The Two Babylons Chapter II. Objects of Worship

This is the continuation of the previous chapter, The Two Babylons I. Distinctive Character of the Two Systems.

Section I.—Trinity in Unity

IF there be this general coincidence between the systems of Babylon and Rome, the question arises, Does the coincidence stop here? To this the answer is, Far otherwise. We have only to bring the ancient Babylonian Mysteries to bear on the whole system of Rome, and then it will be seen how immensely the one is borrowed from the other. These Mysteries were long shrouded in darkness, but now the thick darkness begins to pass away. All who have paid the least attention to the literature Of Greece, Egypt, Phoenicia, or Rome, are aware of the place which the “Mysteries” occupied in these countries, and that, whatever circumstantial diversities there might be, in all essential respects these “Mysteries” in the different countries were the same.

Now, as the language of Jeremiah already quoted, would indicate that Babylon was the primal source from which all these systems of idolatry flowed, so the deductions of the most learned historians, on mere historical grounds, have led to the same conclusion. From Zonaras we find that the concurrent testimony Of the ancient authors he had consulted was to this effect; for speaking of arithmetic and astronomy, he says: “It is said that these came from the Chaldees to the Egyptians, and thence to the Greeks.” If the Egyptians and Greeks derived their arithmetic and astronomy from Chaldea, seeing these in Chaldea were sacred sciences, and monopolized by the priests, that is sufficient evidence that they must have derived their religion from the same quarter.

Both Bunsen and Layard in their researches have come substantially to the same result. The statement of Bunsen is to the effect that the religious system of Egypt was derived from Asia, and “the primitive empire in Babel.“ Layard, again, though taking a somewhat more favourable view of the system of the Chaldean MAGI than I am persuaded, the facts of history warrant, nevertheless thus speaks of that system:—“Of the great antiquity of this primitive worship there is abundant evidence, and that it originated among the inhabitants of the Assyrian plains, we have the united testimony of sacred and profane history. It obtained the epithet of perfect, and was believed to be the most ancient of religious systems, having preceded that of the Egyptians.

“The identity,” he adds, “of many of the Assyrian doctrines with those of Egypt is alluded to by Porphyry and Clemens;” and, in connection with the same subject, he quotes the following from Birch on Babylonian cylinders and monuments:——“ he zodiacal signs ….. show unequivocally that the Greeks derived their notions and arrangements of the zodiac [and consequently their Mythology, that was intertwined with it] from the Chaldees. The identity of Nimrod with the constellation Orion is not to be rejected.”

Ouvaroff, also, in his learned work on the Eleusinian mysteries, has come to the same conclusion. After referring to the fact that the Egyptian priests claimed the honor of having transmitted to the Greeks the first elements of Polytheism, he thus concludes:—“These positive facts would sufficiently prove, even without the conformity of ideas, that the Mysteries transplanted into Greece, and there united with a certain number of local notions, never lost the character of their origin derived from the cradle of the moral and religious ideas of the universe. All these separate facts—all these scattered testimonies, recur to that fruitful principle which places in the East the center of science and civilization.”

If thus we have evidence that Egypt and Greece derived their religion from Babylon, we have equal evidence that the religious system of the Phoenicians came from the same source. Macrobius shows that the distinguishing feature of the Phoenician idolatry must have been imported from Assyria, which in classic writers, included Babylonia. “The worship of the Architic Venus,” says he, “formerly flourished as much among the Assyrians as it does now among the Phoenicians.”

Now, to establish the identity between the systems of ancient Babylon and Papal Rome, we have just to inquire in how far does the system of the Papacy agree with the system established in these Babylonian Mysteries. In prosecuting such an inquiry there are considerable difficulties to be overcome; for, as in geology, it is impossible at all points to reach the deep, underlying strata of the earth’s surface, so it is not to be expected that in any one country we should find a complete and connected account of the system established in that country. But yet, even as the geologist, by examining the contents of a fissure here, an upheaval there, and what “crops out” of itself on the surface elsewhere, is enabled to determine, with wonderful certainty, the order and general contents of the different strata over all the earth, so it is with the subject of the Chaldean Mysteries. What is wanted in one country is supplemented in another; and what actually “crops out” in different directions, to a large extent necessarily determines the character of much that does not directly appear on the surface.

Taking, then, the admitted unity and Babylonian character of the ancient Mysteries of Egypt, Greece, Phoenicia, and Rome, as the clue to guide us in our researches, let us go on from step to step in our comparison of the doctrine and practice of the two Babylons—the Babylon of the Old Testament, and the Babylon of the New.

And here I have to notice, first, the identity of the objects of worship in Babylon and Rome. The ancient Babylonians, just as the modern Romans, recognized in words the unity of the Godhead; and, while worshiping innumerable minor deities, as possessed of certain influence on human affairs, they distinctly acknowledged that there was ONE infinite and Almighty Creator, supreme over all. Most other nations did the same. “In the early ages of mankind,” says Wilkinson in his “Ancient Egyptians,” “the existence of a sole and omnipotent Deity, who created all things, seems to have been the universal belief: and tradition taught men the same notions on this subject, which, in later times, have been adopted by all civilized nations.”

“The Gothic religion,” says Mallet, “taught the being of a supreme God, Master of the Universe, to whom all things were submissive and obedient.”—(Tacit. de Morib. Germ.) The ancient Icelandic mythology calls him “the Author of every thing that existeth, the eternal, the living, and awful Being; the searcher into concealed things, the Being that never changeth.” It attributeth to this deity “an infinite power, a boundless knowledge, and incorruptible justice.”

We have evidence of the same having been the faith of ancient Hindostan. Though modern Hinduism recognizes millions of gods, yet the Indian sacred books show that originally it had been far otherwise. Major Moor, speaking of Brahm, the supreme God of the Hindus, says:—“Of Him whose glory is so great, there is no image.” (Veda) He “illumines all, delights all, whence all proceeded; that by which they live when born, and that to which all must return.” (Veda.)

In the “Institutes of Menu,” he is characterized as “He whom the mind alone can perceive; whose essence eludes the external organs, who has no visible parts, who exists from eternity . . . . the soul of all beings, whom no being can comprehend.” In these passages, there is a trace of the existence of Pantheism; but the very language employed bears testimony to the existence among the Hindus at one period of a far purer faith.

Nay, not merely had the ancient Hindus exalted ideas of the natural perfections of God, but there is evidence that they were all aware of the gracious character of God, as revealed in his dealings with a lost and guilty world. This is manifest from the very name Brahm, appropriated by them to the one infinite and eternal God.

There has been a great deal of unsatisfactory speculation in regard to the meaning of this name, but when the different statements in regard to Brahm are carefully considered, it becomes evident that the name Brahm is just the Hebrew Rahm, with the digamma prefixed, which is very frequent in Sanskrit words derived from Hebrew or Chaldee. Rahm in Hebrew signifies “The merciful or compassionate one.” But Rahm also signifies the WOMB or the bowels as the seat of compassion.

Now we find such language applied to Brahm, the one supreme God, as cannot be accounted for, except on the supposition that Brahm had the very same meaning as the Hebrew Rahm. Thus, we find the god Krishna, in one of the Hindu sacred books, when asserting his high dignity as a divinity and his identity with the Supreme, using the following words: “The great Brahm is my WOMB, and in it I place my fetus, and from it is the procreation of all nature. The great Brahm is the WOMB of all the various forms which are conceived in every natural WOMB.” How could such language ever have been applied to “The supreme Brahm, the most holy, the most high God, the Divine being, before all other gods; Without birth, the mighty Lord, God of gods, the universal Lord,” but from the connection between Rahm “the womb,” and Rahm “the merciful one?” Here, then, we find that Brahm is just the same as “Er-Rahman,” “The all-merciful one,”— a title applied by the Turks to the Most High, and that the Hindus, notwithstanding their deep religious degradation now, had once known that “the most holy, most high God,” is also “the God of Mercy,” in other words, that he is “a just God and a Saviour.“

And proceeding on this interpretation of the name Brahm, we see how exactly their religious knowledge as to the creation had coincided with the account of the origin of all things, as given in Genesis. It is well known that the Brahmans, to exalt themselves as a priestly half-divine caste, to whom all others ought to bow down, have for many ages taught that, while the other castes came from the arms, and body, and feet of Brahma—the visible representative and manifestation of the invisible Brahm, and identified with him —they alone came from the mouth of the creative God.

Now we find statements in their sacred books which prove that once a very different doctrine must have been taught. Thus, in one of the Vedas, speaking of Brahma, it is expressly stated that “ALL beings” “ are created from his MOUTH.” In the passage in question an attempt is made to mystify the matter; but, taken in connection with the meaning of the name Brahm, as already given, who can doubt what was the real meaning of the statement, opposed though it be to the lofty and exclusive pretensions of the Brahmans? It evidently meant that He who, ever since the fall, has been revealed to man as the “Merciful: and Gracious One” (Exod. xxxiv. 6), was known at the same time as the Almighty One, who in the beginning “spake and it was done,” “ commanded and all things stood fast,” who made all things by the “Word of his power.”

After what has now been said, any one who consults the “Asiatic Researches,” vol. vii., p. 293, may see that it is in a great measure from a wicked perversion of this divine title of the One Living and True God, a title that ought to have been so dear to sinful men, that all those moral abominations have come that make the symbols of the pagan temples of India so offensive to the eye of purity.

So utterly idolatrous was the Babylonian recognition of the Divine unity, that Jehovah, the Living God, severely condemned his own people for giving any countenance to it: “They that sanctify themselves, and purify themselves in the gardens, after the rites of the ONLY ONE, eating swine’s flesh, and the abomination, and the mouse, shall be consumed together” (Isaiah lxvi. 17). In the unity of that only one God of the Babylonians, there were three persons, and to symbolize that doctrine of the Trinity, they employed, as the discoveries of Layard prove, the equilateral triangle, just as it is well known the Romish Church does at this day. In both cases such a comparison is most degrading to the King Eternal, and is fitted utterly to pervert the minds of those who contemplate it, as if there was or could be any similitude between such a figure and Him who hath said, “To whom will ye liken God, and what likeness will ye compare unto him?”

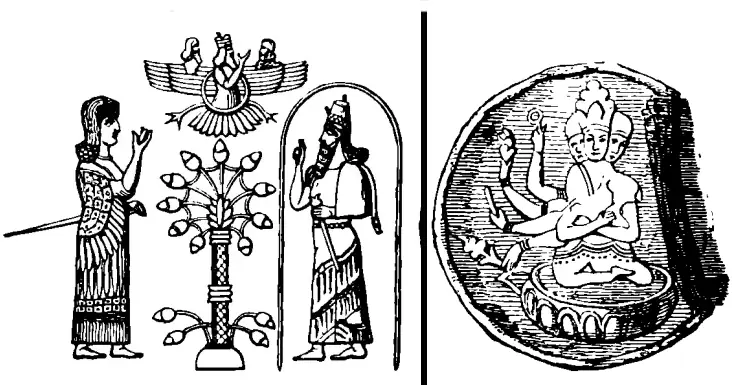

The Papacy has in some of its churches, as for instance, in the monastery of the so—called Trinitarians of Madrid, an image of the Triune God, with three heads on one body. The Babylonians had something of the same. Mr Layard, in his last work, has given a specimen of such a triune divinity, worshiped in ancient Assyria. (Fig. 3.)

The accompanying cut (fig. 4) of such another divinity, worshiped among the Pagans of Siberia, is taken from a medal in the Imperial Cabinet of St. Petersburg, and given in Parsons’ “Japhet.” The three heads are differently arranged in Layard’s specimen, but both alike are evidently intended to symbolize the same great truth, although all such representations of the Trinity necessarily and utterly debase the conceptions of those, among whom such images prevail, in regard to that sublime mystery of our faith. In India, the supreme divinity, in like manner, in one of the most ancient cave-temples, is represented with three heads on one body, under the name of “ Eko Deva Trimurtti,” “ One God, three forms.”

In Japan, the Buddhists worship their great divinity Buddha, with three heads, in the very same form, under the name of “San Pao Fuh.” All these have existed from ancient times. While overlaid with idolatry, the recognition of a Trinity was universal in all the ancient nations of the world, proving how deep-rooted in the human race was the primeval doctrine on this subject, which comes out so distinctly in Genesis.

When we look at the symbols in the triune figure of Layard, already referred to, and minutely examine them, they are very instructive. Layard regards the circle in that figure as signifying “Time without bounds.” But the hieroglyphic meaning of the circle is evidently different. A circle in Chaldee was Zero; and Zero also signified “the seed” Therefore, according to the genius of the mystic system of Chaldea, which was to a large extent founded on double meanings, that which, to the eyes of men in general, was only zero, “ a circle,” was understood by the initiated to signify zero, “the seed.”

Now, viewed in this light, the triune emblem of the supreme Assyrian divinity shows clearly what had been the original patriarchal faith. First, there is the head of the old man; next, there is the zero, or circle, for “the seed ;” and, lastly, the wings and tail of the bird or dove; showing, though blasphemously, the unity of Father, Seed, or Son, and Holy Ghost. While this had been the original way in which Pagan idolatry had represented the Triune God, and though this kind of representation had survived to Sennacherib’s time, yet there is evidence that, at a very early period, an important change had taken place in the Babylonian notions in regard to the divinity; and that the three persons had come to be, the eternal Father, the Spirit of God incarnate in a human mother, and a divine Son, the fruit of that incarnation.

Section II.—The Mother and Child. Sub-Section I – The Child in Assyria

While this was the theory, the first person in the Godhead was practically overlooked. As the Great Invisible, taking no immediate concern in human affairs, he was “to be worshiped through silence alone,” that is, in point of fact, he was not worshiped by the multitude at all. The same thing is strikingly illustrated in India at this day. Though Brahma, according, to the sacred books, is the first person of the Hindu Triad, and the religion of Hindustan is called by his name, yet he is never worshiped, and there is scarcely a single temple in all India now in existence of those that were formerly erected to his honor.

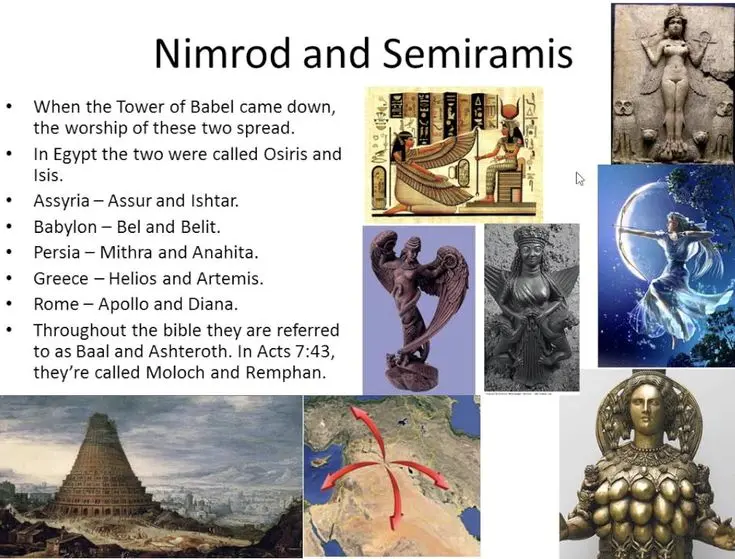

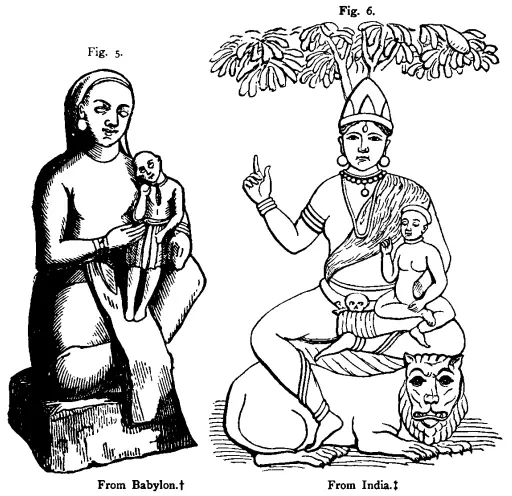

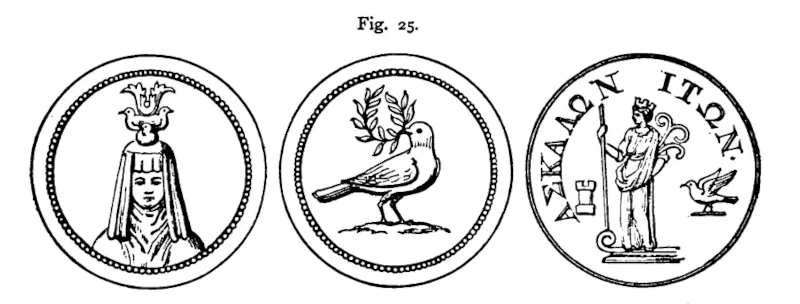

So also is it in those countries of Europe where the Papal system is most completely developed. In Papal Italy, as travelers universally admit (except where the gospel has recently entered), all appearance of worshiping the King Eternal and Invisible is almost extinct, while the Mother and the Child are the grand objects of worship. Exactly so, in this latter respect, also was it in Ancient Babylon. The Babylonians, in their popular religion, supremely worshiped a Goddess Mother and a Son, who was represented in pictures and in images as an infant or child in his mother’s arms (figs. 5 and 6). From Babylon this worship of the Mother and the Child spread to the ends of the earth. In Egypt the Mother and the Child were worshiped under the names of Isis and Osiris. In India, even to this day, as Isi and Iswara; in Asia, as Cybele and Deoius; in Pagan Rome, as Fortuna and Jupiter—puer, or, Jupiter, the boy; in Greece, as Ceres, the great Mother, with the babe at her breast, or as Irene, the goddess of Peace, with the boy Plntus in her arms; and even in Tibet, in China, in Japan, the Jesuit missionaries were astonished to find the counterpart of Madonna and her child as devoutly worshiped as in Papal Rome itself; Shing Moo, the Holy Mother in China, being represented with a child in her arms, and a glory around her, exactly as if a Roman Catholic artist had been employed to set her up.

Sub-Section I.—The Child In Assyria.

The original of that mother, so widely worshiped, there is reason to believe, was Semiramis, already referred to, who, it is well known, was worshiped by the Babylonians, and other eastern nations, and that under the name of Rhea, the great “Goddess Mother.”

It was from the son, however, that she derived all her glory and her claims to deification. That son, though represented as a child in his mother’s arms, was a person of great stature and immense bodily powers, as well as most fascinating manners. In Scripture he is referred to (Ezek. viii. 14:) under the name of Tammuz, but he is commonly known among classical writers under the name of Bacchus, that is,“ The Lamented one.” To the ordinary reader the name of Bacchus suggests nothing more than revelry and drunkenness; but it is now well known, that amid all the abominations that attended his orgies, their grand design was professedly “the purification of souls,” and that from the guilt and defilement of sin.

This lamented one, exhibited and adored as a little child in his mother’s arms, seems, in point of fact, to have been the husband of Semiramis, whose name, Ninus, by which he is commonly known in classical history, literally signified “The Son.” As Semiramis, the wife, was worshiped as Rhea, whose grand distinguishing character was that of the great goddess “Mother,” the conjunction with her of her husband, under the name of Ninus, or “The Son,” was sufficient to originate the peculiar worship of the “Mother and Son,” so extensively diffused among the nations of antiquity; and this, no doubt, is the explanation of the fact which has so much puzzled the inquirers into ancient history, that Ninus is sometimes called the husband, and sometimes the son of Semiramis. This also accounts for the origin of the very same confusion of relationship between Isis and Osiris, the mother and child of the Egyptians; for, as Bunsen shows, Osiris was represented in Egypt as at once the son and husband of his mother; and actually bore, as one of his titles of dignity and honor, the name “Husband of the Mother.” This still further casts light on the fact already noticed, that the Indian god Iswara is represented as a babe at the breast of his own wife Isi, or Parvati.

Now, this Ninus, or “Son,” borne in the arms of the Babylonian Madonna, is so described as very clearly to identify him with Nimrod. “ Ninus, king of the Assyrians,” says Trogus Pompeius, epitomized by Justin, “first of all changed the contented moderation of the ancient manners, incited by a new passion, the desire of conquest. He was the first who carried on war against his neighbors, and he conquered all nations from Assyria to Lybia, as they were yet unacquainted with the arts of war.” This account points directly to Nimrod, and can apply to no other.

The account of Diodorus Siculus entirely agrees with it, and adds another trait that goes still further to determine the identity. That account is as follows:— “Ninus, the most ancient of the Assyrian kings mentioned in history, performed great actions. Being naturally of a warlike disposition, and ambitious of glory that results from valor, he armed a considerable number of young men that were brave and vigorous like himself, trained them up a long time in laborious exercises and hardships, and by that means accustomed them to bear the fatigues of war, and to face dangers with intrepidity.” As Diodorus makes Ninus “the most ancient of the Assyrian kings,” and represents him as beginning those wars which raised his power to an extraordinary height by bringing the people of Babylonia under subjection to him, while as yet the city of Babylon was not in existence, this shows that be occupied the very position of Nimrod, of whom the scriptural account is, that he first “began to be mighty on the earth,” and that the “beginning of his kingdom was Babylon.” As the Babal builders, when their speech was confounded, were scattered abroad on the face of the earth, and therefore deserted both the city and the tower which they had commenced to build, Babylon, as a city, could not properly be said to exist till Nimrod, by establishing his power there, made it the foundation and starting-point of his greatness. In this respect, then, the story Of Ninus and of Nimrod exactly harmonize. The way, too, in which Ninus gained his power is the very way in which Nimrod erected his. There can be no doubt that it was by inuring his followers to the toils and dangers Of the chase, that he gradually formed them to the use of arms, and so prepared them for aiding him in establishing his dominion; just as Ninus, by training his companions for a long time “in laborious exercises and hardships,” qualified them for making him the first of the Assyrian kings.

The conclusions deduced from these testimonies of ancient history are greatly strengthened by many additional considerations. In Gen. x. 11, we find a passage, which, when its meaning is properly understood, casts a very steady light on the subject. That passage, as given in the authorized version, runs thus:—“Out of that land went forth Asshur, and builded Nineveh.” This speaks of it as something remarkable, that Asshur went out Of the land Of Shinar, while yet the human race in general went forth from the same land. It goes upon the supposition that Ashur had some sort Of divine right to that land, and that he had been, in a manner, expelled from it by Nimrod, while no divine right is elsewhere hinted at in the context, or seems capable of proof. Moreover, it represents Asshur as setting up IN THE IMMEDIATE NEIGHBORHOOD of Nimrod as mighty a kingdom as Nimrod himself, Asshur building four cities, one of which is emphatically said to have been “great” (ver. 12); ’while Nimrod, on this interpretation, built just the same number of cities, of which none is specially characterized as “great.”

Now, it is in the last degree improbable that Nimrod would have quietly borne so mighty a rival so near him To obviate such difficulties as these, it has been proposed to render the words, “out of that land he (Nimrod) went forth into Asshur, or Assyria.” But then, according to ordinary usage of grammar, the word in the original should have been “Ashurah,” with the sign of motion to a place affixed to it, whereas it is simply Asshur, without any such sign of motion affixed. I am persuaded that the whole perplexity that commentators have hitherto felt in considering this passage, has arisen from supposing that there is a proper name in the passage, where in reality no proper name exists. Ashur is the passive participle of a verb, which, in its Chaldee sense, signifies “to make strong,” and, consequently, signifies “being strengthened,” or “made strong.” Read thus, the whole passage is natural and easy, (ver. 10), “And the beginning of his (Nimrod’s) kingdom was Babel, and Erech, and Accad, and Calneh.” A beginning naturally implies something to succeed, and here we find it; (ver. 11), “Out of that land he went forth, being made strong, or when he had been made strong (asshur), and builded Nineveh,” etc.

Now, this exactly agrees with the statement in the ancient history of Justin: “Ninus strengthened the greatness of his acquired dominion by continued possession. Having subdued, therefore, his neighbors, when, by an accession of forces, being still further strengthened, he went forth against other tribes, and every new victory paved the way for another, he subdued all the peoples of the East“ Thus, then, Nimrod, or Ninus, was the builder of Nineveh; and the origin of the name of that city, as “the habitation of Ninus,” is accounted for, and light is thereby, at the same time, cast on the fact, that the name of the chief part of the ruins of Nineveh is Nimrod at this day.

Now, assuming that Ninus is Nimrod, the way in which that assumption explains what is otherwise inexplicable in the statements of ancient history greatly confirms the truth of that assumption itself. Ninus is said to have been the son of Belus or Bel, and Bel is said to have been the founder of Babylon. If Ninus was in reality the first king of Babylon, how could Belus or Bel, his father, be said to be the founder of it? Both might very well be, as will appear if we consider who was Bel, and what we can trace of his doings. If Ninus was Nimrod, who was the historical Bel? He must have been Cush; for “Cush begat Nimrod,” (Gen. x. 8); and Cush is generally represented as having been a ringleader in the great apostacy. But, again, Cush, as the son of Ham, was Her-mes or Mercury; for Hermes is just an Egyptian synonym for the “son of Ham.” Now, Hermes was the great original prophet of idolatry; for he was recognized by the pagans as the author of their religious rites, and the interpreter of the gods. The distinguished Gesenius identifies him with the Babylonian Nebo, as the prophetic god; and a statement of Hyginus shows that he was known as the grand agent in that movement which produced the division of tongues.

His words are these: “For many ages men lived under the government of Jove [evidently not the Roman Jupiter, but the Jehovah of the Hebrews], without cities and without laws, and all speaking one language. But after that Mercury interpreted the speeches of men (whence an interpreter is called Hermeneutes), the same individual distributed the nations. Then discord began.“

Here there is a manifest enigma. How could Mercury or Hermes have any need to interpret the speeches of mankind when they “all spake one language”? To find out the meaning of this, we must go to the language of the mysteries. Peresh, in Chaldee, signifies “to interpret;” but was pronounced by old Egyptians and by Greeks, and often by the Chaldees themselves, in the same way as “Peres,” to “divide.” Mercury, then, or Hermes, or Cush, “the son of Ham,” was the “DIVIDER of the speeches of men.” He, it would seem, had been the ringleader in the scheme for building the great city and tower of Babel, and, as the well-known title of Hermes,—“the interpreter of the gods,” would indicate, had encouraged them, in the name of God, to proceed in their presumptuous enterprise, and so had caused the language of men to be divided, and themselves to be scattered abroad on the face of the earth.

Now look at the name of Belus, or Bel, given to the father of Ninus, or Nimrod, in connection with this. While the Greek name Belus represented both the Baal and Bel of the Chaldees, these were nevertheless two entirely distinct titles. These titles were both alike often given to the same god, but they had totally different meanings. Baal, as we have already seen, signified “The Lord;” but Bel signified “The Confounder.” When, then, we read that Belus, the father of Ninus, was he that built or founded Babylon, can there be a doubt in what sense it was that the title of Belus was given to him? It must have been in the sense of Bel the “Confounder.” And to this meaning of the name of the Babylonian Bel, there is a very distinct allusion in Jeremiah l. 2, where it is said “Bel is confounded,” that is, “The Confounder is brought to confusion.”

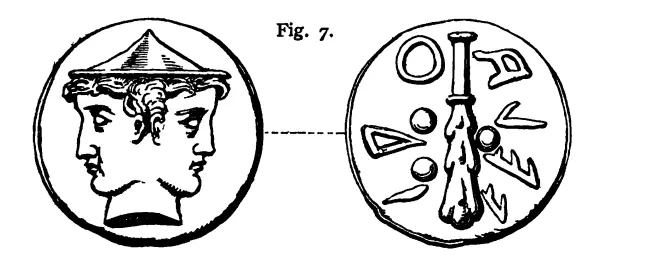

That Cush was known to Pagan antiquity under the very character of Bel “The Confounder,” a statement of Ovid very clearly proves. The statement to which I refer is that in which Janus “the god of gods,” from whom all the other gods had their origin, is made to say of himself: “The ancients . . . called me Chaos.” Now, first this decisively shows that Chaos was known not merely as a state of confusion, but as the “god of Confusion.” But, secondly, who that is at all acquainted with the laws of Chaldaic pronunciation, does not know that Chaos is just one of the established forms of the name of Chus or Cush? Then, look at the symbol of Janus (see fig.7), whom “the ancients called Chaos,” and it will be seen how exactly it tallies with the doings of Cush, when he is identified with Bel, “The Confounder.”

That symbol is a club; and the name of “a club” in Chaldee comes from the very word which signifies “to break in pieces, or scatter abroad.” He who caused the confusion of tongues was he who “broke” the previously united earth (Gen. xi. 1) “in pieces,” and “scattered” the fragments abroad. How significant, then, as a symbol, is the club, as commemorating the work of Cush, as Bel, the “Confounder”? And that significance will be all the more apparent when the reader turns to the Hebrew of Gen. xi. 9, and finds that the very word from which a club derives its name is that which is employed when it is said, that in consequence of the confusion of tongues, the children of men were “scattered abroad on the face of all the earth”: The word there used for scattering abroad is Hephaitz, which, in the Greek form becomes Hephaizt, and hence the origin of the well-known but little understood name of Hephaistos, as applied to Vulcan, “The father of the gods.” Hephaistos is the name of the ringleader in the first rebellion, as “The Scatterer abroad,” as Bel is the name of the same individual as the “Confounder of tongues.”

Here, then, the reader may see the real origin of Vulcan’s Hammer, which is just another name for the club of Janus or Chaos, “The god of Confusion;” and to this, as breaking the earth in pieces, there is a covert allusion in Jer. 50:23, where Babylon, as identified with its primeval god, is thus apostrophized: “How is the hammer of the whole-earth cut asunder and broken!”

Now, as the tower-building was the first act of open rebellion after the flood, and Cush, as Bel, was the ringleader in it, he was, of course, the first to whom the name Merodach, “The great Rebel,” must have been given, and, therefore, according to the usual parallelism of the prophetic language, we find both names of the Babylonian god referred to together, when the judgment on Babylon is predicted: “Bel is confounded: Merodach is broken to pieces,” (Jer. 50:2). The judgment comes upon the Babylonian god according to what he had done. As Bel, he had “confounded” the whole earth, therefore he is “confounded.” As Merodach, by the rebellion he had stirred up, he had “broken” the united world to pieces; therefore he himself is “broken to pieces.”

So much for the historical character of Bel, as identified with Janus or Chaos, the god of confusion, with his symbolical club. Proceeding, then, on these deductions, it is not difficult to see how it might be said that Bel or Belus, the father of Ninus, founded Babylon, while nevertheless Ninus or Nimrod was properly the builder of it. Now, though Bel or Cush, as being specially concerned in laying the first foundations of Babylon, might be looked upon as the first king, as in some of the copies of “Eusebius’s Chronicle” he is represented, yet it is evident, from both sacred history and profane, that he could never have reigned as king of the Babylonian monarchy, properly so called; and accordingly, in the Armenian version of the “Chronicle of Eusebius,” which bears the undisputed palm for correctness and authority, his name is entirely omitted in the list of Assyrian kings, and that of Ninus stands first, in such terms as exactly correspond with the scriptural account of Nimrod. Thus, then, looking at the fact that Ninus is currently made by antiquity the son of Belus, or Bel, when we have seen that the historical Bel is Cush, the identity of Ninus and Nimrod is still further confirmed.

But when we look at what is said of Semiramis, the wife of Ninus, the evidence receives an additional development. That evidence goes conclusively to show that the wife of Ninus could be none other than the wife of Nimrod, and, further, to bring out one of the grand characters in which Nimrod, when deified, was adored.

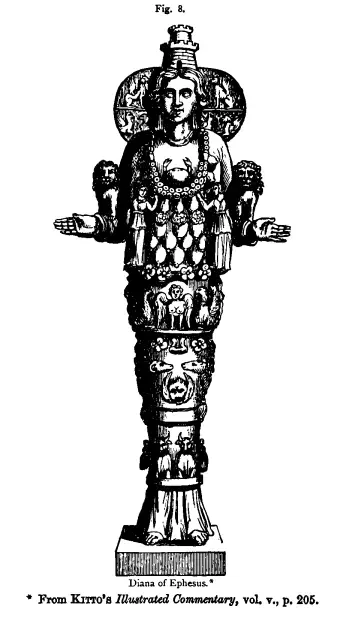

In Daniel xi. 38, we read of a god called Ala mahozim, i.e., the “god of fortifications.” Who this god of fortifications could be, commentators have found themselves at a loss to determine. In the records of antiquity the existence of any god of fortifications has been commonly overlooked; and it must he confessed that no such god stands forth there with any prominence to the ordinary reader. But of the existence of a goddess of fortifications, every one knows that there is the amplest evidence. That goddess is Cybele, who is universally represented with a mural or turreted crown, or with a fortification, on her head. Why was Rhea or Cybele thus represented? Ovid asks the question and answers it himself; and the answer is this: The reason, he says, why the statue of Cybele wore a crown of towers was, “because she first erected them in cities.” The first city in the world after the flood (from whence the commencement of the world itself was often dated) that had towers and encompassing walls, was Babylon; and Ovid himself tells us that it was Semiramis, the first queen of that city, who was believed to have “surrounded Babylon with a wall of brick.”

Semiramis, then, the first deified queen of that city and tower whose top was intended to reach to heaven, must have been the prototype of the goddess who “first made towers in cities.” When we look at the Ephesian Diana we find evidence to the very same effect. In general, Diana was depicted as a Virgin, and the patroness of virginity; but the Ephesian Diana was quite different. She was represented with all the attributes of the Mother of the gods (see fig. 8), and, as the Mother of the gods, she wore a turreted crown, such as no one can contemplate without being forcibly reminded of the tower of Babel. Now, this tower-bearing Diana is by an ancient scholiast expressly identified with Semiramis. When, therefore, we remember that Rhea, or Cybele, the tower-bearing goddess, was, in point of fact, a Babylonian goddess, and that Semiramis, when deified, was worshiped under the name of Rhea, there will remain, I think, no doubt as to the personal identity of the “goddess of fortifications.”

Now there is no reason to believe that Semiramis alone (though some have represented the matter so) built the battlements of Babylon. We have the express testimony of the ancient historian, Megasthenes, as preserved by Abydenus, that it was “Belus” who “surrounded Babylon with a wall.” As “Bel the Confounder,” who began the city and tower of Babel, had to leave both unfinished, this could not refer to him. It could refer only to his son Ninus, who inherited his father’s title, and who was the first actual king of the Babylonian empire, and, consequently, Nimrod.

The real reason that Semiramis, the wife of Ninus, gained the glory of finishing the fortifications of Babylon, was, that she came in the esteem of the ancient idolaters to hold a preponderating position, and to have attributed to her all the different characters that belonged, or were supposed to belong, to her husband. Having ascertained, then, one of the characters in which the deified wife was worshiped, we may from that conclude what was the corresponding character of the deified husband. Layard distinctly indicates his belief that Rhea or Cybele, the “tower-crowned” goddess, was just the female counterpart of the “deity presiding over bulwarks or fortresses;” and that this deity was Ninus, or Nimrod, we have still further evidence from what the scattered notices of antiquity say of the first deified king of Babylon, under a name that identifies him as the husband of Rhea, the “tower-bearing” goddess. That name is Kronos or Saturn. It is well known that Kronos, or Saturn, was Rhea’s husband; but it is not so well known who was Kronos himself. Traced back to his original, that divinity is proved to have been the first king of Babylon.

Theophilus of Antioch shows that Kronos in the cast was worshiped under the names of Bel and Bal; and from Eusebius we learn that the first of the Assyrian kings, whose name was Belus, was also by the Assyrians called Kronos. As the genuine copies of Eusebius do not admit of any Belus, as an actual king of Assyria, prior to Ninus, king of the Babylonians, and distinct from him, that shows that Ninus, the first king of Babylon, was Kronos. But, further, we find that Kronos was king of the Cyclops, who were his brethren, and who derived that name from him, and that the Cyclops were known as “the inventors of tower-building.”|| The king of the Cyclops, “the inventors of tower-building,” occupied a position exactly correspondent to that of Rhea, who “first erected (towers) in cities.” If, therefore, Rhea, the wife of Kronos, was the goddess of fortifications, Kronos or Saturn, the husband of Rhea, that is, Ninus or Nimrod, the first king of Babylon, must have been Ala mahozim, “the god of fortifications.”

The name Kronos itself goes not a little to confirm the argument. Kronos signifies “The Horned one.” As a horn is a well-known Oriental emblem for power or might, Kronos, “The Horned one,” was, according to the mystic system, just a synonym for the scriptural epithet applied to Nimrod, viz., Gheber, “ The mighty one.” (Gen. x. 8), “He began to be mighty on the earth.”

The name Kronos, as the classical reader is well aware, is applied to Saturn as the “Father of the gods.” We have already had another “father of the gods” brought under our notice, even Cush in his character of Bel the Confounder, or Hephaistos, “The Scatterer abroad;” and it is easy to understand how, when the deification of mortals began, and the “mighty” Son of Cush was deified, the father, especially considering the part which he seems to have had in concocting the whole idolatrous system, would have to be deified too, and of course, in his character as the Father of the “Mighty one,” and of all the “immortals ” that succeeded him. But, in point of fact, we shall find, in the course of our inquiry, that Nimrod was the actual Father of the gods, as being the first of deified mortals; and that, therefore, it is in exact accordance with historical fact that Kronos, the Horned, or Mighty one, is, in the Classic Pantheon, known by that title.

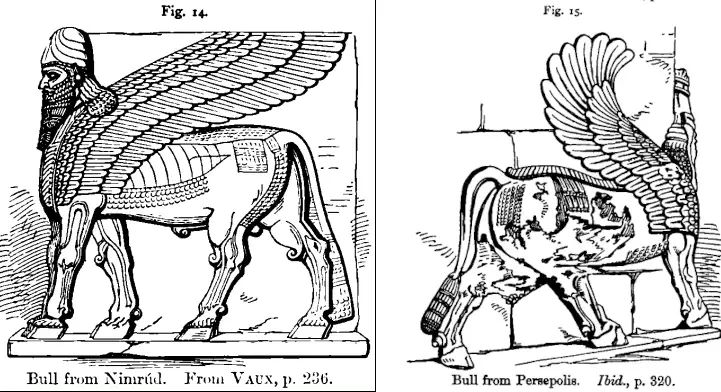

The meaning of this name Kronos, “The Horned one,” as applied to Nimrod, fully explains the origin of the remarkable symbol, so frequently occurring among the Nineveh sculptures, the gigantic HORNED man-bull, as representing the great divinities in Assyria. The same word that signified a bull, signified also a ruler or prince. Hence the “Horned bull” signified “The mighty Prince,” thereby pointing back to the first of those “Mighty ones,” who, under the name of Guebres, Gabrs, or Cabiri, occupied so conspicuous a place in the ancient world, and to whom the deified Assyrian monarchs covertly traced back the origin of their greatness and might.

This explains the reason why the Bacchus of the Greeks was represented as wearing horns, and why he was frequently addressed by the epithet “Bull-horned,” as one of the high titles of his dignity. Even in comparatively recent times, Togrul Begh, the leader of the Seljukian Turks, who came from the neighborhood of the Euphrates, was in a similar manner represented with three horns growing out of his head as the emblem of his sovereignty. (Fig. 9)

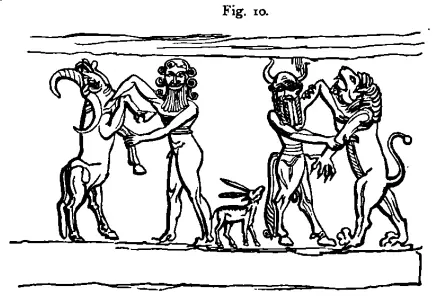

This, also, in a remarkable way accounts for the origin of one of the divinities worshiped by our Pagan Anglo-Saxon ancestors under the name of Zernebogus. This Zemebogus was “the black, malevolent, ill-omened divinity,” in other words, the exact counterpart of the popular idea of the Devil, as supposed to be black, and equipped with horns and hoofs. This name, analyzed and compared with the accompanying wood-cut (fig. 10), from Layard, casts a very singular light on the source from whence has come the popular superstition in regard to the grand Adversary.

The name Zer-Nebo-Gus is almost pure Chaldee, and seems to unfold itself as denoting “The seed of the prophet Cush.” We have seen reason already to conclude, that under the name Bel, as distinguished from Baal, Cush was the great soothsayer or false prophet worshiped at Babylon. But independent inquirers have been led to the conclusion, that Bel and Nebo were just two different titles for the same god, and that a prophetic god.

Thus does Kitto comment on the words of Isaiah xlvi. 1: “Bel boweth down, Nebo stoppet ,” with reference to the latter name: “The word seems to come from Nibba, to deliver an oracle, or to prophesy; and hence would mean an ‘oracle,’ and may thus, as Calmet suggests, (‘Commentaire Literal,’ in loc.) be no more than another name for Bel himself, or a characterizing epithet applied to him; it being not unusual to repeat the same thing, in the same verse, in equivalent terms.” “Zer-Nebo-Gus,” the great “seed of the prophet Cush,” was, of course, Nimrod; for Cush was Nimrod’s father.

Turn now to Layard, and see how this land of ours and Assyria are thus brought into intimate connection. In the woodcut referred to, first we find “the Assyrian Hercules,” that is “Nimrod the giant,” as he is called in the Septuagint version of Genesis, without club, spear, or weapons of any kind, attacking a bull. Having overcome it, he sets the bull’s horns on his head, as a trophy of victory and a symbol of power; and thenceforth the hero is represented, not only with the horns and hoofs above, but from the middle downwards, with the legs and cloven feet of the bull. Thus equipped, he is represented as turning next to encounter a lion. This, in all likelihood, is intended to commemorate some event in the life of him who first began to be mighty in the chase and in war, and who, according to all ancient traditions, was remarkable also for bodily power, as being the leader of the Giants who rebelled against heaven.

Now Nimrod, as the son of Cash, was black, in other words, was a negro. “Can the Ethiopian change his skin?” is in the original, “Can the Cushite” do so? Keeping this, then, in mind, it will be seen, that in that figure disentombed from Nineveh, we have both the prototype of the Anglo-Saxon Zer-Nebo—Gus, “the seed of the prophet Cush,” and the real original of the black Adversary of mankind, with horns and hoofs. It was in a different character from that of the Adversary that Nimrod was originally worshiped; but among a people of a fair complexion, as the Anglo-Saxons, it was inevitable, that if worshiped at all, it must generally be simply as an object of fear; and so Kronos, “The Horned one,” who wore the “horns,” as the emblem both ‘of his physical might and sovereign power, has come to be, in popular superstition, the recognized representative of the Devil.

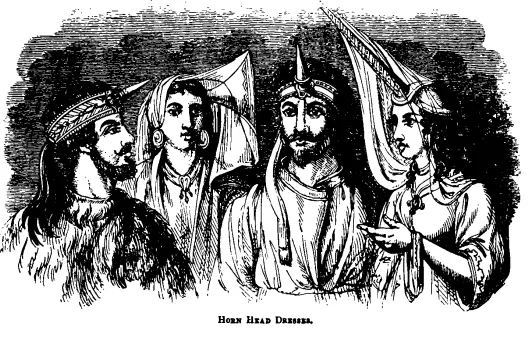

In many and far-severed countries, horns became the symbols of sovereign power. The corona or crown, that still encircles the brows of European monarchs, seems remotely to be derived from the emblem of might adopted by Kronos, or Saturn, who, according to Pherecydes, was “the first before all others that ever wore a crown.” The first regal crown appears to have been only a band, in which the horns were set. From the idea of power contained in the “ horn,” even subordinate rulers seem to have worn a circlet adorned with a single horn, in token of their derived authority. Bruce, the Abyssinian traveler, gives examples of Abyssinian chiefs thus decorated (fig. 11); in regard to whom he states that the horn attracted his particular attention, when he perceived that the governors of provinces were distinguished by this headdress.

In the case of sovereign powers, the royal head-band was adorned sometimes with a double, sometimes with a triple horn. The double horn had evidently been the original symbol of power or might on the part of sovereigns; for, on the Egyptian monuments, the heads of the deified royal personages have generally no more than the two horns to shadow forth their power.

As sovereignty in Nimrod’s case was founded on physical force, so the two horns of the bull were the symbols of that physical force. And, in accordance with this, we read in “Sanchuniathon,” that “ Astarte put on her own head a bull’s head, as the ensign of royalty.” By and by, however, another and a higher idea came in, and the expression of that idea was seen in the symbol of the three horns.

A cap seems in course of time to have come to be associated with the regal horns. In Assyria the three-horned cap was one of the “sacred emblems,” in token that the power connected with it was of celestial origin,—the three horns evidently pointing at the power of the Trinity. Still we have indications that the horned band, without any cap, was anciently the corona or royal crown. The crown borne by the Hindu god Vishnu, in his avatar of the Fish, is just an open circle or band, with three horns standing erect from it, with a knob on the top of each horn (fig. 12).

All the avatars are represented as crowned with a crown that seems to have been modeled from this, consisting of a coronet with three points standing erect from it, in which Sir William Jones recognizes the Ethiopian or Parthian coronet. The open tiara of Agni, the Hindu god of fire, shows in its lower round the double horn made in the very same way as in Assyria, proving at once the ancient custom, and whence that custom had come. Instead of the three horns, three horn—shaped leaves came to be substituted (fig. 13); and thus the horned band gradually passed into the modern coronet or crown with the three leaves ‘ of the fieur-de-lis, or other familiar three-leaved adornings.

Among the Red Indians of America there had evidently been something entirely analogous to the Babylonian custom of wearing the horns; for, in the “buffalo dance” there, each of the dancers had his head arrayed with buffalo’s horns; and it is worthy of especial remark, that the “Satyric dance,” or dance of the Satyrs in Greece, seems to have been the counterpart of this Red Indian solemnity; for the satyrs were horned divinities, and consequently those who imitated their dance must have had their heads set off in imitation of theirs. When thus we find a custom that is clearly founded on a form of speech that characteristically distinguished the region where Nimrod’s power was wielded, used in so many different countries far removed from one another, where no such form of speech was used in ordinary life, we may be sure that such a custom was not the result of mere accident, but that it indicates the wide-spread diffusion of an influence that went forth in all directions from Babylon, from the time that Nimrod first “ began to be mighty on the earth.”

There was another way in which Nimrod’s power was symbolized besides by the “horn.” A synonym for Gheber, “The mighty one,” was “Abir,” while “Aber” also signified a “wing.” Nimrod, as Head and Captain of those men of war, by whom he surrounded himself, and who were the instruments of establishing his power, was “Baal-abirin,” “Lord of the mighty ones.” But “ Baal-aberin” (pronounced nearly in the same way) signified “The winged one,” and therefore in symbol he was represented, not only as a horned bull, but as at once a horned and winged bull—as showing not merely that he was mighty himself, but that he had mighty ones under his command, who were ever ready to carry his will into effect, and to put down all opposition to his power; and to shadow forth the vast extent of his might, he was represented with great and wide-expanding wings.

To this mode of representing the mighty kings of Babylon and Assyria, who imitated Nimrod and his successors, there is manifest illusion in Isaiah viii. 6—8: “Forasmuch as this people refuseth the waters of Shiloah that go softly, and rejoice in Rezin and Remaliah’s ,son; now therefore, behold the Lord bringeth up upon them the waters of the river, strong and mighty, even the king of Assyria, and all his glory; and he shall come up over all his banks. And he shall pass through Judah; he shall overflow and go over; he shall reach even unto the neck; and the STRETCHING OUT OF HIS WINGS shall FILL the breadth of thy land, O Immanuel.”

When we look at such figures as those which are here presented to the reader (figs. 14 and 15), with their great extent of expanded wing, as symbolizing an Assyrian king, what a vividness and force does it give to. the inspired language of the prophet! And how clear is it, also, that the stretching forth of the Assyrian monarch’s WINGS, that was to “fill the breadth of Immanuel’s land,” has that very symbolic meaning to which I have referred, viz., the overspreading of the land by his “mighty ones,” or hosts of armed men, that the king of Babylon was to bring with him in his overflowing invasion! The knowledge of the way in which the Assyrian monarchs were represented, and of the meaning of that representation, gives additional force to the story of the dream of Cyrus the Great, as told by Herodotus.

Cyrus, says the historian, dreamt that he saw the son of one of his princes who was at the time in a distant province, with two great “wings on his shoulders, the one of which overshadow Asia, and the other Europe,” from which he immediate ly concluded that he was organizing rebellion against him.The symbols of the Babylonians, whose capital Cyrus had taken, and to whose power he had succeeded, were entirely familiar to him, and if the “wings” were the symbols of sovereign power, and the possession of them implied the lordship over the might, or the armies of the empire, it is easy to see how very naturally any suspicions of disloyalty affecting the individual in question might take shape in the manner related, in the dreams of “him who might harbour these suspicions.

Now the understanding of this equivocal sense of “Baalaberin” can alone explain the remarkable statement of Aristphanes, that at the beginning of the world “the birds” were first created, and then, after their creation, came the “race of the blessed immortal gods.” This has been regarded as either an atheistical or nonsensical utterance on the part of the poet, but with the true key applied to the language, it is found to contain an important historical fact. Let it only be borne in mind that “the birds” ——that is, “the winged ones”-—symbolized “the Lords of the mighty ones,” and then the meaning is clear: viz., that men first “began to be mighty on the earth,” and then, that the “Lords,” or Leaders of “these mighty ones” were deified.

The knowledge of the mystic sense of this symbol accounts also for the origin of the story of Perseus, the son of Jupiter, miraculously born of Danaé, who did such wondrous things, and who passed from country to country on wings divinely bestowed on him. This equally casts light on the symbolic myths in regard to Bellerophon, and the feats which he performed on his winged horse, and their ultimate disastrous issue; how high he mounted in the air, and how terrible was his fall; and of Icarus, the son of Daedalus, who, flying on wax-cemented wings over the Icarian sea, had his wings melted off through his too near approach to the sun, and so gave his name to the sea where he was supposed to have fallen. These fables all referred to those who trode, or were supposed to have trodden, in the steps of Nimrod, the first “Lord of the mighty ones,” and who in that character was symbolized as equipped with wings.

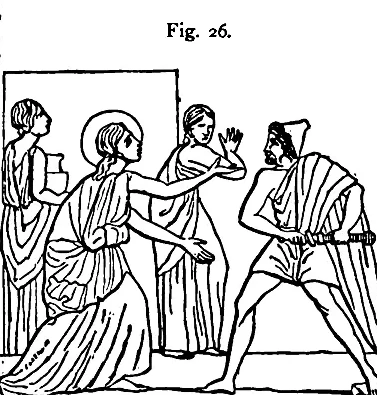

Now, it is remarkable that, in the passage of Aristophanes already referred to, that speaks of the birds, or “the winged ones,” being produced before the gods, we are informed that he from whom both “mighty ones” and gods derived their origin, was none other than the winged boy Cupid. Cupid, the son of Venus, occupied, as will afterwards be proved, in the mystic mythology the very same position as Nin, or Ninus, “the son,” did to Rhea, the mother of the gods. As Nimrod was unquestionably the first of “the mighty ones” after the flood, this statement of Aristophanes, that the boy-god Cupid, himself a winged one, produced all the birds or “winged ones,” while occupying the very position of Nin or Ninus, “the son,” shows that in this respect also Ninus and Nimrod are identified. While this is the evident meaning of the poet, this also, in a strictly historical point of view, is the conclusion of the historian Apollodorus; for he states that “Ninus is Nimrod.” And then, in conformity with this identity of Ninus and Nimrod, we find, in one of the most celebrated sculptures of ancient Babylon, Ninus and his wife Semiramis represented as actively engaged in the pursuits of the chase—“the quiver-bearing Semiramis” being a fit companion for “the mighty Hunter before the Lord.”

Sub-Section II. The Child in Egypt

When we turn to Egypt, we find remarkable evidence of the same thing there also. Justin, as we have already seen, says that “Ninus subdued all nations, as far as Lybia,” and consequently Egypt. The statement of Diodorus Siculus is to the same effect, Egypt being one of the countries that, according to him, Ninus brought into subjection to himself. In exact accordance with these historical statements, we find that the name of the third person in the primeval triad of Egypt was Khons. But Khons, in Egyptian, comes from a word that signifies “to chase.” Therefore, the name of Khons, the son of Maut, the goddess mother, who was adorned in such a way as to identify her with Rhea, the great Goddess mother of Chaldea, properly signifies “The Huntsman,” or god of the chase.

As Khon stands in the very same relation to the Egyptian Maut as Ninus does to Rhea, how does this title of “The Huntsman” identify the Egyptian god with Nimrod? Now this very name Khons, brought into contact with the Roman mythology, not only explains the meaning of a name in the Pantheon there, that hitherto has stood greatly in need of explanation, but causes that name, when explained, to reflect light back again on this Egyptian divinity,and to strengthen the conclusion already arrived at. The name to which I refer is the name of the Latin god Consus, who was in one aspect identified with Neptune, but was also regarded as “the god of hidden counsels,” or “the concealer of secrets,” who was looked up to as the patron of horsemanship, and was said to have produced the horse. Who could have been the “god of hidden counsels,” or the “concealer of secrets,” but Saturn, the god of the “mysteries,” and whose name, as used at Rome, signified “ The hidden one?”

The father of Khons, or Khonso (as he was also called), that is, Amoun, was, as we are told by Plutarch, known as “The hidden God;” and as father and son in the same triad have ordinarily a correspondence of character, this shows that Khons also must have been known in the very same character of Saturn, “The hidden one.” If the Latin Consus, then, thus exactly agreed with the Egyptian Khons, as the god of “Mysteries,” or “hidden counsels,” can there be a doubt that Khons, the Huntsman, also agreed with the same Roman divinity as the supposed producer of the horse? Who so likely to get the credit of producing the horse as the great huntsman of Babel, who no doubt enlisted it in the toils of the chase, and by this means must have been signally aided in his conflicts with the wild beasts of the forest? In this connection, let the reader call to mind that fabulous creature, the Centaur, half-man, half-horse, that figures so much in the mythology of Greece. That imaginary creation, as is generally admitted, was intended to commemorate the man who first taught the art of horsemanship. But that creation was not the offspring of Greek fancy. Here, as in many other things, the Greeks have only borrowed from an earlier source. The Centaur is found on coins struck in Babylonia, (fig. 16), showing that the idea must have originally come from that quarter.

The Centaur is found in the Zodiac (fig. 17),: the antiquity of which goes up to a high period, and which had its origin in Babylon. The Centaur was represented, as we are expressly assured by Berosus, the Babylonian historian, in the temple of Babylon, and his language would seem to show that so also it had been in primeval times The Greeks did themselves admit this antiquity and derivation of the Centaur; for though Ixion was commonly represented as the father of the Centaurs, yet they also acknowledged, that the primitive Centaurus Was the same as Kronos, or Saturn, the father of the gods. But we have seen that Kronos was the first King of Babylon, or Nimrod; consequently, the first Centaur was the same. Now the way in which the Centaur was represented on the Babylonian coins, and in the Zodiac, viewed in this light, is very striking. The Centaur was the same as the sign Sagittarius, or “The Archer.”

Fig. 17 Sagittarius, or “The Archer.”

If the founder of Babylon’s glory was “The mighty Hunter,” whose name, even in the days of Moses, was a proverb,—(Gen. x. 9, “Wherefore it is said, Even as Nimrod, the mighty hunter before the Lord”)—when we find the “Archer,” with his bow and arrow, in the symbol of the supreme Babylonian divinity, and the “Archer,” among the signs of the Zodiac that originated in Babylon, I think we may safely conclude that this Man-horse or Horseman Archer primarily referred to him, and was intended to perpetuate the memory at once of his fame as a huntsman and his skill as a horse-breaker.

Now, when we thus compare the Egyptian Khons, the “Huntsman,” with the Latin Consus, the god of horse-races, who “produced the horse,” and the Centaur of Babylon, to whom was attributed the honor of being the author of horsemanship, while we see how all the lines converge in Babylon, it will be very clear, I think, whence the primitive Egyptian god Khons has been derived.

Khons, the son of the great goddess-mother, seems to have been generally represented as a full-grown god. The Babylonian divinity was also represented very frequently in Egypt in the very same way as in the land of his nativity, i.e., as a child in his mother’s arms. This was the way in which Osiris, “the son, the husband of his mother,” was Often exhibited, and what we learn of this god, equally as in the case of Khonso, shows that in his original he was none other than Nimrod.

It is admitted that the secret system of Free Masonry was originally founded on the Mysteries of the Egyptian Isis, the goddess-mother, or wife of Osiris. But what could have led to the union of a Masonic body with these Mysteries, had they not had particular reference to architecture, and had the god who was worshiped in them not been celebrated for his success in perfecting the arts of fortification and building? Now, if such were the case, considering the relation in which, as we have already seen, Egypt stood to Babylon, who would naturally be looked up to there as the great patron of the Masonic art? The strong presumption is, that Nimrod must have been the man. He was the first that gained fame in this way. As the child of the Babylonian goddess-mother, he was worshiped, as we have seen, in the character of Ala mahozim, “The god of fortifications.”

Osiris, in like manner, the child of the Egyptian Madonna, was equally celebrated as “the strong chief of the buildings.” This strong chief of the buildings was originally worshiped in Egypt with every physical characteristic of Nimrod. I have already noted the fact, that Nimrod, as the son of Cush, was a negro. Now, there was a tradition in Egypt, recorded by Plutarch, that “Osiris was black,” which, in a land where the general complexion was dusky, must have implied something more than ordinary in its darkness. Plutarch also states that Horus, the son of Osiris, “was of a fair complexion,” and it was in this way, for the most part, that Osiris was represented. But we have unequivocal evidence that Osiris, the son and husband of the great goddess-queen of Egypt, was also represented as a veritable negro. In Wilkinson may be found a representation of him (fig. 18) with the unmistakable features of the genuine Cushite or negro. Bunsen would have it that this is a mere random importation from some of the barbaric tribes; but the dress in which this negro god is arrayed tells a different tale. That dress directly connects him with Nimrod. This negro-featured Osiris is clothed from head to foot in a spotted dress, the upper part being a leopard’s skin, the under part also being spotted to correspond with it.

Now the, name Nimrod signifies “The subduer of the leopard.” This name seems to imply, that as Nimrod had gained fame by subduing the horse, and so making use of it in the chase, so his fame as a huntsman rested mainly on this, that he found out the art of making the leopard aid him in hunting the other wild beasts. A particular kind of tame leopard is used in India at this day for hunting; and. of Bagajet I., the Mogul Emperor of India, it is recorded that, in his hunting establishment, he had not only hounds of various breeds, but leopards also, whose “collars were set with jewels.”

Upon the words of the prophet Habakkuk, chap. i. 8, “swifter than leopards,” Kitto has the following remarks:—“The swiftness of the leopard is proverbial in all countries where it is found. This, conjoined with its other qualities, suggested the idea in the East of partially training it, that it might be employed in hunting….. Leopards are now rarely kept for hunting in Western Asia, unless by kings and governors; but they are more common in the eastern parts of Asia. Orosius relates that one was sent by the king of Portugal to the Pope, which excited great astonishment by the way in which it overtook, and the facility with which it killed, deer and wild boars. Le Bruyn mentions a leopard kept by the Pasha who governed Gaza, and the other territories of the ancient Philistines, and which be frequently employed in hunting jackals. But it is in India that the cheetah or hunting leopard is most frequently employed, and is seen in the perfection of his power.”

This custom of taming the leopard, and pressing it into the service of man in this way, is traced up to the earliest times of primitive antiquity. In the works of Sir William Jones, we find it stated from the Persian legends, that Hoshang, the father of Tahmurs, who built Babylon, was the “first who bred dogs and leopards for hunting.” As Tahmurs, who built Babylon, could be none other than Nimrod, this legend only attributes to his father what, as his name imports, he got the fame of doing himself.

Now, as the classic god bearing the lion’s skin is recognized by that sign as Hercules, the slayer of the Nemean lion, so, in like manner, the god clothed in the leopard’s skin, would naturally be marked out as Nimrod, the “Leopard-subduer.” That this leopard skin, as appertaining to the Egyptian god, was no occasional thing, we have clearest evidence. Wilkinson tells us, that on all high occasions when the Egyptian high priest was called to officiate, it was indispensable that he should do so wearing, as his robe of office, the leopard’s skin (fig. 19). As it is a universal principle in all idolatries that the high priest wears the insignia of the god he serves, this indicates the importance which the spotted skin must have had attached to it as a symbol of the god himself.

The ordinary way in which the favorite Egyptian divinity Osiris was mystically represented was under the form of a young bull or calf—the calf Apis—from which the golden calf of the Israelites was borrowed. There was a reason why that calf should not commonly appear in the appropriate symbols of the god here presented,for that calf represented the divinity in the character of Saturn, “The HIDDEN one,” “Apis” being only another name for Saturn. The cow of Athor, however, the female divinity, corresponding to Apis, is well known as a “spotted cow; and it is singular that the Druids of Britain also worshiped “a spotted cow.” Rare though it be, however, to find an instance of the deified calf or young bull represented with the spots, there is evidence still in existence, that even it was sometimes so represented.

The ordinary way in which the favorite Egyptian divinity Osiris was mystically represented was under the form of a young bull or calf—the calf Apis—from which the golden calf of the Israelites was borrowed. There was a reason why that calf should not commonly appear in the appropriate symbols of the god here presented,for that calf represented the divinity in the character of Saturn, “The HIDDEN one,” “Apis” being only another name for Saturn. The cow of Athor, however, the female divinity, corresponding to Apis, is well known as a “spotted cow; and it is singular that the Druids of Britain also worshiped “a spotted cow.” Rare though it be, however, to find an instance of the deified calf or young bull represented with the spots, there is evidence still in existence, that even it was sometimes so represented.

The accompanying figure (fig. 20), represents that divinity, as copied by Col. Hamilton Smith “from the original collection made by the artists of the French Institute of Cairo.“ When we find that Osiris, the grand god of Egypt, under different forms, was thus arrayed in a leopard’s skin or spotted dress, and that the leopard—skin dress was so indispensable a part of the sacred robes of his high priest, we may be sure that there was a deep meaning in such a costume. And what could that meaning be, but just to identify Osiris with the Babylonian god, who was celebrated as the “Leopard-tamer,” and who was worshiped even as he was, as Ninus, the CHILD in his mother’s arms?

Sub-Section III. The Child in Greece

Thus much for Egypt. Coming into Greece, not only do we find evidence there to the same effect, but increase of that evidence. The god worshiped as a child in the arms of the great Mother in Greece, under the names of Dionysus, or Bacchus, or Iacchus, is, by ancient inquirers, expressly identified with the Egyptian Osiris. This is the case with Herodotus, who had prosecuted his inquiries in Egypt itself, who ever speaks of Osiris as Bacchus. To the same purpose is the testimony of Diodorus Siculus. “Orpheus,” says he, “introduced from Egypt the greatest part of the mystical ceremonies, the orgies that celebrate the wanderings of Ceres, and the whole fable of the shades below. The rites of Osiris and Bacchus are the same; those of Isis and Ceres exactly resemble each other, except in name.”

Now, as if to identify Bacchus with Nimrod, “the Leopard-tamer,” leopards were employed to draw his car; he himself was represented as clothed with a leopard’s skin; his priests were attired in the same manner, or when a leopard’s skin was dispensed with, the spotted skin of a fawn was used as the priestly robe in its stead. This very custom of wearing the spotted fawn-skin seems to have been imported into Greece originally from Assyria, where a. spotted fawn was a sacred emblem, as we learn from the Nineveh sculptures; for there we find a divinity bearing a spotted fawn, or spotted fallow-deer (fig. 21), in his arm, as a symbol of some mysterious import.

The origin of the importance attached to the spotted fawn and its skin, had evidently come thus: When Nimrod, as the “Leopard-tamer,” began to be clothed in the leopard-skin, as the trophy of his skill, his spotted dress and appearance must have impressed the imaginations of those who saw him; and he came to be called not only the “Subduer of the Spotted one,” (for such is the precise meaning of Nimr—the name of the leopard), but to be called “The spotted one” himself.

We have distinct evidence to this effect borne by Damascius, who tells us that the Babylonians called “the only son” of their great Goddess Mother “ Momis, or Moumis.” Now, Momis, or Moumis, in Chaldee, like Nimr, signified “The spotted one.” Thus, then, it became easy to represent Nimrod by the symbol of the “spotted fawn,” and especially in Greece, and wherever a pronunciation akin to that of Greece prevailed.

The name of Nimrod, as known to the Greeks, was Nebrod. The name of the fawn, as “the spotted one,” in Greece was Nebros; and thus nothing could be more natural than that Nebros, the “spotted fawn,” should become a synonym for Nebrod himself. When, therefore, the Bacchus of Greece was symbolized by the Nebros, or “spotted fawn,” as we shall find he was symbolized, what could be the design but just covertly to identify him with Nimrod?

We have evidence that this god, whose emblem was the Nebros, was known as having the very lineage of Nimrod. From Anacreon, we find that a title of Bacchus was Aithiopais, i.e., “the son of AEthiops.” But who was AEthiops? As the Ethiopians were Cushites, so AEthiops was Cush. “Chus,” says Eusebius, “was he from whom came the Ethiopians.” The testimony of Josephus is to the same effect. As the father of the Ethiopians, Cush was AEthiops, by way of eminence. Therefore Epiphanius, referring to the extraction of Nimrod, thus speaks: “Nimrod, the son of Cush, the AEthiop.”

Now, as Bacchus was the son of AEthiops, or Cush, so to the eye he was represented in that character. As Nin “the Son,” he was portrayed as a youth or child, and that youth or child was generally depicted with a cup in his hand. That cup, to the multitude, exhibited him as the god of drunken revelry; and of such revelry in his orgies, no doubt there was abundance; but yet, after all, the cup was mainly a hieroglyphic, and that of the name of the god.

The name of a cup, in the sacred language, was khus, and thus the cup in the hand of the youthful Bacchus, the son of AEthiops, showed that he was the young Chus, or the son of Chus. In the accompanying woodcut (fig. 22), the cup in the right hand of Bacchus is held up in so significant a way, as naturally to suggest that it must be a symbol; and as to the branch in the other hand, We have express testimony that it is a symbol. But it is worthy of notice that the branch has no leaves to determine what precise kind of branch it is. It must, therefore, be a generic emblem for a branch, or a symbol of a branch in general; and, consequently, it needs the cup as its complement, to determine specifically what sort of a branch it is. The two symbols, then, must be read together; and read thus, they are just equivalent to—the “Branch of Chus,” i.e., “ the scion or son of Cush.”

There is another hieroglyphic connected with Bacchus that goes not a little to confirm this; that is, the Ivy branch. No emblem was more distinctive of the worship of Bacchus than this. Wherever the rites of Bacchus were performed, wherever his orgies were celebrated, the Ivy branch was sure to appear. Ivy, in some form or other, was essential to these celebrations. The votaries carried it in their hands, bound it around their heads, or had the Ivy leaf even indelibly stamped upon their persons. What could be the use, what could be the meaning of this? A few words will suffice to show it. In the first place, then, we have evidence that Kissos, the Greek name for Ivy, was one of the names of Bacchus, and further, that though the name of Cush, in its proper form, was known to the priests in the mysteries, yet that the established way in which the name of his descendants, the Cushites, was ordinarily pronounced in Greece, was not after the Oriental fashion, but as “Kissaioi,” or “Kissioi.” Thus Strabo, speaking of the inhabitants of Susa, who were the people of Chusistan, or the ancient land of Cash, says: “The Susians are called Kissioi,” that is, beyond all question, Cushites. Now, if Kissioi be Cushites, then Kissos is Cush.

Then, further, the branch of Ivy that occupied so conspicuous a place in all Bacchanalian celebrations was an express symbol of Bacchus himself; for Hesychius assures us that Bacchus, as represented by his priest, was known in the mysteries as “The branch.”’ From this, then, it appears how Kissos, the Greek name of Ivy, became the name of Bacchus. As the son of Cush, and as identified with him, he was sometimes called by his father’s name— Kissos. His actual relation, however, to his father was specifically brought out by the Ivy branch; for “the branch of Kissos,” which to the profane vulgar was only “the branch of Ivy,” was to the initiated “the branch of Cush.”

Now, this god, who was recognized as “the scion of Cush,” was worshiped under a name, which, while appropriate to him in his vulgar character as the god of the vintage, did also describe him as the great Fortifier. That name was Bassareus, which in its twofold meaning, signified at once “The houser of grapes, or the vintage gatherer,” and “The Encompasser with a wall,” in this latter sense identifying the Grecian god with the Egyptian Osiris, “the strong chief of the buildings,” and with the Assyrian “Belus, who encompassed Babylon with a wall.”

Thus from Assyria, Egypt, and Greece, we have cumulative and overwhelming evidence, all conspiring to demonstrate that the child worshiped in the arms of the goddess-mother in all these countries in the very character of Ninus or Nin, “The Son,” was Nimrod, the son of Cush. A feature here, or an incident there, may have been borrowed from some succeeding hero; but it seems impossible to doubt, that of that child Nimrod was the prototype, the grand original.

The amazing extent of the worship of this man indicates something very extraordinary in his character; and there is ample reason to believe, that in his own day he was an object of high popularity. Though by setting up as king, Nimrod invaded the patriarchal system, and abridged the liberties of mankind, yet he was held by many to have conferred benefits upon them, that amply indemnified them for the loss of their liberties, and covered him with glory and renown. By the time that he appeared, the wild beasts of the forest multiplying more rapidly than the human race, must have committed great depredations on the scattered and straggling populations of the earth, and must have inspired great terror into the minds of men. The danger arising to the lives of men from such a source as this, when population is scanty, is implied in the reason given by God himself for not driving out the doomed Canaanites before Israel at once, though the measure of their iniquity was full: (Exod. xxiii. 29, 30), “I will not drive them out from before thee in one year, lest the land become desolate, and the beast of the field multiply against thee. By little and little I will drive them out from before thee, until thou be increased.”

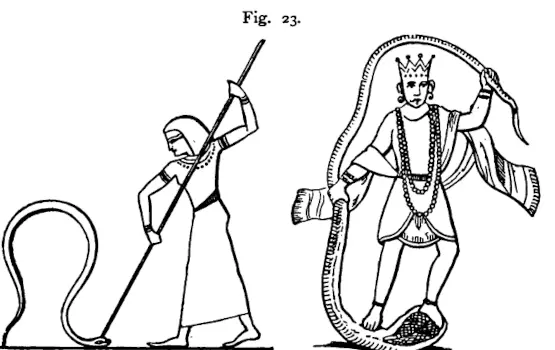

The exploits of Nimrod, therefore, in hunting down the wild beasts of the field, and ridding the world of monsters, must have gained for him the character of a pre—eminent benefactor of his race. By this means, not less than by the bands he trained, was his power acquired when he first began to be mighty upon the earth; and in the same way, no doubt, was that power consolidated. Then over and above, as the first great city-builder after the flood, by gathering men together in masses, and surrounding them with walls, he did still more to enable them to pass their days in security, free from the alarms to which they had been exposed in their scattered life, when no one could tell but that at any moment he might be called to engage in deadly conflict with prowling wild beasts, in defense of his own life and of those who were dear to him. Within the battlements of a fortified city no such danger from savage animals was to be dreaded; and for the security afforded in this way, men no doubt looked upon themselves as greatly indebted to Nimrod. No wonder, therefore, that the name of the “mighty hunter,” who was at the same time the prototype of “the god of fortifications,” should have become a name of renown. Had Nimrod gained renown only thus, it had been well. But not content with delivering men from the fear of wild beasts, he set to work also to emancipate them from that fear of the Lord which is the beginning of wisdom, and in which alone true happiness can be found. For this very thing, he seems to have gained, as one of the titles by which men delighted to honour him, the title of the “Emancipator,” or “ Deliverer.”

The reader may remember a name that has already come under his notice. That name is the name of Phoroneus. The era of Phoroneus is exactly the era of Nimrod. He lived about the time when men had used one speech, when the confusion of tongues began, and when mankind was scattered abroad. He is said to have been the first that gathered mankind into communities, the first of mortals that reigned; and the first that offered idolatrous sacrifices. This character can agree with none but that of Nimrod.

Now, the name given to him in connection with his “gathering men together,” and offering idolatrous sacrifice, is very significant. Phoroneus, in one of its meanings, and that one of the most natural, signifies “The Apostate.” That name had very likely been given him by the uninfected portion of the sons of Noah. But that name had also another meaning, that is, “to set free;” and therefore his own adherents adopted it, and glorified the great “Apostate” from the primeval faith, though he was the first that abridged the liberties of mankind, as the grand “Emancipator!”

And hence, in one form or other, this title was handed down to his deified successors as a title of honor. All tradition from the earliest times bears testimony to the apostasy of Nimrod, and to his success in leading men away from the patriarchal faith, and delivering their minds from that awe of God and fear of the judgments of heaven that must have rested on them while yet the memory of the flood was recent. And according to all the principles Of depraved human nature, this too, no doubt, was one grand element in his fame: for men will readily rally around any one can give the least appearance of plausibility to an doctrine Which will teach that they can be assured of happiness and Heaven at last, though their hearts and natures are unchanged, and though they live without God in the world.