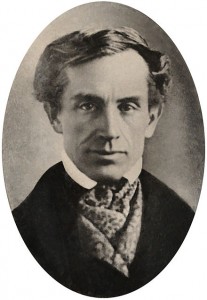

Samuel Morse

- The political character of this ostensibly religious enterprise proved from the letters of the Jesuits now in this country

- Their antipathy to private judgment

- Their anticipations of a change of our form of government

- Our government declared too free for the exercise of their divine rights

- Their political partialities

- Their cold acknowledgment of the generosity, and liberality, and hospitality of our government

- Their estimate of our condition contrasted with their estimate of that of Austria

- Their acknowledged allegiance and servility to a foreign master

- Their sympathies with the oppressor, and not with the oppressed

- Their direct avowal of political intention.

LET me next show the political character of this ostensibly religious effort, from the sentiments of the Austrian emissaries expressed to their foreign patrons. The very nature of a conspiracy of this kind precludes the possibility of much direct evidence of political design; for Jesuit cunning and Austrian duplicity would be sure to tread with unusual caution on American ground. Yet if I can quote from their correspondence some expressions of antipathy to our free principles, and to the government; some hinting at the subversion of the government; prevailing partialities for arbitrary government; and siding with tyranny against the oppressed; and some acknowledgments of POLITICAL EFFECTS to be expected from the operations of the society, I shall have exhibited evidence enough to put every citizen who values his birthright, upon the strict watch of these men and their adherents, and to show the importance of some measures of repelling this insidious invasion of the country.

The Bishop of Baltimore writing to the Austrian Society, laments the wretched state of the Catholic religion in Virginia, and as a proof of the difficulty it has to contend with, (a proof doubtless shocking to the pious docility of his Austrian readers,) he says:

“I sent to Richmond a zealous missionary, a native of America. He travelled through the whole of Virginia. The Protestants flocked on all sides to hear him, they offered him their churches, courthouses, and other public buildings, to preach in, which however is not at all surprising, for the people are divided into numerous sects, and know not what faith to embrace. In consequence of being spoiled by bad instruction, they will judge every thing themselves; they, therefore, hear eagerly every new comer,” &c.

The Bishop, if he had the power, would of course change this “bad instruction” for better, and, as in Catholic countries, would relieve them from the trouble of judging for themselves. Thus the liberty of private judgment and freedom of opinion, guaranteed by our institutions, are avowedly an obstacle to the success of the Catholics. Is it not natural that Catholics should desire to remove this obstacle out of their way? Footnote: A Catholic journal of this city, (the Register and Diary,) was put into my hands as I has completed this last paragraph. It contains the same sentiment, so illustrative of the natural abhorrence of Catholics to the exercise of private judgment, that I cannot forbear quoting it.

“We seriously advise Catholic parents to be very cautious in the choice of school-books for their children. There is more danger to be apprehended in this quarter, than could be conceived. Parents, we are aware, have not always the time or patience to examine these matters: but if they trust implicitly to us, we shall with God’s help, do it for them. Legimus ne legantur.” We read, that they may not read !!

How kind! they will save parents all the trouble of judging for themselves, but “we must be trusted implicitly” Would a Protestant journal thus dare to take liberties with its readers?

My Lord Bishop Flaget, of Bardstown, Kentucky, in a. letter to his patrons abroad, has this plain hint at an ulterior political design, and that no less that the entire subversion of our republican government. Speaking of the difficulties and discouragements the Catholic missionaries have to contend with in converting the Indians, the last difficulty in the way he says, is “their continual traffic among the whites, WHICH CANNOT BE HINDERED AS LONG AS THE REPUBLICAN GOVERNMENT SHALL SUBSIST!” What is this but saying , that a republican government is unfavorable in its nature to the restrictions we deem necessary to the extension of the Catholic religion; when the time shall come that the present government shall be subverted, which we are looking forward to, or hope for, we can then hinder this traffic?

Mr. Baraga, the German missionary in Michigan, seems impressed with the same conviction of the unhappy influence of a free government upon his attempts to make converts to the church of Rome. In giving an account of the refusal of some persons to have their children baptized, he lays the fault on this, “TOO FREE (allzu freien) GOVERNMENT.” In a more despotic government, in Italy or Austria, he would have been able to put in force compulsory baptism on these children. Footnote: Compulsory Baptism. Perhaps Father Baraga was thinking of the facilities afforded in Spain in the time of Ximenes for administering baptism, when “Fifty thousand (50,000,) Moors under terror of death and torture received the grace of baptism, and more than an equal number of the refractory were condemned, of whom 2,536 were burnt alive.” May our government long be “too free” for the enacting of such barbarity.

These few extracts are quite sufficient to show how our form of government, which gives to the Catholics all the freedom and facilities that other sects enjoy, does from its very nature embarrass their despotic plans. Accustomed to dictate at home, how annoying it is to these Austrian ecclesiastics to be obliged to put off their authority, to yield their divine right of judging for others, to be compelled to get at men through their reason and conscience, instead of the more summary way of compulsion! The disposition to use force if they could, shows itself in spite of all their caution. The inclination is there. It is reined in by circumstances. They want only strength to act out the inherent despotism of Popery.

But let me show what are some of the political partialities which these foreign emissaries discover in their letters and statements to their Austrian supporters. They acknowledge their unsuspicious reception by the people of the United States; they acknowledge that Protestants in all parts of the country have even aided them with money to build their chapels and colleges and nunneries, and treated them with liberality and hospitality, and-strange infatuation!!-have been so monstrously foolish as to intrust their children to them to be educated! so infatuated as to confide in their honor and in their promises that they would use no attempts to proselyte them! And with all this, does it not once occur to these gentleman, that this liberality, and generosity and openness of character are the fruits of Protestant republicanism? Might we not expect at least that Popery, were it republican in its nature, would find something in all this that would excite admiration, and call forth some praise of a system so contrasted to that of any other government; some acknowledgments to the government of the country that protects it, and allows its emissaries the unparalleled liberty even to plot the downfall of the state? But no, the government of the United States is not once mentioned in praise. The very principle of the government, through which they are tolerated, is thus slightingly noticed: “The government of the United States has thought fit to adopt a complete indifference toward all religions.” Footnote: Quart. Regist. Feb. 1830, p. 198. They can recognize no nobler principle than indifference.

Again, of the people of our country they thus write: “We intreat all European Christians to unite in prayer to God for the conversion of these unhappy heathen, and obstinate heretics.” We are spoken of as a country “on which the light of faith has hitherto not shined.” “A vast country, destitute of all spiritual and temporal resources.” But if Austria is mentioned, what are the terms? “Your Society, (the Leopold Foundation) which is an ornament to the illustrious Austrian Empire,”-” the noble and generous inhabitants of the Austrian empire .” ” Of many circumstances in our condition, few perhaps in your happy empire can form a correct notion;” and again, “Here are many churches, if you may so call the miserable wooden buildings, differing little from the barns of your happy land!” Austria, happy land!! How enthusiastic, too, is another Bishop, who writes, “we cannot sufficiently praise our good Emperor (of Austria,) were we to extol him to the third heaven!” Such are the political partialities which are discovered in various parts of these documents. Are they in favor of our republican darkness, and heathenism, and misery, or of Austrian light, and piety and happiness?

In the struggles of the European people for their liberty, do these foreign teachers sympathize with the oppressor or with the oppressed? “France no more helps us,” (Charles X. had just been dethroned,) “and Rome, beset by enemies to the church and public order, is not in a condition to help us.” And who are these men stigmatized as enemies of public order? They are the Italian patriots of the Revolution of 1831, than whom our own country in the perils of its own Revolution did not produce men more courageous, more firm, more wise, more tolerant, more patriotic; men who had freed their country from the bonds of despotism in a struggle almost bloodless, for the people were with them; men who, in the spirit of American patriots, were organizing a free government; rectifying the abuses of Papal misrule, and who, in the few weeks of their power, had accomplished years of benefit. These are the men afterwards dragged to death, or to prison by Austrian intruders, and styled by our Jesuits, enemies of public order! Austria herself uses the self-same terms to stigmatize those who resist oppression. I will notice one extract more, to which I would call the special attention of my readers. It is from one of the reports of the society in Lyons , which society had the principal management of American missions under Charles X. When this bigoted monarch was dethroned, and liberal principles reigned in France, the society so languished that Austria took the design more completely into her own hands, and through the Leopold Foundation she has the enterprise now under her more immediate guardianship.

“Our beloved king (Charles X.) has given the society his protection, and has enrolled his name as a subscriber. Our society has also made rapid progress in the neighboring states of Piedmont and Savoy. The pious rulers of those lands, and the chief ecclesiastics, have given it a friendly reception.”

Charles X., be it noticed, and the despotic rulers of Piedmont and Savoy, took a special interest in this American enterprise. The report goes on to say-

“Who can doubt that an institution which has a purely spiritual aim whose only object is the conversion of souls, desires nothing less than to make whole nations, on whom the light of faith has hitherto not shined, partakers of the knowledge of the gospel; an institution solemnly sanctioned by the supreme head of the church: which, as we have already remarked, enjoys the protection of our pious monarch, the support of archbishops and bishops; an institution established in a city under the inspection of officers, at whose head stands the great almoner, and which numbers among its members, men alike honorable for their rank in church and state; an institution of which his excellency the minister of church affairs, lately said, in his place in the Chamber of Deputies, that, independent of its purely spiritual design, IT WAS OF GREAT POLITICAL INTEREST.”

Observe that great pains are here taken to impress upon the public mind the purely spiritual aim, the purely spiritual design of the society, and yet one of the French ministers, in the Chamber of Deputies, states directly that it has another design, and that it was of “GREAT POLITICAL INTEREST.”-He gives some of these political objects-“because it planted the French name in distant countries, caused it, by the mild influence of our missionaries, to be loved and honored, and thus opened to our trade and industry useful channels,” &c. Now if some political effects are already avowed as intended to be produced by this society, and that too, immediately after reiterating its purely spiritual design, why may not that particular political effect be also intended, of far more importance to the interests of despotism, namely, the subversion of our Republican institutions?

Comments

FOREIGN CONSPIRACY AGAINST THE LIBERTIES OF THE UNITED STATES. CHAPTER VII — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>