The Two Babylons Chapter III. Festivals.

This is the continuation Chapter II. Objects of Worship

Section I.—Christmas and Lady-Day.

IF Rome be indeed the Babylon of the Apocalypse, and the Madonna enshrined in her sanctuaries be the very queen of heaven, for the worshiping of whom the fierce anger of God was provoked against the Jews in the days of Jeremiah, it is of the last consequence that the fact should be established beyond all possibility of doubt; for that being once established, every one who trembles at the Word of God must shudder at the very thought of giving such a system, either individually or nationally, the least countenance or support. Something has been said already that goes far to prove the identity of the Roman and Babylonian systems; but at every step the evidence becomes still more overwhelming. That which arises from comparing the different festivals is peculiarly so.

The festivals of Rome are innumerable; but five of the most important may be singled out for elucidation, viz., Christmas-day, Lady-day, Easter, the Nativity of St. John, and the Feast of the Assumption. Each and all of these can be proved to be Babylonian.

And first, as to the festival in honor of the birth of Christ, or Christmas. How comes it that that festival was connected with the 25th of December? There is not a word in the Scriptures about the precise day of his birth, or the time of the year when he was born. What is recorded there, implies that at what time soever His birth took place, it could not have been on the 25th of December. At the time that the angel announced his birth to the shepherds of Bethlehem, they were feeding their flocks by night in the open fields. Now, no doubt, the climate of Palestine is not so severe as the climate of this country; but even there, though the heat of the day is considerable, the cold of the night, from December to February, is very piercing, and it was not the custom for the shepherds of Judea to watch their flocks in the open fields later than about the end of October. It is in the last degree incredible, then, that the birth of Christ could have. taken place at the end of December. There is great unanimity among commentators on this point. Besides Barnes, Doddridge, Lightfoot, Joseph Scaliger, and Jennings, in his ‘Jewish Antiquities,’ who are all of opinion that December 25th could not be the right time of our‘Lord’s nativity.

The celebrated Joseph Mede pronounces a very decisive opinion to the same effect. After a long and careful disquisition on the subject, among other arguments he adduces the following:— “At the birth of Christ every woman and child was to go to be taxed at the city whereto they belonged, whither some had long journeys; but the middle of winter was not fitting for such a business, especially for women with child, and children, to travel in. Therefore, Christ could not be born in the depth of winter. Again, at the time of Christ’s birth, the shepherds lay abroad watching with their flocks in the night time; but this was not likely to be in the middle of winter. And if any shall think the winter wind was not so extreme in these parts, let him remember the words of Christ in the gospel, ‘Pray that your flight be not in the winter.’ If the winter was so bad a time to flee in, it seems no fit time for shepherds to lie in the fields in, and women and children to travel in.”

Indeed, it is admitted by the most learned and candid writers of all parties that the day of our Lord’s birth cannot be determined, and that within the Christian Church no such festival as Christmas was ever heard of till the third century; and that not till the fourth century was far advanced did it gain much observance. How, then, did the Romish Church fix on December the 25th as Christmas-day? Why, thus: Long before the fourth century, and long before the Christian era itself, a festival was celebrated among the heathen, at that precise time of the year, in honor of the birth of the son of the Babylonian queen of heaven; and it may fairly be presumed that, in order to conciliate the heathen, and to swell the number of the nominal adherents of Christianity, the same festival was adopted by the Roman Church, giving it only the name of Christ.

This tendency on the part of Christians to meet Paganism half-way was very early developed; and we find Tertullian, even in his day, about the year 230, bitterly lamenting the inconsistency of the disciples of Christ in this respect, and contrasting it with the strict fidelity of the Pagans to their own superstition. “By us,” says he, “who are strangers to Sabbaths, and new moons, and festivals, once acceptable to God, the Saturnalia, the feasts of January, the Brumalia, and Matronalia, are now frequented; gifts are carried to and fro, new year’s day presents are made with din, and sports and banquets are celebrated with uproar; oh, how much more faithful are the heathen to their religion, who take special care to adopt no solemnity from the Christians.”

Upright men strove to stem the tide, but in spite of all their efforts, the apostasy went on, till the Church, with the exception of a small remnant, was submerged under Pagan superstition. That Christmas was originally a Pagan festival, is beyond all doubt. The time of the year, and the ceremonies with which it is still celebrated, prove its origin.

In Egypt, the son of Isis, the Egyptian title for the queen of heaven, was born at this very time “about the time of the winter solstice.” The very name by which Christmas is popularly known among ourselves—Yule-day —proves at once its Pagan and Babylonian origin. “Yule” is the Chaldee name for an “infant” or “little child;” and as the 25th of December was called by our Pagan Anglo-Saxon ancestors, “Yule” day, or the “Child’s day,” and the night that preceded it, “Mother-night,” long before they came in contact with Christianity, that sufficiently proves its real character. Far and wide, in the realms of Paganism, was this birth-day observed. This festival has been commonly believed to have had only an astronomical character, referring simply to the completion of the sun’s yearly course, and the commencement of a new cycles. But there is indubitable evidence that the festival in question had a much higher reference than this—that it commemorated not merely the figurative birth-day of the sun in the renewal of its course, but the birth-day of the grand Deliverer.

Among the Sabeans of Arabia, who regarded the moon, and not the sun, as the visible symbol of the favorite object of their idolatry, the same period was observed as the birth festival. Thus we read in Stanley’s ‘Sabean Philosophy’ “On the 24th day of the tenth month,” that is December, according to our reckoning, “the Arabians celebrated the BIRTH-DAY OF THE LORD— that is, the Moon.” The Lord Moon was the great object of Arabian worship, and that Lord Moon, according to them, was born on the 24th of December, which clearly shows that the birth which they celebrated had no necessary connection with the course of the sun.

It is worthy of special note, too, that if Christmas-day among the ancient Saxons of this island, was observed to celebrate the birth of any Lord of the host of heaven, the case must have been precisely the same here as it was in Arabia. The Saxons, as is well known, regarded the Sun as a female divinity, and the Moon as a male. It must have been the birth-day of the Lord Moon, therefore, and not of the Sun, that was celebrated by them on the 25th of December, even as the birth-day of the same Lord Moon was observed by the Arabians on the 24th of December.

The name of the Lord Moon in the East seems to have been Meni, for this appears the most natural interpretation of the divine statement in Isaiah lxv. 11, “But ye are they that forsake my holy mountain, that prepare a table for Gad, and that furnish the drink-offering unto Meni.”+ There is reason to believe that Gad refers to the sun-god, and that Meni in like manner designates the moon-divinity.

+In the authorized version Gad is rendered “that troop,” and Meni, “that number;” but the most learned admit that this is incorrect, and that the words are proper names.

Meni, or Manai, signifies “The numberer;” and it is by the changes of the moon that the months are numbered:” Psalm civ. 19, “He appointed the moon for seasons: the sun knoweth the time of its going down.” The name of the “Man of the Moon,” or the god who presided over that luminary among the Saxons, was Mané, is given in the ‘Edda,’ and Mani, in the ‘Voluspa.’ That it was the birth of the “Lord Moon” that was celebrated among our ancestors at Christmas, we have remarkable evidence in the name that is still given in the lowlands of Scotland to the feast on the last day of the year, which seems to be a remnant of the old birth-festival, for the cakes then made are called Nur-cakes, or

Birth-cakes. That name is Hogmanay.

Now, “Hog-Manai” in Chaldee signifies “The feast of the Numberer;” in other words, The festival of Deus Lunus, or of the Man of the Moon. To show the connection between country and country, and the inveterate endurance of old customs, it is worthy of remark, that Jerome, commenting on the very words of Isaiah already quoted, about spreading “a table for Gad,” and “pouring out a drink-offering to Meni,” observes that it “was the custom so late as his time [in the fourth century], in all cities, especially in Egypt and at Alexandria, to set tables, and furnish them with various luxurious articles of food, and with goblets containing a mixture of new wine, on the last day of the month and the year, and that the people drew omens from them in respect to the fruitfulness of the year.”

The Egyptian year began at a different time from ours; but this is as near as possible (only substituting whiskey for wine), the way in which Hogmanay is still observed on the last day of the last month of our year in Scotland. I do not know that any omens are drawn from anything that takes place at that time, but everybody in the south of Scotland is personally cognizant of the fact, that, on Hogmanay, or the evening before New Year’s Day, among those who observe old customs, a table is spread, and that while buns and other dainties are provided by those who can afford them, oat cakes and cheese are brought forth among those who never see oat cakes but on this occasion, and that strong drink forms an essential article of the provision.

Even where the sun was the favorite object of worship, as in Babylon itself and elsewhere, at this festival he was worshiped not merely as the orb of day, but as God incarnate. It was an essential principle of the Babylonian system, that the Sun or Baal was the one only God. When,therefore, Tammuz was worshiped as God incarnate, that implied also that he was an incarnation of the Sun.

In the Hindu mythology, which is admitted to be essentially Babylonian, this comes out very distinctly. There, Surya, or the Sun, is represented as being incarnate, and born for the purpose of subduing the enemies of the gods, who, without such a birth, could not have been subdued.

It was no mere astronomic festival, then, that the Pagans celebrated at the winter solstice. That festival at Rome was called the feast of Saturn, and the mode in which it was celebrated there, showed whence it had been derived. The feast, as regulated by Caligula, lasted five days; loose reins were given to drunkenness and revelry, slaves had a temporary emancipation} and used all manner of freedoms with their masters. This was precisely the way in which, according to Berosus, the Drunken festival of the month Thebeth, answering to our December, in other words, the festival of Bacchus, was celebrated in Babylon. “It was the custom,” says he, “during the five days it lasted, for masters to be in subjection to their servants, and one of them ruled the house, clothed in a purple garment like a king”: This “purple robed” servant was called “Zoganes,” the “Man of sport and wantonness,” and answered exactly to the “Lord of Misrule,” that, in the dark ages, was chosen in all Popish countries to head the revels of Christmas.

The wassailling bowl (a hot drink made with wine, beer, or cider) of Christmas had its precise counterpart in the “Drunken festival” of Babylon; and many of the other observances still kept up among ourselves at Christmas, came from the very same quarter. The candles, in some parts of England, lighted on Christmas-eve, and used so long as the festive season lasts, were equally lighted by the Pagans on the eve of the festival of the Babylonian God, to do honor to him: for it was one of the distinguishing peculiarities of his worship to have lighted wax-candles on his altars.

The Christmas tree, now so common among us, was equally common in Pagan Rome and Pagan Egypt. In Egypt that tree was the palm-tree; in Rome it was the fir; the palm-tree denoting the Pagan Messiah, as Baal-Tamar, the fir referring to him as Baal-Berith. The mother of Adonis, the Sun-God and great mediatorial divinity, was mystically said to have been changed into a tree, and when in that state, to have brought forth her divine son. If the mother was a tree, the son must have been recognized as the “Man the branch.” And this entirely accounts for the putting of the Yule Log into the fire on Christmas Eve, and the appearance of the Christmas tree the next morning. As Zeroashta, “The seed of the woman,” which name also signified Ignigena, or “ born of the fire,” he has to enter the fire on “Mother-night,” that he may be born the next day out of it, as the “Branch of God,” or the Tree that brings all divine gifts to men. But Why, it may be asked, does he enter the fire under the symbol of a Log? To understand this, it must be remembered that the divine child born at the winter solstice was born as a new incarnation of the great god, (after that god had been cut in pieces), on purpose to revenge his death upon his murderers. Now the great god, off in the midst of his power and glory, was symbolized as a huge tree, stripped of all its branches, and cut down almost to the ground. But the great serpent, the symbol of the life-restoring AEsculapius, twists itself around the dead stock, (see fig. 27): and lo, at its side up sprouts a young tree—a tree of an entirely different kind, that is destined never to be cut down by hostile power,— even the palm-tree, the well-known symbol of victory.

The Christmas tree, as has been stated, was generally at Rome a different tree, even the fir; but the very same idea as was implied in the palm-tree, was implied in the Christmas fir; for that covertly symbolized the new-born god as Baal- -berith, “Lord of the Covenant,” and thus shadowed forth the perpetuity and everlasting nature of his power, now that, after having fallen before his enemies, he had risen triumphant over them all. Therefore, the 25th of December, the day that was observed at Rome as the day when the victorious god reappeared on earth, was held as the Natalis invicti solis, “The birth-day of the unconquered Sun.”

Now, the Yule Log is the dead stock of Nimrod, deified as the sun-god, but cut down by his enemies; the Christmas tree is Nimrod redivivus—the slain god come to life again. In the light reflected by the above statement on customs that still linger amongst us, the origin of which has been lost in the midst of hoar antiquity, let the reader look at the singular practice still kept up in the South on Christmas-eve, of kissing under the mistletoe bough. That mistletoe bough in the Druidic superstition, which, as we have seen, was derived from Babylon, was a representation of the Messiah, “The man the branch.” The mistletoe was regarded as a divine branch—a branch that came from heaven, and grew upon a tree that sprung out of the earth. Thus by the engrafting of the celestial branch into the earthly tree, heaven and earth, that sin had severed, were joined together, and thus the mistletoe bough became the token of divine reconciliation to man, the kiss being the well-known token of pardon and reconciliation.

Whence could such an idea have come? May it not have come from the eighty-fifth Psalm, ver. 10, 11, “ Mercy and truth are met together; righteousness and peace have KISSED each other. Truth shall spring out of the earth [in consequence of the coming of the promised Savior], and righteousness shall look down from heaven”? Certain it is that that Psalm was written soon after the Babylonish captivity; and as multitudes of the Jews, after that event, still remained in Babylon under the guidance of inspired men, such as Daniel, as a part of the divine word it must have been communicated to them, as well as to their kinsmen in Palestine. Babylon was, at that time, the center of the civilized world; and thus Paganism, corrupting the divine symbol as it ever has done, had opportunities of sending forth its debased counterfeit of the truth to all the ends of the earth, through the mysteries that were affiliated with the great central system in Babylon. Thus the very customs of Christmas still existent cast surprising light at once on the revelations of grace made to all the earth, and the efforts made by Satan and his emissaries to materialize, carnalize, and degrade them.

In many countries the boar was sacrificed to the god, for the injury a boar was fabled to have done him. According to one version of the story of the death of Adonis, or Tammuz, it was, as we have seen, in consequence of a wound from the tusk of a boar that he died. The Phrygian Attes, the beloved of Cybele, whose story was identified with that of Adonis, was fabled to have perished in like manner, by the tusk of a boar. Therefore, Diana, who, though commonly represented in popular myths only as the huntress Diana, was in reality the great Mother of the gods, has frequently the boar’s head as her accompaniment, in token not of any mere success in the chase, but of her triumph over the grand enemy of the idolatrous system, in which she occupied so conspicuous a place. According to Theocritus, Venus was reconciled to the boar that killed Adonis, because, when brought in chains before her, it pleaded so pathetically that it had not killed her husband of malice prepense (premeditated), but only through accident. But yet, in memory of the deed that the mystic boar had done, many a boar lost its head or was offered in sacrifice to the offended goddess. In Smith, Diana is represented with a boar’s head lying beside her, on the top of a heap of stones: and in the accompanying woodcut, (fig. 28),in which the Roman emperor Trajan is represented burning incense to the same goddess, the boar’s head forms a very prominent figure.

On Christmas-day the Continental Saxons offered a boar in sacrifice to the Sun to propitiate her for the loss of her beloved Adonis. In Rome a similar observance had evidently existed; for a boar formed the great article at the feast of Saturn, as appears from the following words of Martial:—

Hence the boar’s head is still a standing dish in England at the Christmas dinner, when the reason of it is long since forgotten. Yea, the “Christmas goose,” and “Yule cakes,” were essential articles in the worship of the Babylonian Messiah, as that worship was practiced both in Egypt and at Rome (fig. 29). Wilkinson, in reference to Egypt, shows that “the favorite offering” of Osiris was “a goose,” and moreover, that the “goose could not be eaten except in the depth of winter.” As to Rome, Juvenal says, “that Osiris, if offended, could be pacified only by a large goose and a thin cake.”

The Egyptian God Seb, with his symbol the goose; and the Sacred Goose on a stand, as offered in sacrifice.

In many countries, we have evidence of a sacred character attached to the goose. It is well known that the capitol of Rome was on one occasion saved when on the point of being surprised by the Gauls, in the dead of night, by the cackling of the geese sacred to Juno, kept in the temple of Jupiter.”

The accompanying woodcut (fig. 30) proves that the goose in Asia Minor was the symbol of Cupid, just as it was the symbol of Seb in Egypt. In India, the goose occupied a similar position; for in that land we read of the sacred “Brahmany goose,” or goose sacred to Brahma. Finally, the monuments of Babylon show that the goose possessed a like mystic character in Chaldea, and that it was offered in sacrifice there, as well as in Rome or Egypt, for there the priest is seen with the goose in the one hand, and his sacrificing knife in the other. There can be no doubt, then, that the Pagan festival at the winter solstice, in other words, Christmas, was held in honor of the birth of the Babylonian Messiah.

The consideration of the next great festival in the Popish calendar gives the very strongest confirmation to what has now been said. That festival, called Lady-day, is celebrated at Rome on the 25th of March, in alleged commemoration of the miraculous conception of our Lord in the womb of the Virgin, on the day when the angel was sent to announce to her the distinguished honor that was to be bestowed upon her, as the mother of the Messiah. But who could tell when this annunciation was made? The Scripture gives no clue at all in regard to the time. But it mattered not. Before our Lord was either conceived or born, that very day now set down in the Popish calendar for the “Annunciation of the Virgin,” was observed in Pagan Rome in honor of Cybele, the Mother of the Babylonian Messiah.

Now, it is manifest that Lady-day and Christmas-day stand in intimate relation to one another. Between the 25th of March and the 25th of December there are exactly nine months. If, then, the false Messiah was conceived in March and born in December, can any one for a moment believe that the conception and birth of the true Messiah can have so exactly synchronized, not only to the month, but to the day? The thing is incredible. Lady-day and Christmas-day, then, are purely Babylonian.

Section II — Easter

Then look at Easter. What means the term Easter itself? It is not a Christian name. It bears its Chaldean origin on its very forehead. Easter is nothing else than Astarte, one of the titles of Beltis, the queen of heaven, whose name, as pronounced by the people Nineveh, was evidently identical with that now in common use in this country. That name, as found by Layard on the Assyrian monuments, is Ishtar. The worship of Bel and Astarte was very early introduced into Britain, along with the Druids, “the priests of the groves.” Some have imagined that the Druidical worship was first introduced by the Phoenicians, who, centuries before the Christian era, traded to the tin-mines of Cornwall. But the unequivocal traces of that worship are found in regions of the British islands where the Phoenicians never penetrated, and it has everywhere left indelible marks of the strong hold which it must have had on the early British mind.

From Bel, the 1st of May is still called Beltane in the Almanac; and we have customs still lingering at this day among us, which prove how exactly the worship of Bel or Moloch (for both titles belonged to the same god) had been observed even in the northern parts of this island. “The late Lady Baird, of Fern Tower, in Perthshire,” says a writer in “Notes and Queries,” thoroughly versed in British antiquities, “told me, that every year, at Beltane (or the 1st of May), a number of men and women assemble at an ancient Druidical circle of stones on her property near Crieff. They light a fire in the centre, each person puts a bit of oat-cake in a shepherd’s bonnet; they all sit down, and draw blindfold a piece from the bonnet. One piece has been previously blackened, and whoever gets that piece has to jump through the fire in the centre of the circle, and pay a forfeit. This is, in fact, a part of the ancient worship of Baal, and the person on whom the lot fell was previously burnt as a sacrifice. Now, the passing through the fire represents that, and the payment of the forfeit redeems the victim.” If Baal was thus worshipped in Britain, it will not be difficult to believe that his consort Astarte was also adored by our ancestors, and that from Astarte, whose name in Nineveh was Ishtar, the religious solemnities of April, as now practised, are called by the name of Easter–that month, among our Pagan ancestors, having been called Easter-monath. The festival, of which we read in Church history, under the name of Easter, in the third or fourth centuries, was quite a different festival from that now observed in the Romish Church, and at that time was not known by any such name as Easter. It was called Pasch, or the Passover, and though not of Apostolic institution, * was very early observed by many professing Christians, in commemoration of the death and resurrection of Christ.

* Socrates, the ancient ecclesiastical historian, after a lengthened account of the different ways in which Easter was observed in different countries in his time–i.e., the fifth century–sums up in these words: “Thus much already laid down may seem a sufficient treatise to prove that the celebration of the feast of Easter began everywhere more of custom than by any commandment either of Christ or any Apostle.” (Hist. Ecclesiast.) Every one knows that the name “Easter,” used in our translation of Acts 12:4, refers not to any Christian festival, but to the Jewish Passover. This is one of the few places in our version where the translators show an undue bias.

That festival agreed originally with the time of the Jewish Passover, when Christ was crucified, a period which, in the days of Tertullian, at the end of the second century, was believed to have been the 23rd of March. That festival was not idolatrous, and it was preceded by no Lent. “It ought to be known,” said Cassianus, the monk of Marseilles, writing in the fifth century, and contrasting the primitive Church with the Church in his day, “that the observance of the forty days had no existence, so long as the perfection of that primitive Church remained inviolate.” Whence, then, came this observance? The forty days’ abstinence of Lent was directly borrowed from the worshippers of the Babylonian goddess. Such a Lent of forty days, “in the spring of the year,” is still observed by the Yezidis or Pagan Devil-worshippers of Koordistan, who have inherited it from their early masters, the Babylonians. Such a Lent of forty days was held in spring by the Pagan Mexicans, for thus we read in Humboldt, where he gives account of Mexican observances: “Three days after the vernal equinox…began a solemn fast of forty days in honour of the sun.” Such a Lent of forty days was observed in Egypt, as may be seen on consulting Wilkinson’s Egyptians. This Egyptian Lent of forty days, we are informed by Landseer, in his Sabean Researches, was held expressly in commemoration of Adonis or Osiris, the great mediatorial god. At the same time, the rape of Proserpine seems to have been commemorated, and in a similar manner; for Julius Firmicus informs us that, for “forty nights” the “wailing for Proserpine” continued; and from Arnobius we learn that the fast which the Pagans observed, called “Castus” or the “sacred” fast, was, by the Christians in his time, believed to have been primarily in imitation of the long fast of Ceres, when for many days she determinedly refused to eat on account of her “excess of sorrow,” that is, on account of the loss of her daughter Proserpine, when carried away by Pluto, the god of hell. As the stories of Bacchus, or Adonis and Proserpine, though originally distinct, were made to join on and fit in to one another, so that Bacchus was called Liber, and his wife Ariadne, Libera (which was one of the names of Proserpine), it is highly probable that the forty days’ fast of Lent was made in later times to have reference to both. Among the Pagans this Lent seems to have been an indispensable preliminary to the great annual festival in commemoration of the death and resurrection of Tammuz, which was celebrated by alternate weeping and rejoicing, and which, in many countries, was considerably later than the Christian festival, being observed in Palestine and Assyria in June, therefore called the “month of Tammuz”; in Egypt, about the middle of May, and in Britain, some time in April.

To conciliate the Pagans to nominal Christianity, Rome, pursuing its usual policy, took measures to get the Christian and Pagan festivals amalgamated, and, by a complicated but skilful adjustment of the calendar, it was found no difficult matter, in general, to get Paganism and Christianity–now far sunk in idolatry–in this as in so many other things, to shake hands. The instrument in accomplishing this amalgamation was the abbot Dionysius the Little, to whom also we owe it, as modern chronologers have demonstrated, that the date of the Christian era, or of the birth of Christ Himself, was moved FOUR YEARS from the true time. Whether this was done through ignorance or design may be matter of question; but there seems to be no doubt of the fact, that the birth of the Lord Jesus was made full four years later than the truth. This change of the calendar in regard to Easter was attended with momentous consequences. It brought into the Church the grossest corruption and the rankest superstition in connection with the abstinence of Lent. Let any one only read the atrocities that were commemorated during the “sacred fast” or Pagan Lent, as described by Arnobius and Clemens Alexandrinus, and surely he must blush for the Christianity of those who, with the full knowledge of all these abominations, “went down to Egypt for help” to stir up the languid devotion of the degenerate Church, and who could find no more excellent way to “revive” it, than by borrowing from so polluted a source; the absurdities and abominations connected with which the early Christian writers had held up to scorn. That Christians should ever think of introducing the Pagan abstinence of Lent was a sign of evil; it showed how low they had sunk, and it was also a cause of evil; it inevitably led to deeper degradation. Originally, even in Rome, Lent, with the preceding revelries of the Carnival, was entirely unknown; and even when fasting before the Christian Pasch was held to be necessary, it was by slow steps that, in this respect, it came to conform with the ritual of Paganism. What may have been the period of fasting in the Roman Church before sitting of the Nicene Council does not very clearly appear, but for a considerable period after that Council, we have distinct evidence that it did not exceed three weeks. *

* GIESELER, speaking of the Eastern Church in the second century, in regard to Paschal observances, says: “In it [the Paschal festival in commemoration of the death of Christ] they [the Eastern Christians] eat unleavened bread, probably like the Jews, eight days throughout…There is no trace of a yearly festival of a resurrection among them, for this was kept every Sunday” (Catholic Church). In regard to the Western Church, at a somewhat later period–the age of Constantine–fifteen days seems to have been observed to religious exercises in connection with the Christian Paschal feast, as appears from the following extracts from Bingham, kindly furnished to me by a friend, although the period of fasting is not stated. Bingham (Origin) says: “The solemnities of Pasch [are] the week before and the week after Easter Sunday–one week of the Cross, the other of the resurrection. The ancients speak of the Passion and Resurrection Pasch as a fifteen days’ solemnity. Fifteen days was enforced by law by the Empire, and commanded to the universal Church…Scaliger mentions a law of Constantine, ordering two weeks for Easter, and a vacation of all legal processes.”

The words of Socrates, writing on this very subject, about AD 450, are these: “Those who inhabit the princely city of Rome fast together before Easter three weeks, excepting the Saturday and Lord’s-day.” But at last, when the worship of Astarte was rising into the ascendant, steps were taken to get the whole Chaldean Lent of six weeks, or forty days, made imperative on all within the Roman empire of the West. The way was prepared for this by a Council held at Aurelia in the time of Hormisdas, Bishop of Rome, about the year 519, which decreed that Lent should be solemnly kept before Easter. It was with the view, no doubt, of carrying out this decree that the calendar was, a few days after, readjusted by Dionysius. This decree could not be carried out all at once. About the end of the sixth century, the first decisive attempt was made to enforce the observance of the new calendar. It was in Britain that the first attempt was made in this way; and here the attempt met with vigorous resistance. The difference, in point of time, betwixt the Christian Pasch, as observed in Britain by the native Christians, and the Pagan Easter enforced by Rome, at the time of its enforcement, was a whole month; * and it was only by violence and bloodshed, at last, that the Festival of the Anglo-Saxon or Chaldean goddess came to supersede that which had been held in honour of Christ.

* CUMMIANUS, quoted by Archbishop USSHER, Sylloge Those who have been brought up in the observance of Christmas and Easter, and who yet abhor from their hearts all Papal and Pagan idolatry alike, may perhaps feel as if there were something “untoward” in the revelations given above in regard to the origin of these festivals. But a moment’s reflection will suffice entirely to banish such a feeling. They will see, that if the account I have given be true, it is of no use to ignore it. A few of the facts stated in these pages are already known to Infidel and Socinian writers of no mean mark, both in this country and on the Continent, and these are using them in such a way as to undermine the faith of the young and uninformed in regard to the very vitals of the Christian faith. Surely, then, it must be of the last consequence, that the truth should be set forth in its own native light, even though it may somewhat run counter to preconceived opinions, especially when that truth, justly considered, tends so much at once to strengthen the rising youth against the seductions of Popery, and to confirm them in the faith once delivered to the Saints.

If a heathen could say, “Socrates I love, and Plato I love, but I love truth more,” surely a truly Christian mind will not display less magnanimity. Is there not much, even in the aspect of the times, that ought to prompt the earnest inquiry, if the occasion has not arisen, when efforts, and strenuous efforts, should be made to purge out of the National Establishment in the south those observances, and everything else that has flowed in upon it from Babylon’s golden cup? There are men of noble minds in the Church of Cranmer, Latimer, and Ridley, who love our Lord Jesus Christ in sincerity, who have felt the power of His blood, and known the comfort of His Spirit. Let them, in their closets, and on their knees, ask the question, at their God and at their own consciences, if they ought not to bestir themselves in right earnest, and labour with all their might till such a consummation be effected. Then, indeed, would England’s Church be the grand bulwark of the Reformation–then would her sons speak with her enemies in the gate–then would she appear in the face of all Christendom, “clear as the sun, fair as the moon, and terrible as an army with banners.” If, however, nothing effectual shall be done to stay the plague that is spreading in her, the result must be disastrous, not only to herself, but to the whole empire.

Such is the history of Easter. The popular observances that still attend the period of its celebration amply confirm the testimony of history as to its Babylonian character. The hot cross buns of Good Friday, and the dyed eggs of Pasch or Easter Sunday, figured in the Chaldean rites just as they do now. The “buns,” known too by that identical name, were used in the worship of the queen of heaven, the goddess Easter, as early as the days of Cecrops, the founder of Athens–that is, 1500 years before the Christian era. “One species of sacred bread,” says Bryant, “which used to be offered to the gods, was of great antiquity, and called Boun.” Diogenes Laertius, speaking of this offering being made by Empedocles, describes the chief ingredients of which it was composed, saying, “He offered one of the sacred cakes called Boun, which was made of fine flour and honey.” The prophet Jeremiah takes notice of this kind of offering when he says,

“The children gather wood, the fathers kindle the fire, and the women knead their dough, to make cakes to the queen of heaven.” *

* Jeremiah 7:18. It is from the very word here used by the prophet that the word “bun” seems to be derived. The Hebrew word, with the points, was pronounced Khavan, which in Greek became sometimes Kapan-os (PHOTIUS, Lexicon Syttoge); and, at other times, Khabon (NEANDER, in KITTO’S Biblical Cyclopoedia). The first shows how Khvan, pronounced as one syllable, would pass into the Latin panis, “bread,” and the second how, in like manner, Khvon would become Bon or Bun. It is not to be overlooked that our common English word Loa has passed through a similar process of formation. In Anglo-Saxon it was Hlaf.

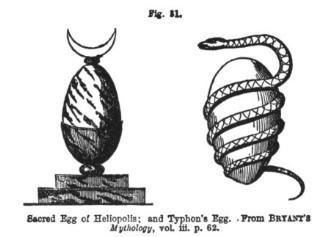

The hot cross buns are not now offered, but eaten, on the festival of Astarte; but this leaves no doubt as to whence they have been derived. The origin of the Pasch eggs is just as clear. The ancient Druids bore an egg, as the sacred emblem of their order. In the Dionysiaca, or mysteries of Bacchus, as celebrated in Athens, one part of the nocturnal ceremony consisted in the consecration of an egg. The Hindoo fables celebrate their mundane egg as of a golden colour. The people of Japan make their sacred egg to have been brazen. In China, at this hour, dyed or painted eggs are used on sacred festivals, even as in this country. In ancient times eggs were used in the religious rites of the Egyptians and the Greeks, and were hung up for mystic purposes in their temples. (see figure 31 below).

Figure 31

Figure 31

From Egypt these sacred eggs can be distinctly traced to the banks of the Euphrates. The classic poets are full of the fable of the mystic egg of the Babylonians; and thus its tale is told by Hyginus, the Egyptian, the learned keeper of the Palatine library at Rome, in the time of Augustus, who was skilled in all the wisdom of his native country: “An egg of wondrous size is said to have fallen from heaven into the river Euphrates. The fishes rolled it to the bank, where the doves having settled upon it, and hatched it, out came Venus, who afterwards was called the Syrian Goddess”–that is, Astarte. Hence the egg became one of the symbols of Astarte or Easter; and accordingly, in Cyprus, one of the chosen seats of the worship of Venus, or Astarte, the egg of wondrous size was represented on a grand scale. (see figure 32 below)

Figure 32

Figure 32

The occult meaning of this mystic egg of Astarte, in one of its aspects (for it had a twofold significance), had reference to the ark during the time of the flood, in which the whole human race were shut up, as the chick is enclosed in the egg before it is hatched. If any be inclined to ask, how could it ever enter the minds of men to employ such an extraordinary symbol for such a purpose, the answer is, first, The sacred egg of Paganism, as already indicated, is well known as the “mundane egg,” that is, the egg in which the world was shut up. Now the world has two distinct meanings–it means either the material earth, or the inhabitants of the earth. The latter meaning of the term is seen in Genesis 11:1, “The whole earth was of one language and of one speech,” where the meaning is that the whole people of the world were so. If then the world is seen shut up in an egg, and floating on the waters, it may not be difficult to believe, however the idea of the egg may have come, that the egg thus floating on the wide universal sea might be Noah’s family that contained the whole world in its bosom. Then the application of the word egg to the ark comes thus: The Hebrew name for an egg is Baitz, or in the feminine (for there are both genders), Baitza. This, in Chaldee and Phoenician, becomes Baith or Baitha, which in these languages is also the usual way in which the name of a house is pronounced. *

* The common word “Beth,” “house,” in the Bible without the points, is “Baith,” as may be seen in the name of Bethel, as given in Genesis 35:1, of the Greek Septuagint, where it is “Baith-el.”

The egg floating on the waters that contained the world, was the house floating on the waters of the deluge, with the elements of the new world in its bosom. The coming of the egg from heaven evidently refers to the preparation of the ark by express appointment of God; and the same thing seems clearly implied in the Egyptian story of the mundane egg which was said to have come out of the mouth of the great god. The doves resting on the egg need no explanation. This, then, was the meaning of the mystic egg in one aspect. As, however, everything that was good or beneficial to mankind was represented in the Chaldean mysteries, as in some way connected with the Babylonian goddess, so the greatest blessing to the human race, which the ark contained in its bosom, was held to be Astarte, who was the great civiliser and benefactor of the world. Though the deified queen, whom Astarte represented, had no actual existence till some centuries after the flood, yet through the doctrine of metempsychosis, which was firmly established in Babylon, it was easy for her worshippers to be made to believe that, in a previous incarnation, she had lived in the Antediluvian world, and passed in safety through the waters of the flood. Now the Romish Church adopted this mystic egg of Astarte, and consecrated it as a symbol of Christ’s resurrection. A form of prayer was even appointed to be used in connection with it, Pope Paul V teaching his superstitious votaries thus to pray at Easter: “Bless, O Lord, we beseech thee, this thy creature of eggs, that it may become a wholesome sustenance unto thy servants, eating it in remembrance of our Lord Jesus Christ, &c” (Scottish Guardian, April, 1844).

Besides the mystic egg, there was also another emblem of Easter, the goddess queen of Babylon, and that was the Rimmon or “pomegranate.” With the Rimmon or “pomegranate” in her hand, she is frequently represented in ancient medals, and the house of Rimmon, in which the King of Damascus, the Master of Naaman, the Syrian, worshipped, was in all likelihood a temple of Astarte, where that goddess with the Rimmon was publicly adored. The pomegranate is a fruit that is full of seeds; and on that account it has been supposed that it was employed as an emblem of that vessel in which the germs of the new creation were preserved, wherewith the world was to be sown anew with man and with beast, when the desolation of the deluge had passed away. But upon more searching inquiry, it turns out that the Rimmon or “pomegranate” had reference to an entirely different thing. Astarte, or Cybele, was called also Idaia Mater, and the sacred mount in Phrygia, most famed for the celebration of her mysteries, was named Mount Ida–that is, in Chaldee, the sacred language of these mysteries, the Mount of Knowledge. “Idaia Mater,” then, signifies “the Mother of Knowledge“–in other words, our Mother Eve, who first coveted the “knowledge of good and evil,” and actually purchased it at so dire a price to herself and to all her children. Astarte, as can be abundantly shown, was worshipped not only as an incarnation of the Spirit of God, but also of the mother of mankind. (see note below) When, therefore, the mother of the gods, and the mother of knowledge, was represented with the fruit of the pomegranate in her extended hand (see figure 33), inviting those who ascended the sacred mount to initiation in her mysteries, can there be a doubt what that fruit was intended to signify? Evidently, it must accord with her assumed character; it must be the fruit of the “Tree of Knowledge”–the fruit of that very

Besides the mystic egg, there was also another emblem of Easter, the goddess queen of Babylon, and that was the Rimmon or “pomegranate.” With the Rimmon or “pomegranate” in her hand, she is frequently represented in ancient medals, and the house of Rimmon, in which the King of Damascus, the Master of Naaman, the Syrian, worshipped, was in all likelihood a temple of Astarte, where that goddess with the Rimmon was publicly adored. The pomegranate is a fruit that is full of seeds; and on that account it has been supposed that it was employed as an emblem of that vessel in which the germs of the new creation were preserved, wherewith the world was to be sown anew with man and with beast, when the desolation of the deluge had passed away. But upon more searching inquiry, it turns out that the Rimmon or “pomegranate” had reference to an entirely different thing. Astarte, or Cybele, was called also Idaia Mater, and the sacred mount in Phrygia, most famed for the celebration of her mysteries, was named Mount Ida–that is, in Chaldee, the sacred language of these mysteries, the Mount of Knowledge. “Idaia Mater,” then, signifies “the Mother of Knowledge“–in other words, our Mother Eve, who first coveted the “knowledge of good and evil,” and actually purchased it at so dire a price to herself and to all her children. Astarte, as can be abundantly shown, was worshipped not only as an incarnation of the Spirit of God, but also of the mother of mankind. (see note below) When, therefore, the mother of the gods, and the mother of knowledge, was represented with the fruit of the pomegranate in her extended hand (see figure 33), inviting those who ascended the sacred mount to initiation in her mysteries, can there be a doubt what that fruit was intended to signify? Evidently, it must accord with her assumed character; it must be the fruit of the “Tree of Knowledge”–the fruit of that very

“Tree, whose mortal taste.

Brought death into the world, and all our woe.”

The knowledge to which the votaries of the Idaean goddess were admitted, was precisely of the same kind as that which Eve derived from the eating of the forbidden fruit, the practical knowledge of all that was morally evil and base. Yet to Astarte, in this character, men were taught to look at their grand benefactress, as gaining for them knowledge, and blessings connected with that knowledge, which otherwise they might in vain have sought from Him, who is the Father of lights, from whom cometh down every good and perfect gift. Popery inspires the same feeling in regard to the Romish queen of heaven, and leads its devotees to view the sin of Eve in much the same light as that in which Paganism regarded it. In the Canon of the Mass, the most solemn service in the Romish Missal, the following expression occurs, where the sin of our first parent is apostrophised: “Oh blessed fault, which didst procure such a Redeemer!” The idea contained in these words is purely Pagan. They just amount to this: “Thanks be to Eve, to whose sin we are indebted for the glorious Saviour.” It is true the idea contained in them is found in the same words in the writings of Augustine; but it is an idea utterly opposed to the spirit of the Gospel, which only makes sin the more exceeding sinful, from the consideration that it needed such a ransom to deliver from its awful curse. Augustine had imbibed many Pagan sentiments, and never got entirely delivered from them.

As Rome cherishes the same feelings as Paganism did, so it has adopted also the very same symbols, so far as it has the opportunity. In this country, and most of the countries of Europe, no pomegranates grow; and yet, even here, the superstition of the Rimmon must, as far as possible, be kept up. Instead of the pomegranate, therefore, the orange is employed; and so the Papists of Scotland join oranges with their eggs at Easter; and so also, when Bishop Gillis of Edinburgh went through the vain-glorious ceremony of washing the feet of twelve ragged Irishmen a few years ago at Easter, he concluded by presenting each of them with two eggs and an orange.

Now, this use of the orange as the representative of the fruit of Eden’s “dread probationary tree,” be it observed, is no modern invention; it goes back to the distant times of classic antiquity. The gardens of the Hesperides in the West, are admitted by all who have studied the subject, just to have been the counterpart of the paradise of Eden in the East. The description of the sacred gardens, as situated in the Isles of the Atlantic, over against the coast of Africa, shows that their legendary site exactly agrees with the Cape Verd or Canary Isles, or some of that group; and, of course, that the “golden fruit” on the sacred tree, so jealously guarded, was none other than the orange. Now, let the reader mark well: According to the classic Pagan story, there was no serpent in that garden of delight in the “islands of the blest,” to TEMPT mankind to violate their duty to their great benefactor, by eating of the sacred tree which he had reserved as the test of their allegiance. No; on the contrary, it was the Serpent, the symbol of the Devil, the Principle of evil, the Enemy of man, that prohibited them from eating the precious fruit–that strictly watched it–that would not allow it to be touched. Hercules, one form of the Pagan Messiah–not the primitive, but the Grecian Hercules–pitying man’s unhappy state, slew or subdued the serpent, the envious being that grudged mankind the use of that which was so necessary to make them at once perfectly happy and wise, and bestowed upon them what otherwise would have been hopelessly beyond their reach. Here, then, God and the devil are exactly made to change places. Jehovah, who prohibited man from eating of the tree of knowledge, is symbolised by the serpent, and held up as an ungenerous and malignant being, while he who emancipated man from Jehovah’s yoke, and gave him of the fruit of the forbidden tree–in other words, Satan under the name of Hercules–is celebrated as the good and gracious Deliverer of the human race. What a mystery of iniquity is here! Now all this is wrapped up in the sacred orange of Easter.

Notes

The Meaning of the Name Astarte

That Semiramis, under the name of Astarte, was worshipped not only as an incarnation of the Spirit of God, but as the mother of mankind, we have very clear and satisfactory evidence. There is no doubt that “the Syrian goddess” was Astarte (LAYARD’S Nineveh and its Remains). Now, the Assyrian goddess, or Astarte, is identified with Semiramis by Athenagoras (Legatio), and by Lucian (De Dea Syria). These testimonies in regard to Astarte, or the Syrian goddess, being, in one aspect, Semiramis, are quite decisive. 1. The name Astarte, as applied to her, has reference to her as being Rhea or Cybele, the tower-bearing goddess, the first as Ovid says (Opera), that “made (towers) in cities”; for we find from Layard that in the Syrian temple of Hierapolis, “she [Dea Syria or Astarte] was represented standing on a lion crowned with towers.” Now, no name could more exactly picture forth the character of Semiramis, as queen of Babylon, than the name of “Ash-tart,” for that just means “The woman that made towers.” It is admitted on all hands that the last syllable “tart” comes from the Hebrew verb “Tr.” It has been always taken for granted, however, that “Tr” signifies only “to go round.” But we have evidence that, in nouns derived from it, it also signifies “to be round,” “to surround,” or “encompass.” In the masculine, we find “Tor” used for “a border or row of jewels round the head” (see PARKHURST and also GESENIUS). And in the feminine, as given in Hesychius (Lexicon), we find the meaning much more decisively brought out. Turis is just the Greek form of Turit, the final t, according to the genius of the Greek language, being converted into s. Ash-turit, then, which is obviously the same as the Hebrew “Ashtoreth,” is just “The woman that made the encompassing wall.” Considering how commonly the glory of that achievement, as regards Babylon, was given to Semiramis, not only by Ovid, but by Justin, Dionysius, Afer, and others, both the name and mural crown on the head of that goddess were surely very appropriate.

In confirmation of this interpretation of the meaning of the name Astarte, I may adduce an epithet applied to the Greek Diana, who at Ephesus bore a turreted crown on her head, and was identified with Semiramis, which is not a little striking. It is contained in the following extract from Livy: “When the news of the battle [near Pydna] reached Amphipolis, the matrons ran together to the temple of Diana, whom they style Tauropolos, to implore her aid.” Tauropolos, from Tor, “a tower,” or “surrounding fortification,” and Pol, “to make,” plainly means the “tower-maker,” or “maker of surrounding fortifications”; and to her as the goddess of fortifications, they would naturally apply when they dreaded an attack upon their city.

Semiramis, being deified as Astarte, came to be raised to the highest honours; and her change into a dove, as has been already shown, was evidently intended, when the distinction of sex had been blasphemously attributed to the Godhead, to identify her, under the name of the Mother of the gods, with that Divine Spirit, without whose agency no one can be born a child of God, and whose emblem, in the symbolical language of Scripture, was the Dove, as that of the Messiah was the Lamb. Since the Spirit of God is the source of all wisdom, natural as well as spiritual, arts and inventions and skill of every kind being attributed to Him (Exo 31:3; 35:31), so the Mother of the gods, in whom that Spirit was feigned to be incarnate, was celebrated as the originator of some of the useful arts and sciences (DIODORUS SICULUS). Hence, also, the character attributed to the Grecian Minerva, whose name Athena, as we have seen reason to conclude, is only a synonym for Beltis, the well known name of the Assyrian goddess. Athena, the Minerva of Athens, is universally known as the “goddess of wisdom,” the inventress of arts and sciences. 2. The name Astarte signifies also the “Maker of investigations“; and in this respect was applicable to Cybele or Semiramis, as symbolised by the Dove. That this is one of the meanings of the name Astarte may be seen from comparing it with the cognate names Asterie and Astraea (in Greek Astraia), which are formed by taking the last member of the compound word in the masculine, instead of the feminine, Teri, or Tri (the latter being pronounced Trai or Trae), being the same in sense as Tart. Now, Asterie was the wife of Perseus, the Assyrian (HERODOTUS), and who was the founder of Mysteries (BRYANT). As Asterie was further represented as the daughter of Bel, this implies a position similar to that of Semiramis. Astraea, again, was the goddess of justice, who is identified with the heavenly virgin Themis, the name Themis signifying “the perfect one,” who gave oracles (OVID, Metam.), and who, having lived on earth before the Flood, forsook it just before that catastrophe came on. Themis and Astraea are sometimes distinguished and sometimes identified; but both have the same character as goddesses of justice. The explanation of the discrepancy obviously is, that the Spirit has sometimes been viewed as incarnate and sometimes not. When incarnate, Astraea is daughter of Themis. What name could more exactly agree with the character of a goddess of justice, than Ash-trai-a, “The maker of investigations,” and what name could more appropriately shadow forth one of the characters of that Divine Spirit, who “searcheth all things, yea, the deep things of God”? As Astraea, or Themis, was “Fatidica Themis,” “Themis the prophetic,” this also was another characteristic of the Spirit; for whence can any true oracle, or prophetic inspiration, come, but from the inspiring Spirit of God? Then, lastly, what can more exactly agree with the Divine statement in Genesis in regard to the Spirit of God, than the statement of Ovid, that Astraea was the last of the celestials who remained on earth, and that her forsaking it was the signal for the downpouring of the destroying deluge? The announcement of the coming Flood is in Scripture ushered in with these words (Gen 6:3):

“And the Lord said, My Spirit shall not always strive with man, for that he also is flesh: yet his days shall be an hundred and twenty years.“

All these 120 years, the Spirit was striving; when they came to an end, the Spirit strove no longer, forsook the earth, and left the world to its fate. But though the Spirit of God forsook the earth, it did not forsake the family of righteous Noah. It entered with the patriarch into the ark; and when that patriarch came forth from his long imprisonment, it came forth along with him. Thus the Pagans had an historical foundation for their myth of the dove resting on the symbol of the ark in the Babylonian waters, and the Syrian goddess, or Astarte–the same as Astraea–coming forth from it. Semiramis, then, as Astarte, worshipped as the dove, was regarded as the incarnation of the Spirit of God. 3. As Baal, Lord of Heaven, had his visible emblem, the sun, so she, as Beltis, Queen of Heaven, must have hers also–the moon, which in another sense was Asht-tart-e, “The maker of revolutions“; for there is no doubt that Tart very commonly signifies “going round.” But, 4th, the whole system must be dovetailed together.

As the mother of the gods was equally the mother of mankind, Semiramis, or Astarte, must also be identified with Eve; and the name Rhea, which, according to the Paschal Chronicle was given to her, sufficiently proves her identification with Eve. As applied to the common mother of the human race, the name Astarte is singularly appropriate; for, as she was Idaia mater, “The mother of knowledge,” the question is, “How did she come by that knowledge?” To this the answer can only be: “by the fatal investigations she made.” It was a tremendous experiment she made, when, in opposition to the Divine command, and in spite of the threatened penalty, she ventured to “search” into that forbidden knowledge which her Maker in his goodness had kept from her. Thus she took the lead in that unhappy course of which the Scripture speaks–“God made man upright, but they have SOUGHT out many inventions” (Eccl. 7:29).

Now Semiramis, deified as the Dove, was Astarte in the most gracious and benignant form. Lucius Ampelius calls her “the goddess benignant and merciful to me” (bringing them) “to a good and happy life.” In reference to this benignity of her character, both the titles, Aphrodite and Mylitta, are evidently attributed to her. The first I have elsewhere explained as “The wrath-subduer,” and the second is in exact accordance with it. Mylitta, or, as it is in Greek, Mulitta, signifies “The Mediatrix.” The Hebrew Melitz, which in Chaldee becomes Melitt, is evidently used in Job 33:23, in the sense of a Mediator; “the messenger, the interpreter” (Melitz), who is “gracious” to a man, and saith, “Deliver from going down to the pit: I have found a ransom,” being really “The Messenger, the MEDIATOR.” Parkhurst takes the word in this sense, and derives it from “Mltz,” “to be sweet.” Now, the feminine of Melitz is Melitza, from which comes Melissa, a “bee” (the sweetener, or producer of sweetness), and Melissa, a common name of the priestesses of Cybele, and as we may infer of Cybele, as Astarte, or Queen of Heaven, herself; for, after Porphyry, has stated that “the ancients called the priestesses of Demeter, Melissae,” he adds, that they also “called the Moon Melissa.” We have evidence, further, that goes far to identify this title as a title of Semiramis. Melissa or Melitta (APPOLODORUS)–for the name is given in both ways–is said to have been the mother of Phoroneus, the first that reigned, in whose days the dispersion of mankind occurred, divisions having come in among them, whereas before, all had been in harmony and spoke one language (Hyginus). There is no other to whom this can be applied but Nimrod; and as Nimrod came to be worshipped as Nin, the son of his own wife, the identification is exact. Melitta, then, the mother of Phoroneus, is the same as Mylitta, the well known name of the Babylonian Venus; and the name, as being the feminine of Melitz, the Mediator, consequently signifies the Mediatrix. Another name also given to the mother of Phoroneus, “the first that reigned,” is Archia (LEMPRIERE; SMITH). Now Archia signifies “Spiritual” (from “Rkh,” Heb. “Spirit,” which in Egyptian also is “Rkh” [BUNSEN]; and in Chaldee, with the prosthetic a prefixed becomes Arkh). * From the same root also evidently comes the epithet Architis, as applied to the Venus that wept for Adonis. Venus Architis is the spiritual Venus. **

* The Hebrew Dem, blood, in Chaldee becomes Adem; and, in like manner, Rkh becomes Arkh.

** From OUVAROFF we learn that the mother of the third Bacchus was Aura, and Phaethon is said by Orpheus to have been the son of the “wide extended air” (LACTANTIUS). The connection in the sacred language between the wind, the air, and the spirit, sufficiently accounts for these statements, and shows their real meaning.

Thus, then, the mother-wife of the first king that reigned was known as Archia and Melitta, in other words, as the woman in whom the “Spirit of God” was incarnate; and thus appeared as the “Dea Benigna,” “The Mediatrix” for sinful mortals. The first form of Astarte, as Eve, brought sin into the world; the second form before the Flood, was avenging as the goddess of justice. This form was “Benignant and Merciful.” Thus, also, Semiramis, or Astarte, as Venus the goddess of love and beauty, became “The HOPE of the whole world,” and men gladly had recourse to the “mediation” of one so tolerant of sin.

Section III — The Nativity of St. John

The Feast of the Nativity of St. John is set down in the Papal calendar for the 24th of June, or Midsummer-day. The very same period was equally memorable in the Babylonian calendar as that of one of its most celebrated festivals. It was at Midsummer, or the summer solstice, that the month called in Chaldea, Syria, and Phoenicia by the name of “Tammuz” began; and on the first day–that is, on or about the 24th of June–one of the grand original festivals of Tammuz was celebrated. *

* STANLEY’S Saboean Philosophy. In Egypt the month corresponding to Tammuz–viz., Epep–began June 25 (WILKINSON)

For different reasons, in different countries, other periods had been devoted to commemorate the death and reviving of the Babylonian god; but this, as may be inferred from the name of the month, appears to have been the real time when his festival was primitively observed in the land where idolatry had its birth. And so strong was the hold that this festival, with its peculiar rites, had taken of the minds of men, that even when other days were devoted to the great events connected with the Babylonian Messiah, as was the case in some parts of our own land, this sacred season could not be allowed to pass without the due observance of some, at least, of its peculiar rites. When the Papacy sent its emissaries over Europe, towards the end of the sixth century, to gather in the Pagans into its fold, this festival was found in high favour in many countries. What was to be done with it? Were they to wage war with it? No. This would have been contrary to the famous advice of Pope Gregory I, that, by all means they should meet the Pagans half-way, and so bring them into the Roman Church. The Gregorian policy was carefully observed; and so Midsummer-day, that had been hallowed by Paganism to the worship of Tammuz, was incorporated as a sacred Christian festival in the Roman calendar.

But still a question was to be determined, What was to be the name of this Pagan festival, when it was baptised, and admitted into the ritual of Roman Christianity? To call it by its old name of Bel or Tammuz, at the early period when it seems to have been adopted, would have been too bold. To call it by the name of Christ was difficult, inasmuch as there was nothing special in His history at that period to commemorate. But the subtlety of the agents of the Mystery of Iniquity was not to be baffled. If the name of Christ could not be conveniently tacked to it, what should hinder its being called by the name of His forerunner, John the Baptist? John the Baptist was born six months before our Lord. When, therefore, the Pagan festival of the winter solstice had once been consecrated as the birthday of the Saviour, it followed, as a matter of course, that if His forerunner was to have a festival at all, his festival must be at this very season; for between the 24th of June and the 25th of December–that is, between the summer and the winter solstice–there are just six months. Now, for the purposes of the Papacy, nothing could be more opportune than this. One of the many sacred names by which Tammuz or Nimrod was called, when he reappeared in the Mysteries, after being slain, was Oannes. *

* BEROSUS, BUNSEN’S Egypt. To identify Nimrod with Oannes, mentioned by Berosus as appearing out of the sea, it will be remembered that Nimrod has been proved to be Bacchus. Then, for proof that Nimrod or Bacchus, on being overcome by his enemies, was fabled to have taken refuge in the sea, see chapter 4, section i. When, therefore, he was represented as reappearing, it was natural that he should reappear in the very character of Oannes as a Fish-god. Now, Jerome calls Dagon, the well known Fish-god Piscem moeroris (BRYANT), “the fish of sorrow,” which goes far to identify that Fish-god with Bacchus, the “Lamented one”; and the identification is complete when Hesychius tells us that some called Bacchus Ichthys, or “The fish.”

The name of John the Baptist, on the other hand, in the sacred language adopted by the Roman Church, was Joannes. To make the festival of the 24th of June, then, suit Christians and Pagans alike, all that was needful was just to call it the festival of Joannes; and thus the Christians would suppose that they were honouring John the Baptist, while the Pagans were still worshipping their old god Oannes, or Tammuz. Thus, the very period at which the great summer festival of Tammuz was celebrated in ancient Babylon, is at this very hour observed in the Papal Church as the Feast of the Nativity of St. John. And the fete of St. John begins exactly as the festal day began in Chaldea. It is well known that, in the East, the day began in the evening. So, though the 24th be set down as the nativity, yet it is on St. John’s EVE–that is, on the evening of the 23rd–that the festivities and solemnities of that period begin.

Now, if we examine the festivities themselves, we shall see how purely Pagan they are, and how decisively they prove their real descent. The grand distinguishing solemnities of St. John’s Eve are the Midsummer fires. These are lighted in France, in Switzerland, in Roman Catholic Ireland, and in some of the Scottish isles of the West, where Popery still lingers. They are kindled throughout all the grounds of the adherents of Rome, and flaming brands are carried about their corn-fields. Thus does Bell, in his Wayside Pictures, describe the St. John’s fires of Brittany, in France: “Every fete is marked by distinct features peculiar to itself. That of St. John is perhaps, on the whole, the most striking. Throughout the day the poor children go about begging contributions for lighting the fires of Monsieur St. Jean, and towards evening one fire is gradually followed by two, three, four; then a thousand gleam out from the hill-tops, till the whole country glows under the conflagration. Sometimes the priests light the first fire in the market place; and sometimes it is lighted by an angel, who is made to descend by a mechanical device from the top of the church, with a flambeau in her hand, setting the pile in a blaze, and flying back again. The young people dance with a bewildering activity about the fires; for there is a superstition among them that, if they dance round nine fires before midnight, they will be married in the ensuing year. Seats are placed close to the flaming piles for the dead, whose spirits are supposed to come there for the melancholy pleasure of listening once more to their native songs, and contemplating the lively measures of their youth. Fragments of the torches on those occasions are preserved as spells against thunder and nervous diseases; and the crown of flowers which surmounted the principal fire is in such request as to produce tumultuous jealousy for its possession.” Thus is it in France.

Turn now to Ireland. “On that great festival of the Irish peasantry, St. John’s Eve,” says Charlotte Elizabeth, describing a particular festival which she had witnessed, “it is the custom, at sunset on that evening, to kindle immense fires throughout the country, built, like our bonfires, to a great height, the pile being composed of turf, bogwood, and such other combustible substances as they can gather. The turf yields a steady, substantial body of fire, the bogwood a most brilliant flame, and the effect of these great beacons blazing on every hill, sending up volumes of smoke from every point of the horizon, is very remarkable. Early in the evening the peasants began to assemble, all habited in their best array, glowing with health, every countenance full of that sparkling animation and excess of enjoyment that characterise the enthusiastic people of the land. I had never seen anything resembling it; and was exceedingly delighted with their handsome, intelligent, merry faces; the bold bearing of the men, and the playful but really modest deportment of the maidens; the vivacity of the aged people, and the wild glee of the children. The fire being kindled, a splendid blaze shot up; and for a while they stood contemplating it with faces strangely disfigured by the peculiar light first emitted when the bogwood was thrown on it. After a short pause, the ground was cleared in front of an old blind piper, the very beau ideal of energy, drollery, and shrewdness, who, seated on a low chair, with a well-plenished jug within his reach, screwed his pipes to the liveliest tunes, and the endless jig began. But something was to follow that puzzled me not a little. When the fire burned for some hours and got low, an indispensable part of the ceremony commenced. Every one present of the peasantry passed through it, and several children were thrown across the sparkling embers; while a wooden frame of some eight feet long, with a horse’s head fixed to one end, and a large white sheet thrown over it, concealing the wood and the man on whose head it was carried, made its appearance. This was greeted with loud shouts as the ‘white horse’; and having been safely carried, by the skill of its bearer, several times through the fire with a bold leap, it pursued the people, who ran screaming in every direction. I asked what the horse was meant for, and was told it represented ‘all cattle.’ Here,” adds the authoress, “was the old Pagan worship of Baal, if not of Moloch too, carried on openly and universally in the heart of a nominally Christian country, and by millions professing the Christian name! I was confounded, for I did not then know that Popery is only a crafty adaptation of Pagan idolatries to its own scheme.”

Such is the festival of St. John’s Eve, as celebrated at this day in France and in Popish Ireland. Such is the way in which the votaries of Rome pretend to commemorate the birth of him who came to prepare the way of the Lord, by turning away His ancient people from all their refuges of lies, and shutting them up to the necessity of embracing that kingdom of God that consists not in any mere external thing, but in “righteousness, and peace, and joy in the Holy Ghost.” We have seen that the very sight of the rites with which that festival is celebrated, led the authoress just quoted at once to the conclusion that what she saw before her was truly a relic of the Pagan worship of Baal.

The history of the festival, and the way in which it is observed, reflect mutual light upon each other. Before Christianity entered the British Isles, the Pagan festival of the 24th of June was celebrated among the Druids by blazing fires in honour of their great divinity, who, as we have already seen, was Baal. “These Midsummer fires and sacrifices,” says Toland, in his Account of the Druids, “were [intended] to obtain a blessing on the fruits of the earth, now becoming ready for gathering; as those of the first of May, that they might prosperously grow; and those of the last of October were a thanksgiving for finishing the harvest.” Again, speaking of the Druidical fires at Midsummer, he thus proceeds: “To return to our carn-fires, it was customary for the lord of the place, or his son, or some other person of distinction, to take the entrails of the sacrificed animals in his hands, and, walking barefoot over the coals thrice after the flames had ceased, to carry them straight to the Druid, who waited in a whole skin at the altar. If the nobleman escaped harmless, it was reckoned a good omen, welcomed with loud acclamations; but if he received any hurt, it was deemed unlucky both to the community and himself.” “Thus, I have seen,” adds Toland, “the people running and leaping through the St. John’s fires in Ireland; and not only proud of passing unsinged, but, as if it were some kind of lustration, thinking themselves in an especial manner blest by the ceremony, of whose original, nevertheless, they were wholly ignorant, in their imperfect imitation of it.”

We have seen reason already to conclude that Phoroneus, “the first of mortals that reigned”–i.e., Nimrod and the Roman goddess Feronia–bore a relation to one another. In connection with the firs of “St. John,” that relation is still further established by what has been handed down from antiquity in regard to these two divinities; and, at the same time, the origin of these fires is elucidated. Phoroneus is described in such a way as shows that he was known as having been connected with the origin of fire-worship. Thus does Pausanias refer to him: “Near this image [the image of Biton] they [the Argives] enkindle a fire, for they do not admit that fire was given by Prometheus, to men, but ascribe the invention of it to Phoroneus.” There must have been something tragic about the death of this fire-inventing Phoroneus, who “first gathered mankind into communities”; for, after describing the position of his sepulchre, Pausanias adds: “Indeed, even at present they perform funeral obsequies to Phoroneus”; language which shows that his death must have been celebrated in some such way as that of Bacchus. Then the character of the worship of Feronia, as coincident with fire-worship, is evident from the rites practised by the priests at the city lying at the foot of Mount Socracte, called by her name. “The priests,” says Bryant, referring both to Pliny and Strabo as his authorities, “with their feet naked, walked over a large quantity of live coals and cinders.” To this same practice we find Aruns in Virgil referring, when addressing Apollo, the sun-god, who had his shrine at Soracte, where Feronia was worshipped, and who therefore must have been the same as Jupiter Anxur, her contemplar divinity, who was regarded as a “youthful Jupiter,” even as Apollo was often called the “young Apollo”:

“O patron of Soracte’s high abodes,

Phoebus, the ruling power among the gods,

Whom first we serve; whole woods of unctuous pine

Are felled for thee, and to thy glory shine.

By thee protected, with our naked soles,

Through flames unsinged we march and tread the kindled coals.” *

* DRYDEN’S Virgil Aeneid. “The young Apollo,” when “born to introduce law and order among the Greeks,” was said to have made his appearance at Delphi “exactly in the middle of summer.” (MULLER’S Dorians)

Thus the St. John’s fires, over whose cinders old and young are made to pass, are traced up to “the first of mortals that reigned.”

It is remarkable, that a festival attended with all the essential rites of the fire-worship of Baal, is found among Pagan nations, in regions most remote from one another, about the very period of the month of Tammuz, when the Babylonian god was anciently celebrated. Among the Turks, the fast of Ramazan, which, says Hurd, begins on the 12th of June, is attended by an illumination of burning lamps. *

* HURD’S Rites and Ceremonies. The time here given by Hurd would not in itself be decisive as a proof of agreement with the period of the original festival of Tammuz; for a friend who has lived for three years in Constantinople informs me that, in consequence of the disagreement between the Turkish and the solar year, the fast of Ramazan ranges in succession through all the different months in the year. The fact of a yearly illumination in connection with religious observances, however, is undoubted.

In China where the Dragon-boat festival is celebrated in such a way as vividly to recall to those who have witnessed it, the weeping for Adonis, the solemnity begins at Midsummer. In Peru, during the reign of the Incas, the feast of Raymi, the most magnificent feast of the Peruvians, when the sacred fire every year used to be kindled anew from the sun, by means of a concave mirror of polished metal, took place at the very same period. Regularly as Midsummer came round, there was first, in token of mourning, “for three days, a general fast, and no fire was allowed to be lighted in their dwellings,” and then, on the fourth day, the mourning was turned into joy, when the Inca, and his court, followed by the whole population of Cuzco, assembled at early dawn in the great square to greet the rising of the sun. “Eagerly,” says Prescott, “they watched the coming of the deity, and no sooner did his first yellow rays strike the turrets and loftiest buildings of the capital, than a shout of gratulation broke forth from the assembled multitude, accompanied by songs of triumph, and the wild melody of barbaric instruments, that swelled louder and louder as his bright orb, rising above the mountain range towards the east, shone in full splendour on his votaries.” Could this alternate mourning and rejoicing, at the very time when the Babylonians mourned and rejoiced over Tammuz, be accidental? As Tammuz was the Sun-divinity incarnate, it is easy to see how such mourning and rejoicing should be connected with the worship of the sun.