but they are the very opposite of being fit for the service of Christ.