The author of this book which was published in 1948, Jacopo Leone, was an Italian Roman Catholic who underwent training to become a Jesuit. He left the Jesuit Order after only a short time after seeing and hearing things that shocked him.

In putting forth a publication like the present, the authenticity of which will undoubtedly be strongly contested by those who are interested in so doing—one, moreover, which does not belong to the class of writings emanating from the Societary School, and which I edit in my own individual capacity, I am bound to accompany it with a testimonial, and with some personal explanations.

I.

I felt, indeed, that after all I was infinitely less competent to decide in the matter than those whose judgment upon it was opposed to mine, and that not having seen the documents or conversed with the witness, it would have been presumptuous and irrational in me to settle dogmatically that they were wrong and that I was right. I therefore suspended my judgment, and abstained from forming any positive opinion on the subject.

It was in Paris, towards the close of 1846, that I first saw M. Leone. I scarcely spoke to him about his manuscript, for which I was informed he had found a* publisher. I awaited the appearance of the work to become acquainted with its contents.

I must confess that at that time I did not believe much in the Jesuits, and therefore I was disposed to attach but little importance to the publication of the Conference. It had always struck me that the public did the Jesuits too much honour in giving themselves so much concern about them. I believed indeed that the order was deeply committed to very retrograde ideas, but I did not give it credit for the activity, profundity, or Machiavellian ubiquity generally imputed to it. In a word, to use a phrase that accurately expresses what I then thought, I calculated that at least a discount of from sixty to eighty per cent should be struck off from the current estimate respecting the Jesuits.

As for their obscurantist and retrograde conspiracy, I thought it of no more account against the development of human progress and liberty, than the barriers of sand raised by children against the tides of the ocean. And even now, though enlightened as to the character and intrinsic power of the celebrated Company, I still persist in that opinion; for, however strong the arms that raise it, the anti-democratic barrier is still but a rampart of shifting sand, incapable of stopping the rising tide: at most it can but trouble the clearness of the foremost waves.

II.

By-and-bye M. Leone was a more frequent attendant at our weekly conversations on Wednesday at the office of the Democratic Pacifique. He spoke to me of a work on which he was engaged, and appointed a day on which to read me a copious exposition of the argument. I listened to it with the liveliest interest, and was deeply impressed by its contents. They related to the publication of extremely important documents, stamped with the highest ecclesiastical sanction, absolutely authentic beyond all cavil (trivial objection), and formed to shatter the coarse and oppressive carapace (protective shell) of the Catholic Theocracy,* and place in the most shining light the democratic and humanitary Christianity of the gospel, and the fathers of the first three centuries. It is the lamp that sets fire to the bushel.

But to avoid every false interpretation of the word Theocracy, which occurs frequently in the preface, I declare that both therein, and in the rest of the work, it is employed in its historical signification, and not at all in its grand and beautiful etymological sense.

Theocracy, in its historical import is the usurpation of the temporal government by a caste or sacerdotal body, separated from the people, and exercising political, social, and religious despotism. For this Theocracy religion is but a means, domination is the end.

The etymological meaning of the same word is, on the contrary, the government of God, the coming of that reign of God, which Jesus commands us to pray for to our heavenly Father, and to establish amongst us; that is to say, the ideal of government here below—democracy, evangelically, harmoniously, and religiously organised. In this sense, far from repudiating Theocracy, no one would desire it more ardently than I!

The publication of this work, resting on the most solid bases, and of a theoretic value altogether superior, appeared to me most important. The Introduction was complete, and was about to be published separately in one volume, for which I was making the necessary corrections, when Leone received from one of our common friends in Geneva intelligence of a breach of confidence committed by his copyist, and the advertisement of the approaching publication of the Secret Plan in Berne.

On receiving this news, the details of which are given in the subsequent introduction, Leone changed his plans. He begged me to lay aside the first work, and immediately publish the Secret Plan in Paris, so as if possible to anticipate the necessarily faulty, truncated, and wholly unsubstantiated edition that was about to appear in Switzerland. But the notice he had received was too late, and ere long he had in his hands a copy of a bad edition, containing a part only of his MS., printed at Berne, without name or testimonial, and which in its anonymous garb—the livery of shame -—did not and could not obtain any general notice. Thenceforth Leone’s solicitude was not so much to hasten as to perfect the publication which was already in the press, and to make the third part (corroborative proofs), which is entirely wanting in the Berne edition, as complete as circumstances could require or allow.

III.

At that period there no longer remained any doubt in my mind as to the authenticity of the Secret Conference and Leone’s sincerity.

IV.

But the guarantees afforded by the character of the witness are not the only motives that have convinced me of the authenticity of his testimony. Thousands of proofs, incidents of conversation, questions put at long intervals on delicate points, and imperceptible circumstances of the drama, have always resulted in an agreement so exact, positive, and formal, that truth alone could produce such perfect coaptation (fitting together). One example will he sufficient to explain the nature of the proofs I am now alluding to.

Among other points in the narrative, it had struck me as an extraordinary and quite romantic circumstance, that, when the young neophyte entered the rector’s apartment in the convent of Chieri, and took for his amusement a book from one of the library shelves, he should have found in the very first instance, behind the very first book he laid his hand on, the registry of the Confessions of the Novices, and again, immediately behind it, that of the Confessions of Strangers, and the rest. I had often reflected on the singularly surprising nature of this chance, and I had intended to mention my perplexity on this subject to Leone. Now it happened one morning while I was writing, and while he was conversing near me with other persons to whom he was relating his adventure, I heard him say, in the course of a narrative delivered with all the precision of a very lively recollection, “I laid my hand on the first book on the library shelf.” This trivial detail, which was not in the first manuscript, and which Leone thus gave, unasked for, in the course of a recital the animation of which vividly recalled the scene to his memory and made him describe all its circumstances, explained to me in the most natural and satisfactory manner a thing which had previously appeared to me in the light, not indeed of an impossibility, but of a serious improbability.

This example is enough to show the nature of the counterproofs I have mentioned; and so great a number of similar ones have occurred to me, in the infinite turns and changes of conversation, during the four or five months I have been led to apply myself, often for several hours daily, to the correction of Leone’s manuscript and proofs, that for my own part, independently of the arguments drawn from the character of the man, they are enough to erase from my mind all doubt as to the veracity of his tale. The utmost skill in lying could not produce a tissue always perfectly smooth in its most delicate interruptions. Imagination may, no doubt, very ingeniously arrange the plot and details of a fiction; but if at long intervals, in the thousand turns of conversation, and without letting the author perceive your drift, you make him talk at random of all the details which the story suggests, then certainly if the web is spurious you will discover many a broken thread. Now, this web of Leone’s I have examined with a microscope for months together in every part, and I have not been able to detect in it one broken thread or one knot. I have no doubt, therefore, if the authenticity of the narrative become the subject of serious discussion, that the narrator will rise victorious over every difficulty that can be raised up against him; for I do not think that he can encounter any stronger or more numerous than I myself and some of my friends have directly or indirectly set before him.

V.

I will now examine considerations of a third kind, which have this advantage over the preceding ones, that they can be directly appreciated by everybody— for they are derived from internal evidence.

I say, without hesitation, that to me it is not matter of doubt that every cool impartial person, who has some experience of the affairs of life and of literature, and who shall have read very attentively the speeches in the Secret Conference, will recognize in them the distinct stamp of reality.

It seems evident to me that these speeches cannot be the produce of a literary artist’s imagination: the imitation of nature is not to be carried to such a pitch. Certainly, it is not a young man, a young Piedmontese priest, though endowed with talent, sensibility, imagination, and good sense, who could have produced such a work. To this day, though his intellect is much more mature and his acquirements considerably enlarged, I do not hesitate to declare Leone quite incapable of composing such a piece. I go further and assert, that there is not one among all the living writers of Europe who could hare been capable of doing so. There is in those speeches a mixture of strength, weakness, brilliancy, a variety of styles and views, a composite of puerilities, grandeur, ridiculous hopes, and audacious conceptions, such as no art could create.

Yes, they are surely priests who speak those speeches—not good and simple priests, but proud priests, versed in a profound policy, nurtured in the traditions of an order that regards itself as the citadel and soul of Catholic Theocracy—whose gigantic ambition, whose hopes and whose substance, it has gathered up and condensed; an order whose constant thought is a thought of universal sway, and which ceases not to strive after the possession of influences, positions, and consciences, by the audacious employment of every means. Yes, those who speak thus are indeed men detached from every social tie—emancipated from every obligation of ordinary morality—reckoning as nothing whatever is not the Order, in which they are blended like metals in the melting pot; the corporation, in which they are absorbed as rivers in the sea; the supreme end, to which they remorselessly sacrifice everything—having begun by sacrificing to it each his life, his soul, his free-will, his whole personality. Yes, those are truly the leaders of a mysterious formidable initiation—patient as the drop of water that wears down the rock—prosecuting in darkness its work of centuries over the whole globe—despising men, and founding its strength upon their weakness—covering its political encroachments under the veil of humility and the interests of Heaven—and weaving with invincible perseverance the meshes of the net with which, in the pride that is become its faith, its morals, and its religion, it dreams of enclosing Kings and Peoples, States and Churches, and all mankind.

History demonstrates that it is the nature of all great human forces, material or intellectual, military or religious, individual or corporate, to be incarnated in a People, an Order, an Idea, a Religion, or to have borne mere names of men, such as Alexander, Caesar, Mahomet, Charlemagne, Hildebrand, Napoleon, &c.; it is the nature of all these great forces to gravitate by virtue of their inward potency towards the conquest and unity of the world.

It is a phenomenon likewise proved by history, that hitherto the laws of ordinary morality—the duties considered by practical conscience as the imperative rules of men’s individual relations—are drowned and annihilated in the gulphs opened by those vast dominating ambitions, which substitute the calculations of their policy and the interests of their sovereign aim for the rules of vulgar conscience. At those heights in the subversive world in which humanity is still plunged, men are soon considered by those ambitions which work on nations and events, as but means or obstacles.

Now, the Theocratic genius, founding its domination on the alleged interests of God—covering them with the impenetrable veil of the Sanctuary—marching with the infinite resources acquired in a long practice of confession, in a profound study of the human heart, and in the arsenal of all the seductions of matter and mysticism; taking for the auxiliaries of its inimitable design human passions, obscurity, and time;—the Theocratic genius—if, with a deliberate consciousness of its aim, it has constituted itself a hierarchical militia, detached from all ties of affection—must necessarily carry to its maximum of concentration and energy that politic spirit before which persons and the morality of actions disappear, and which retains but one human sentiment and one moral principle—that of absolute devotedness to the animus (governing spirit) of the corporation, to its aim and its triumph. And who, then, save eight or ten of those strong heads among the higher class of the initiated—those politic priests, those brains without heart, puffed up by the defeat of the modern spirit (1824), intoxicated by a recent triumph, and by the perfume of that general Restoration which had already given them back a legal and canonical existence, and the favour of the governments of Italy, France, Austria, &c.—who but such men, taking measure at such a moment of their forces for conquest, could have held such language?

VI.

There are mad flights of pride so delirious, that no imagination could invent them. To set them forth with the fire, brilliancy, and energetic audacity, they display in a great number of passages in the Secret Conference, the Word that speaks must itself be wholly possessed by them. That somber and subterraneous profundity—that laborious patience, proof against the toil of ages—that sense of ubiquity—that absolute devotedness to a purpose whose fulfilment is seen through the vista of many generations—that absorption of the personal and transient individual in the corporate and permanent individual—and above all, if I may so express myself, that transcendent immorality, which all stamp upon the Secret Conference the character of a monstrous and insane grandeur; these are surely the tokens of a paroxysm (a sudden violent emotion or action) of subversive unitism, such as could only be manifested, the moment after a European resurrection and victory, by Policy and Theocracy allied in an Order self-constituted as the occult brain of the Church, and the predestined supreme government of the world.

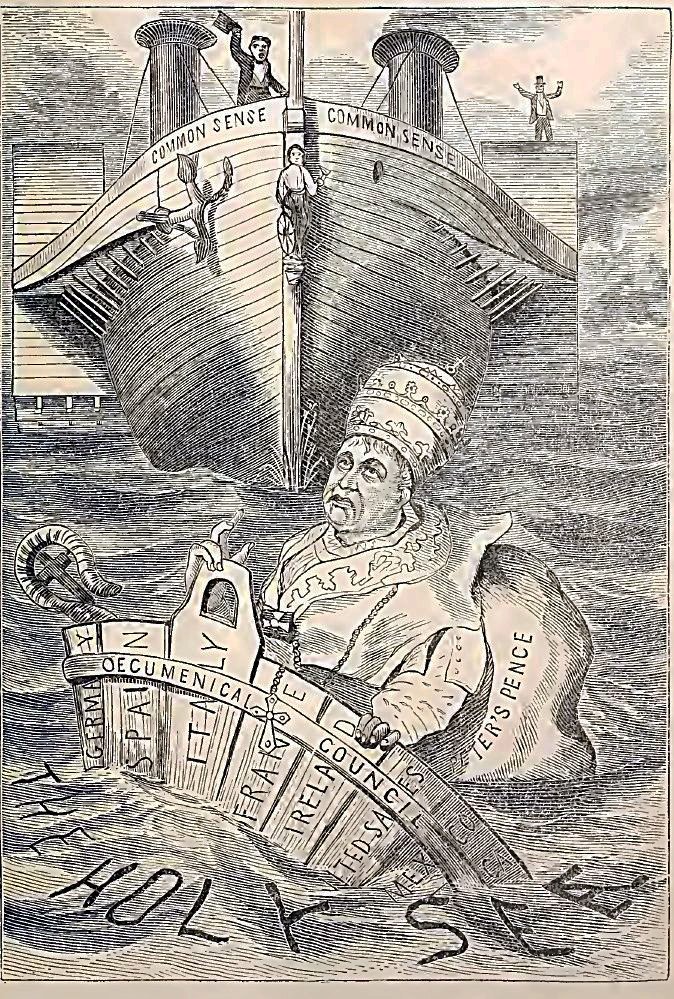

And truly, when we reflect on the organic virtue of that theocratic power, which feels itself immutable amidst the vacillations of the political world, we are constrained to own, that such is the nature of its means, such the temper of its weapons, that it might with more reason than any conqueror, or even than any people, aspire to universal dominion, if instead of seeking to cast back the nations into the past, and to plunge mankind again into the night of the middle ages, a thing which is purely impossible, it had undertaken the glorious task of guiding men towards the splendours of freedom and the future. That Order, which for many a century has braved kings and nations—which neither the decrees of princes, nor the bulls of popes, nor the anathemas of the conscience of nations, nor the terrible wrath of revolutions, have been able to crush—whose severed fragments reunite in the shade like those of the hydra (in Greek mythology, a many-header serpent or monster)—that Order, everywhere present and impalpable, which feels itself living, with its eternal and mute thought, in the midst of all that makes a noise and passes away—that Order, on comparing itself with those governments whose vices, corruption, and caducity (the quality of being transitory), would make them pliant subjects for its crafty magnetism—must certainly have conceived through its chiefs the plan developed in the Secret Conference, and none but the initiated could have given to that plan the profound, eloquent, and impassioned forms, which that grand folly there assumes. The fumes of pride have mounted to the brain of the mysterious colossus, and he has failed to perceive that his feet are of clay, and that the inevitable flood of the modern spirit is reaching them and washing them away.

Boundless ambition, a mighty organization, indomitable perseverance, and absolute devotedness, all directed to the attainment of an impossible object, an absurd chimera pursued by a transcendent system of means as immoral as they are puerile—such are, in brief, the characteristics of that modern incarnation of Theocracy which is called Jesuitism.

VII.

I am not the only person who has remarked a strange form that frequently recurs in the speeches of the reverend fathers of the Secret Conference, namely those harangues to imaginary auditors, of which they almost all present specimens, or fragments, in their addresses to their colleagues. There are some to whom this form seems extraordinary and unnatural. Extraordinary I own it is, but as to its being unnatural, the circumstances and the men considered, I am quite of the opposite opinion.

Men who for fifteen, twenty, or thirty years, more or less, have been in the daily practice of public speaking, whose incessant task is proselytism, the seduction of consciences, the propagation of their policy, the conquest of souls, and who when met together to concert and mutually make known their means of action and their modes of proceeding, are glad to display each his own individual skill, such men would naturally have recourse to the form of communication in question. On reflection, then, it is evident that this singularity is perfectly natural in the special case in which it occurs. The more improbable it seems in an abstract point of view, the more strongly does it argue in favour of the authenticity of the Conference; for most assuredly the idea of putting all those numerous harangues into the mouths of the reverend fathers would never have occurred spontaneously to one who should have sat down to compose a fiction. The thing is one of those which we can account for when they are done, but which we can hardly imagine beforehand. Leone himself has never, so far as I am aware, given the explanation of the matter which to me appears so simple. The answer I have heard him return to objections of this kind has always been, “I can only say that the thing was so.”

VIII.

It certainly cannot be said that there are not, in the preliminary narrative, or in the Conference itself, points as to which Leone has clearly perceived the difficulty of overcoming public incredulity. He has even debated with himself whether he should not suppress certain passages of the conference, knowing very well that they would prove stumbling-blocks, and that many persons refusing to believe them, might very probably reject all the rest along with them. Finally he resolved to set down everything he had heard with the most scrupulous fidelity, and in my opinion the has herein done wisely, notwithstanding the inconveniences resulting from such a course. Sound critics will see in the fact an additional evidence of truth. They will say to themselves that were Leone an author instead of a narrator, he would have taken good care not to leave in a work, not hastily put forth, matters which he must have been well aware would appear incredible.

IX.

I conclude with an observation. Leone gives with exact details the narrative of his own life at the periods which have reference to the event of which he speaks. It is incontestable that he entered the monastery of Chieri with an extremely ardent, fixed, and profound determination; that he desired nothing so much as to become a Jesuit; that hopes had already been held out to him which could not but have whetted his desires; and that all at once, without any ascertained motive, he was seen, to the great amazement of everybody, flying from that monastery into which he had so eagerly desired admittance two months before, and where he had met with nothing but kindness, favour, and all sorts of winning treatment. It is certain, then, that he received some terrible shock in the monastery. The fact is attested by his flight, his subsequent illness, and his sudden abandonment of that Jesuit career which had been so much the object of his ambition, while at the same time he did not quit the clerical profession. This mysterious revolution, the meaning of which he could not then explain to any one of his friends or relations, and of which his old mother, who now lives in Paris, did not know the cause until the death of the head of the family allowed Leone to quit Piedmont—this revolution was certainly the effect of some extraordinary and formidable adventure, some sudden revelation, some appalling burst of light; for him, whom it had befallen, it was decisive of the whole bent of his life, and made the study of all that pertains to Jesuitism thenceforth his principal occupation.

In fine, the facts relating to all the circumstances which form in the narrative the envelope, as it were, to the Secret Conference, are of public notoriety in Leone’s native land, and he narrates them publicly, mentioning names, places, dates, facts, and persons. Something most extraordinary, unknown to the Jesuits themselves, who were unable to account for his flight, must have perturbed his being, altered his health, and effected a total change in the bent of his mind and his ideas; and for my part I doubt not that the publication now made by Leone, is the true and sincere explanation of that mysterious point.

X.

I will now say a word as to my co-operation in Leone’s publication, because, independently of what I have already made known, there was in this matter a circumstance which has strongly corroborated my conviction.

Leone as yet writes French but very imperfectly, so that I have been obliged to revise his whole manuscript, pen in hand, before sending it to press. Now I found an enormous difference as to style between the second part and the others. In the Secret Conference Leone was supported by the text, and often by the solidity of the speeches, which he had only to translate, and here he left me hardly anything to correct; whenever there was any awkwardness or ambiguity of expression, I had only to turn to the Italian text and find a more exact translation for the passage. In this part of the work his French manuscript has only undergone slight modifications in a few passages.

In the other two parts (the first especially, for the third consists chiefly of extracts), I have had much more to do than I could have wished, and frequently whole pages to rewrite completely. The difference was so marked that it was impossible for me to retain the least doubt as to the duality of the sources whence it arose; and notwithstanding our conjoint labour, there still remains such a discrepancy between Leone’s style and that of the Secret Conference, that the least observant reader will easily recognize a diversity of origin. As an example, I will particularly invite attention to the reflection with which Leone closes the conference, and which begins thus (see end of the second part), “By these words, the echo and confirmation of others not less presumptous.” When we came to this passage in the course of our revision, Leone said to me, “Is it worth while, think you, to let that reflection stand?” “By all means, my dear friend,” I replied with a smile, “let it stand. We must not think of suppressing this precious naïf (French meaning naive) reflection with which you, as a narrator, have quite naturally closed your report of the conference. There is, if you will allow me to say so, between your summing up and that of the president, paragraphs xix. and xxi, which precedes it, so enormous, so colossal a difference, that I know no more glaring proof of the authenticity of the conference, and of the impossibility of your being its author. How pale and weak is what you say in comparison with the language of the general of the the Order! How much does the expression of your sentiments on Jesuit ambition sink below the Word of the Company, the living incarnation of that ambition? The contrast seems to me so important, that far from suppressing your lines, you must forthwith grant me permission to repeat to the reader what I have just been saying to you.”

And indeed whoever compares the grandiloquent language of paragraph xix. and the concluding words of paragraph xxi., with Leone’s final reflection, will, I think, admit with me that the latter is merely a narrator, and will own how far external passion if I may be allowed the expression, falls short of internal passion in the expression of a sentiment. To body forth the theocratic will and purpose with those traits of fire that flash every moment from the pen of De Maistre, and often from the lips of the fathers of the Secret Conference, the writer must himself have raised an altar to theocracy in his soul, and have long kept up, upon that inward altar, the somber fire its worship demands. Although it does not always show with equal brilliancy throughout the conference, every attentive critic will easily distinguish the language of the initiated from that of ordinary men.

XI.

Let me recapitulate.

In this affair I have examined the elements of the cause like a juror.

The character of the witness, my scrutiny into the circumstances of his story, and my study of the subject in itself, have left no doubt upon my mind as to the authenticity of the revelation, and I declare, on my soul and conscience, that I believe Leone TO BE PERFECTLY FAITHFUL AND SINCERE.

Now, whereas I should deem it odious to make use, even against Jesuitism, of fraud and calumny, I have held it no less obligatory upon me, in the actual state of things, convinced as I am of the reality of the Jesuit plan, to assist Leone, who had been unable to find a publisher, in laying it before the public. This seemed to me a personal and conscientious duty.

When I came to the determination to edit the manuscript, the Jesuits were exhibiting in Switzerland what they were capable of. They tried every means to bring about there an intervention of the anti-liberal powers—a coalition into which the French government monstrously entered. Instead of conjuring civil war by a voluntary retreat, those pretended disciples of Jesus were seen artfully kindling the fanaticism and rancour of the abused populations of the Sonderbund, and doing all in their power to provoke a bloody conflict. Their aim was to recover, by means of an intervention, the ground taken from them in the cantons and the diet by the progress of free ideas. They spared no effort to produce that odious result, which happily they failed to accomplish.

Moreover, it is well known what has been and what is still the part played by them in Rome, and what a weighty obstacle they are to the liberal intentions of the great Pontiff, who at every step in advance encounters their occult and potent influence. The publication of the Secret Plan will serve to unmask them. Their whole strength consists in the mystery in which they shroud themselves; let their projects be exposed to daylight, and the charm will be broken. These darksome and malignant associations are like the phantoms of the night that vanish the moment they are touched by one ray of sunshine.

I have said wherefore, and how, I came to take upon me the editing of this book, although certain of Leone’s tendencies are not always perfectly in accordance with mine. The main thing for me in this matter has been to aid in unveiling that odious conspiracy (in which many still hesitate to believe, and I own that I was for a long time among the number) which has for its defined and specific end the re-establishment of darkness and despotism, and for its means the deliberate and conscious employment of the most abominable of lies—religious lying.

Catholicism is a great religious institution. It is necessary to the development of that living institution that the hierarchy which governs it be renovated and retempered in the living sources of the gospel The first steps which the pontiff, who now wears the tiara, has made in the way of progress and liberty, are a capital revelation for Catholicism. To be or not to be.

Christianity is immortal. A religion which is summed up in these words, “Love one another, and love God above all things,” cannot die out from mankind; for every progress of humanity is but a new and fuller unfolding within it of Christianity, that is to say of love and liberty. But the future destiny of the catholic institution, which is a government, now depends, like that of all other governments, on its reconciliation with the spirit of the gospel, which is the spirit of humanity.

The catholic government is still aristocratic and despotic. Let it emancipate its serfs! let it recognize the rights of the secondary clergy and guarantee them; let it put itself in harmony with the sentiments of the primitive church, and strive to free the world of employing itself in the old work of oppression. Christianity is young and radiant; Theocracy is decrepid: let Roman Catholicism choose between the two. Any long delay would be perilous.

The Jesuits are the janissaries of theocratic Catholicism. The pope of Islam has perhaps shown the Catholic pope in what way a serious reform should be begun.

LONDON, Jan. 27th, 1848.

P.S.—Paris, May 28th, 1848.—Since I wrote the above Preface to Leone’s narrative in London, and at the moment when the work was about to appear simultaneously in England, France, Belgium, and Germany, the Revolution of February changed the face of things. The party of oppression, favoured by the impious alliance of the French government with the absolute courts, has been miraculously overthrown; the Jesuits themselves have been expelled from Rome.

Let us not be deceived, however; the battle is not won; peace and liberty are still far from being solidly established in the world.

Peace, liberty, complete reciprocity (solidarity) and universal brotherhood, will only be realised by the definitive incarnation of the spirit of the Gospel in humanity. The work now before us is to make a democratic and Christian Europe, instead of the aristocratic and, socially speaking, heathen Europe, which was yesterday official and legal. The question is far more religious and social than political. It is the era of practical Christianity which we are called on to inaugurate.

Hence, though Leone’s publication now no longer possesses the character it would have had in the very heat of the strife, before the Revolution, it nevertheless retains its value. It will serve the good cause by exposing the designs of the bad cause; it will help the development of the true Christianity, democratic Christianity, by exhibiting in its odious nakedness the pseudo Christianity, the Christianity of the profit-seekers, of Theocracy, of Despotism.

The two parties must be accurately segregated: on the one side daylight, on the other darkness.

The subordinate clergy, whose condition in France is an actual civil, political, and religious thraldom (the state of servitude or submission), has respired the air of freedom with hope and love. Let the Republic give it a democratic constitution—let it restore to it the rights and guarantees of which it cannot be much longer despoiled—and it will soon have made its conquest. The subordinate clergy begs only to be released from the yoke. It groans beneath superiors who are imposed upon it, and whom it fears; whereas it ought to elect and love them. Let us emancipate the sacerdotal people; set it free, and the oppressive and shameful doctrines of Jesuitism will find in it their most formidable antagonist.

It is time that this be done. It is time that the ecclesiastical people communicate with the lay people in the sentiments of modern life and modern ideas. It is idle now to think of conserving dead interpretations. Society is athirst for liberty, equality, and fraternity: it is time to return to the holy source, and recover the liberating import of Christianity.

Providence had committed an august mission to the Church: to perpetuate Christ’s teaching, to render Him for ever living on earth, preciously to preserve and to realise daily more and more the gospel principles of unity, charity, and universal brotherhood. Instead of accomplishing this task, the theocratic spirit has striven to efface from the Church the traces of Him who had founded it—to filch away the liberal meaning of his instructions—to paralyze the intellectual life— and, in a word, to make mankind a flock of brutes, to be shorn by the Princes of the Church and the Princes of the World.

Disowned, let us hope, by the mass of the clergy, this theocratic spirit will soon be constrained, finally and for ever, to give up Europe to the genius of the new times, reconciled with the most sacred traditions of humanity. The moment is come for the Church to repudiate all fellowship with a sect which has led it astray from its proper path, and to regain the ground it has lost in the confidence of men, by actively furthering all truly Christian works—that is to say, all works of social and intellectual amelioration (improvement).

The Revolution of February has opened a magnificent field for the Church; the problem now to be solved is the CONSTITUTION OF A CHRISTIAN SOCIETY. For eighteen hundred years has Christianity been preached to men;—how to incarnate it in society is now the problem. Political society itself invokes the Gospel formula, taking for its motto those three Christian words, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity! Let the subordinate clergy and the liberal bishops, casting off the anti-christian and anti-catholic traditions of Jesuitism, press forward, full of faith, hope, and love, in the path which is opened to them. The mission of true Christianity is now to found universal Democracy.

The Pope has expelled the Jesuits. It remains for him to reinstal the Papacy in its spiritual and catholic functions by abdicating all temporal authority. It is its temporal interests that have corrupted the Church. So long as the head of the Church shall remain King of the Roman States, the Catholic Church will be nothing but a Roman oligarchy. It must again become a spiritual and universal democracy; and its general councils must proclaim to the earth the true sense, the liberating and emancipating sense, of the Scriptures.

A sincere return to the democratic spirit of the Gospel; a rupture of that simoniacal (the act of selling church offices and roles or sacred things) alliance which odiously perverted a religion of freedom and fraternity, making it into a yoke of oppression for the benefit of all who use up nations for their own profit; a formal repudiation of the feudal, theocratic, obscurantist, and Jesuitical spirit: such is the price at which the salvation of the catholic institution is to be secured.

V. C.

PP.S. July 10th, 1848.—Events follow upon each other with such rapidity that every day produces in a manner a new situation.

The day after the Revolution of February, the Republic was accepted by all in France. Louis Philippe left behind him neither affection nor esteem, nor roots of any sort. Rejoicing in his fall, the legitimists said to themselves that the time of monarchies was passed, and gave in their adhesion on all sides to the republican principle, the government of all, by all, and for all.

The grand and vast idea of universal union found in the language of Lamartine an utterance full of brilliancy, elevation, and authority.

Unfortunately, narrow categories, language of injudicious violence, and conquerors’ airs, calculated to lead to the belief that the immense majority of the French citizens, who were republicans of the morrow, were about to be governed as conquered populations by the republicans of the eve; all those violences of speech and demeanour, which had not even the logic of the strong hand in their favour, produced serious reactionary ferments in the country. The huge folly of postponing the elections considerably diminished the democratic element in the National Assembly, which instead of feeling itself united, confident, and strong, was from the very outset uncertain, distrustful of itself, irresolute, and divided.

Hence the critical situation in which we now behold the republic and society.

A deliberately reactionary party, which would not have existed, had not its creation and development been provoked as if on purpose, is rapidly organising. It is turning to its own account material interests, the nature of which it is to be blind, blind and violent egotisms, and the resuscitated hopes, enterprising and intriguing, of the various dynastic factions and of the theocratic faction.

All these elements constitute a formidable coalition, in which intrigue is organising the resistance of those interests which it can so easily mislead and impassion.

The Jesuit element, that mysterious army at the service of obscurantism, despotism, and social retro-gradation, has thus suddenly found allies in those who but yesterday fought against it.

Under the restoration it had on its side in France only the party of the emigration.

Under the monarchy of July it had indeed enlisted among its allies the official and satisfied bourgeoisie, which entered into covenant with it in its retrograde tendencies. M. Guizot and his rotten majority supported the general tendencies of Jesuitism, and formally yoked themselves to its cause, by pledging the policy of France to the service of the Sonderbund.

Today, a new stratum of French society has passed over to the enemy, to the fear of progress and of democratic and social principles—a stupid and fatal fear, for interests can only be saved by their alliance with sentiments and principles. This new retrogression is authenticated by this token, that M. Thiers—who is what is called a tactician, a practical man, a man of manoeuvres—and his organ the Contitutionnel, have, with brazen fronts, gone over to the party of which they had long been the bugbears.

M. Thiers, moreover, maintained a few days ago, in a committee of the Assembly, amidst the applause of many liberals of yesterday (liberals now entrusted with the task of founding the democratic republic), “that it was very dangerous to develop the instruction of the people, because instruction led infallibly to communism.”

The anti-democratic coalition is bound up with the National Assembly, and the compact is signed between all the parties of the past.

Out of doors the movement is being organised by the insidious arts employed to terrify and blind the most legitimate interests.

Furthermore, the re-actionists will rapidly use up all the men of the revolution; then, when the industrial and commercial crisis shall have passed away, they will again repossess themselves of the powers of the state, and with the help of all the confederated enemies of liberty and progress, they will re-establish society on its Old Principles, “the mischievous nature of the new principles being definitively proved by the evils which their invasion has for sixty years let loose on the modern world.”

That is the plan.

It is a general coalition of all fears, all egotisms, and all intrigues, against the legitimate and regular development of democracy.

This is literally the very same purpose as that aimed at by the Company of Jesus; accordingly, the alliance has been already concluded with the political representatives of the Company.

V. C.

I.

There is no one but has devoted some attention to the reappearance of the too famous Company of Jesus on the European stage. Many have rejoiced at the event; a greater number have beheld it with deep sorrow or irritation.

To say the truth, there were various reasons why a fact of this nature should interest governments and nations; for if ever the aim of that audacious Order could be achieved, every right and every liberty would be at an end. I do not think I exaggerate in expressing myself thus; on the contrary, I am strongly persuaded that those who read the disclosures made in this work will share my opinion.

Let me be permitted, in the first place, to enter into certain personal details, before I proceed to initiate the public into the secret I am about to divulge. I will be as brief as possible.

In 1838, I voluntarily quitted Piedmont, my native country, went to Switzerland, and settled in Geneva. At that period nothing yet presaged the ascendancy which the Jesuits were soon to obtain in the affairs of that republic, and the troubles in which their intrigues were to involve various other parts of Europe. Yet I did not hesitate to say openly to a great number of persons what there was to be apprehended in that way. I was not believed. My predictions were universally regarded as dreams. In vain I repeated to them that I possessed proofs of the invisible snares and most secret projects of the Company. A contemptuous smile was the answer to my words.

Gradually the face of events was changed, and the first symptoms of the Jesuit influence began to show themselves in Prussia.

Every one knows the commotion caused by the question of mixed marriages raised by the Archbishop of Cologne, and his ultramontane pretensions. A powerful party, and celebrated writers, Gorres among the rest, declared themselves the prelate’s supporters, and undertook the defence of doctrines which had long been considered dead. At the same period, pompous announcements were made of the conversion of princes and princesses, high personages of all kinds, learned men and artists. Such events were talked of with amazement in every company.

I happened to be one evening at the house of Mr. Hare, an Anglican clergyman, when a number of distinguished foreigners were present. The conversation ran exclusively upon the subject of these brilliant conquests, and everybody strove to invent some hypothesis on which to explain them. From what was stated of several of the converts by those who knew them personally, it was inferred that the real motive of their change was not precisely of a religious nature. I declared that the conjecture was not erroneous; and I was thus led to lay before the company present the course of circumstances through which I had become in a manner an initiated Jesuit.

A person who took part in the conversation, and who was travelling under the title of count, expressed a strong desire to see some portion of the Secret Plan, which had been mentioned. At his request, I called on him next day, and read him certain pages of the manuscript. He listened with great attention, seemed very much struck by some passages, and owned to me that at last he could explain to himself many enigmas. He asked me to let him keep the manuscript for a day, in order that he might study it more at leisure. This I declined; and then he made known his name. He was a prince nearly related to the royal house of Prussia. I persisted, nevertheless, in my refusal, though he offered me his support, and even made me some tempting promises.

The prince, somewhat to my surprise, requested me to give him a French version of the Secret Plan, that he might, as he said, have it translated into German. He recommended me to observe the greatest discretion, and insisted that I should not compromise his name. I was to deal only with his son’s tutor on the subject. Furthermore, it was arranged that I should subjoin an essay on the question pending between the cabinet of Prussia and the Holy See, wherein I was to demonstrate that the attempts made by various prelates, especially their attacks upon the university system of education, and their growing audacity in enforcing the old maxims of Rome, were not a purely local and fortuitous manifestation, but a fact closely connected with a vast conspiracy, pregnant with danger to all the powers.

I set to work, and wrote an account of all the strange incidents through which I had become an invisible witness of the occult committee in which the Jesuit plot was concocted. As soon as I had finished the translation of the plan itself, which I sent off by installments, and just as I was about to enter on the conclusion, I was desired to stop short—the pretext alleged being the death of the King of Prussia, which had just occurred. I had even a good deal of trouble to recover the copy I had sent.

I was soon surrounded with people who obtruded their advice upon me; telling me, that if aid was not afforded, me towards publishing, it was for my own sake it was withheld; that I ought to beware how I braved a society known to be implacable—a society that had smitten kings. “Who are you,” they said to me, “to cope with such a power, and not fear its numerous satellites?” Then, gliding into another order of considerations, they would say, “Nothing can be more dangerous than to initiate the people into such mysteries. It is enough that they should be known to those whose position authorises and enjoins them to frustrate an ambition, which is the more enterprising and mischievous inasmuch as religion and blind multitudes serve it as auxiliaries.”

These observations would have had less influence over me, had they not derived weight from the increasing anxieties of an aged and timid mother. Besides, my existence then depended on families who would have been deeply offended by a publication of such a nature. All this embarrassed my projects; and eager as I had been on my arrival to send the Secret Plan of the Jesuits to press, my many disappointments led me to postpone its publication indefinitely, though I could not conceal my disgust and despondency.

During all this time the influence of the Jesuits had augmented, and the liberals were beginning to regard it with apprehension. People came to me with all sorts of solicitations; and so, notwithstanding my many disappointments, I was constrained, in a manner, by events and entreaties, again to make ready for the press this long-retarded work.

But other obstacles again delayed it, for everything seemed to conspire against an enterprise for which, in a great measure, I had voluntarily expatriated myself. The persons with whom I had come in contact for this business sought only their own interest, and wished to place me in such a position as would have entailed on me all the annoyances and dangers of the publication without any of its advantages.

The Genevese government increased my perplexities by its persecutions. That government of doctrinaires, or Protestant Jesuits, so deservedly overthrown last year, conducted itself on narrow, egotistical principles, and was particularly captious towards strangers. I was several times summoned before its police on the most futile pretexts. Unable to prove anything against me, they took upon them to judge my intentions; interpreted my religious and democratic ideas as a crime, and strove to intimidate me with threats of dire calamities. On my part I ventured to predict for that intolerable government a speedy and ignominious fall. At last I was ordered to quit the country within the briefest space of time, without any cause being assigned to justify that arbitrary measure. Thus a final stop was put in Switzerland to the publication of my work, which had already been rendered so difficult by all the obstacles I have mentioned.

II.

When I came to Paris in 1846 I had no thought of making fresh attempts, more especially as I was told I should have great difficulty in finding a publisher. I applied myself to the composition of a work, now in a great measure completed, founded on documents of unquestionable authenticity, and which I should even have wished to print before the Secret Plan, as fitted in every respect, by its important revelations, to secure to the latter the most solid basis in public opinion. But when I was about to publish it, I received from Geneva a letter informing me of a monstrous abuse of confidence. The person I had employed to transcribe my manuscript of the Secret Plan had copied it in duplicate. He had put the second copy into the hands of a society, which, strange to say, had been formed for the express purpose of trafficking in this robbery. The excuse they offered was, that since I had during so many years divulged the secret plan of the Jesuits, the thing had become the property of the public. Moreover, as I had transcribed it surreptitiously, it did not belong to me, but was free to be used by anybody. It will scarcely be believed that the spoiler even went so far as to dictate the terms of a bargain to the despoiled, and to add irony to impudence, since the work had been printed several days before in Berne, as witness a copy sent me. The insolent letter he wrote me deserves to be known.*

“Geneva, Sept. 7, 1847.

“Sir,

“After having so long played with us, it is extremely surprising that you now protest against the publication of a work containing essentially the disclosure of speeches captured without permission by your ears, or rather by your eyes, in 1824.

“This protest is the more astonishing after your having yourself communicated those speeches to hundreds of persons, so as to make them be regarded as common property.

“Though I consider your protest as insignificant, and as a thing which at most can only result in giving you trouble and making you spend money uselessly, yet on the other hand, since my object has been attained, and since it is from public motives and not for any private interest that I have done so, I now offer to treat with you on the following terms:—In case you desire to become the proprietor of this publication, I consent thereto, on condition that you immediately furnish the necessary securities for the complete payment of the printer and of the incidental expenses. I have the honour to salute you.

F. Roessinger.

What! The very persons who profess themselves such uncompromising enemies of the Jesuits, do not themselves refuse to act on the maxim that “the end justifies the means.” But what has been the result of their spoliation? That it has been of no manner of advantage to them. What confidence, indeed, would there be in a paltry pamphlet, without name or warrant for its authenticity? The work, too, they published was but a shapeless abortion, a rough draft of a translation, very imperfectly collated with the original, and what is worse, truncated, slovenly, incorrect, and swarming with mistakes. The edition I put forth is rigorously exact and scrupulous; I have long and minutely scrutinized it, and it has been re-corrected under the eye of guides who have helped me to convey in French the full force of the original, which is often hard to translate. I have subjoined (added) to the Secret Plan elucidations (clarifications) of great importance, and I have related the circumstances through which it has come into my possession. Finally, I have brought forward counter-proofs of various kinds, all drawn from authentic sources, in support of the essential views and ideas developed in the plan.

The publication put forth by my spoliators (robbers) is the more blamable, inasmuch as the manner of its execution has been such as to compromise the fundamental document. For, I repeat, what authority can it have without my co-operation, without my name, and the corroborative proofs that accompany it in the present volume? Is it not a culpable and shameful act to put in jeopardy a matter of such moment? If they were actuated by no sordid motives, why did they not apply to me, and offer me the means of giving publicity to my manuscript in the way necessary to secure its full effect? In acting with such bad faith, did they not expose themselves to see the blow they designed for Jesuitism turned back upon them to their confusion? What was to prevent me from annihilating the result of their manoeuvre? Was it not in my power utterly to discredit the story, by attributing it to a freak of my youth?

I will say more. What they have done has put me in a position, from which it rested only with myself to derive profit, by proving by letters, ante-dated a few years, that my design had been to play off a hoax.

III.

Those who have at all reflected on the Order of the Jesuits, who have studied its history, and have had a near view of its workings, will by no means be surprised at its profound artifices and superb hopes. Do we not see it at this moment in France become the guide of the bishops, and giving law to the inferior clergy. M. Henri Martin thus expresses himself in a remarkable work recently published:

“The clergy, in its collective action, is little more than a machine of forty thousand arms, impelled by its leaders against whomsoever they please, and those leaders themselves are pushed forward by the Jesuit and neo-catholic congregations.”*

* De la France, de son Genie et de ses Destinies. Paris, 1847, p. 92.

Well-informed clergymen have assured me that the Jesuits were never so well seconded and supported as they now are. The establishments dependent on them are very numerous, and increase daily. Their resources are prodigious. A letter addressed to the Siecle thus speaks of their progress. Such a letter serves well to corroborate what is contained in the Secret Plan. I will quote the greater part of it:—*

* December 17, 1847.

“The hill of Fourvieres, which commands Lyons, on the right bank of the Saone, is a sort of entrenched camp, wherein all the bodies of the clerical militia are echelonned, one above the other, in the strongest positions; thence they hold the town in check, like those formidable fortresses which have been built to intimidate rather than to defend it. The long avenues that lead to Fourvieres and the chapel that surmounts it, are thronged with images of saints and ex voto; and but for that industrious city which unfolds its moving panorama below your feet, you might fancy yourself in the midst of the middle ages, and take its factory chimneys for convent spires.

“The exact statistics of the religious establishments of Lyons, with the number of their inhabitants and the revenues they command, would form a very curious book; but the archbishopric, which possesses all the elements of those statistics, is by no means disposed to publish them. The clergy, since the severe lessons given it by the July event, likes better to be than to appear; its force, disseminated all over France, and not the less real because they do not show themselves; and it can at any moment, as occasion may arise, set in motion that huge lever, the extremity of which is everywhere, and the fulcrum at Rome.

“Now, the soul of this great clerical conspiracy, the vital principle that animates it, is the Jesuits. Every one knows the well-grounded dislike with which this able and dangerous order is regarded from one end of Europe to the other. Yet it must be owned that in it alone resides all the life of Catholicism at this day; and the clergy would be very ungrateful if they did not accept these useful auxiliaries even while they fear them.

“All France knows that famous house in the Rue Sala in Lyons, one of the most important centres of Jesuitism. At the period of the pretended dispersion of the order, that great diplomatic victory in which M. le Comte Rossi won his ambassador’s spurs, the house in the Rue Sala, as well as that in the Rue des Postes in Paris, dispersed its inmates for a while, either into the neighbouring dioceses, as aide-de-camps to the bishops, or as tutors in some noble houses of the Place Bellecour; but when once the farce was played out, things returned very quietly to their old course, and the Rue Sala, at the moment I write, is still with the archbishopric the most active centre of politico-religious direction.

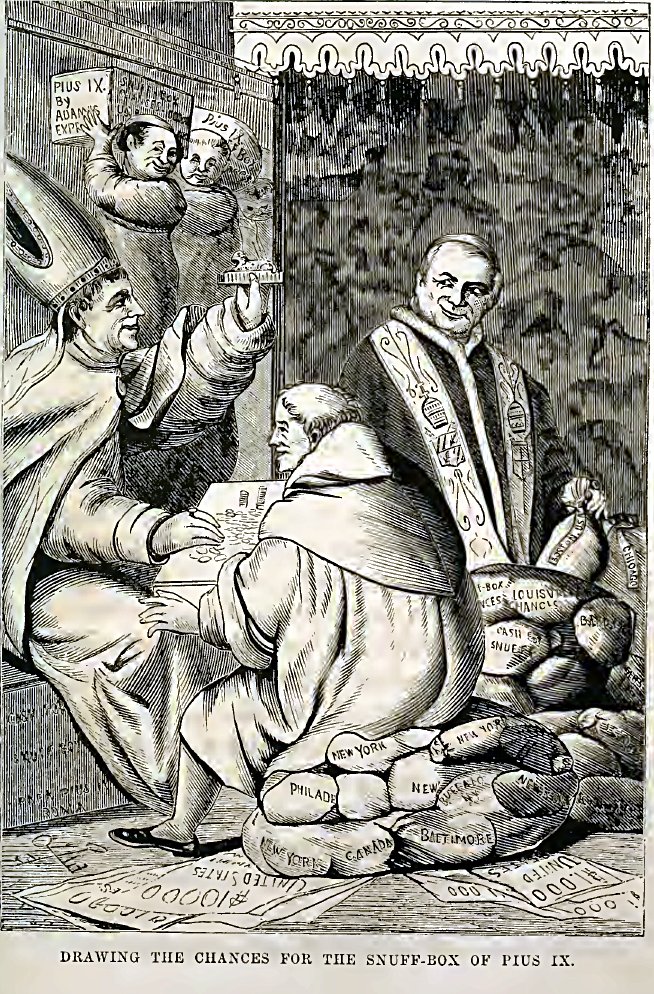

“That activity is principally directed upon two points; by means of the brotherhoods (confreries) it reaches the lower classes, whom the clergy drills and holds obedient to it; by education it gets hold of the middle classes, and thus secures to itself the future by casting almost a whole generation in the clerical mould. Let us begin with the brotherhoods. We will say nothing of those that are not essentially Lyonnese, and whose centre is elsewhere, though they possess hosts of affiliated dependents here. We will merely mention by name the Society for the Propagation of the Faith, whose centre, next after Rome, is Lyons, and which alone possesses a revenue of four millions and a half of francs. But the most important, the one which draws its recruits most directly from this industrious population, is the Society of St. Francis Xavier. Its name sufficiently indicates to what order it belongs; it is Jesuitism put within the reach of the labouring classes, and you may recognize it by the cleverness of its arrangements. The workmen, of which it consists almost exclusively, are disposed in sections of tens, hundreds, and thousands, with leaders to each section. The avowed purpose of the society is to succour invalid workmen, who, for a subscription of five sous a-month, or three francs a-year, are insured medical aid and twenty-five sous a-day in sickness. Such are the outward rules of the society; but in reality its design is clerical and legitimist: the two influences are here blended together in one common aim.

“Another and perhaps more dangerous means of action is the vast boarding-school which the brethren of the Christian schools, under the supreme control of the Rue Sala, have established at Fouvrieres. This gigantic establishment, which can accommodate upwards of four hundred interns, was founded about eight years ago in defiance of all the universitary laws. Its object, which is distinct from that of the small seminaries, is to give young men of the middle and inferior trading classes a sort of professional education, comprising, with the exception of the dead languages, all the branches taught in colleges. The complete course of study embraces no less than eight years. In this institution, as in all others of its kind, the domestic arrangements are excellent, and the instruction indifferent, being imparted by the brethren. Masters, fit only to teach little children their catechism, instruct adults in the highest branches of rhetoric, philosophy, and the physical and mathematical sciences. In consequence, too, of the continual removes of each of the brethren of the doctrine to and from all parts of France, any able professors who may have been formed in Lyons are soon appointed directors in some other town; and the system of teaching in the institution, however high in appearance, does not in reality rise above a very humble level.

“The annual charge is as low as possible, not exceeding 550 francs, which barely covers the indispensable expenses. This low rate of charge, aided by the all-potent influence of the confessional over mothers of families, attracts to the institution multitudes of lads of the middle class. As for the children of the poor, they belong of right to the schools of the doctrine— the primitive destination of the order, and one in which it can render real services. But this is not all: one of the centres of the Christian schools being placed at Lyons, there was requisite a noviciate house; and the order has just procured one, by purchasing for 250,000 francs a magnificent property at Calvire, within a league of Lyons. The vendor allowed ten years for the discharge of the purchase money; but the whole was paid within eighteen months; and a vast edifice, capable, when complete, of accommodating more than four hundred resident pupils, has risen out of the earth as if by enchantment. The estimate made by the engineer who directed the works, and who is a member of the society, amounted, it is said, to a million and a half of francs, and it has been exceeded.

“As for the lesser seminaries, of which there are many in the diocese, we will only mention that of Argentine, which contains five hundred pupils, and that of Meximieux, which has two hundred. Hence we may form an approximate idea of the immense action on education exercised in these parts by the clergy, in flagrant contravention of the university laws and regulations. The low charges of their institutions, not to mention many supplementary burses, give it the additional attraction of cheapness; and for those very low charges (about 400 francs) the Jesuit schools are supposed to afford their pupils instruction in all those branches of knowledge, Greek and Latin included, which are taught in those gulphs (archaic variant of gulf) of perdition which are called Colleges.

“On the whole, we may reckon at the number of one hundred the religious establishments intended whether for the education of both sexes, or for the relief of the distressed. All the suburbs of Lyons have their nunneries; and monastic garbs of every form and colour swarm in the streets. The Capuchins, however, who were formerly found there, have migrated to Villeurbonne; and the Jesuits, jealous of any rivals of their supremacy here, are said to have purchased their retirement at the cost of 900,000 francs.

“If you are astonished at the immense sums which the clergy here dispose of, recollect that one individual, Mademoiselle de Labalmondiere, the last scion of a noble family, has left the church a sum of ten millions, of which the archbishop has been named supreme dispenser. Through the confession, by means of the women, and by all kinds of influence direct and indirect, the clergy keeps the whole male population in a state of obsession and blockade. A trader who should revolt against this influence would instantly provoke against him the whole clerical host, and would be stripped of his credit and put under a sort of moral interdiction that would end in his ruin. The university, which possesses at Lyons some distinguished men, a brilliant faculty, and an excellent royal college, is put in the archiepiscopal index; and what here as elsewhere is called freedom of teaching, that is to say the power of taking education entirely out of lay hands and committing it to corporations, is the object of all the prayers of pious souls here, and of all the combined efforts of the archbishopric and the Rue Sala.”

IV.

The Jesuits have shown themselves in their true colours in Switzerland, where, merciless as ever, they chose rather to provoke the horrors of civil war than to yield, as the Christian spirit enjoined them. They have thereby augmented the hatred and contempt with which they are regarded on all sides. So sure were they of victory, that in their infatuation they disdained to take the most ordinary precautions.

“Apropos of the Jesuits,” said the Swiss correspondent of the National at that period, “it will be well to give you some account of the documents which most deeply compromised the reverend fathers and their allies both in Switzerland and in other countries. It will be seen whether or not the presence of the order is extremely dangerous to the countries that afford them an asylum.

“In the first place, there has been discovered at Fribourg a catalogue in Latin of all the establishments which the Jesuits possess in a portion of France and Switzerland, with a list and the addresses of all the persons connected with them. I have sent you two numbers of a Swiss journal in which there is an abstract of this catalogue, drawn up with the greatest care. You will perceive from it that the Jesuits’ houses have greatly augmented in number in France, since the pope made a show of promising M. Rossi and M. Guizot that they should have no more establishments in your country. The chambers will see how their demands have been derided. France will learn how she is duped, and what is the occult power that rules the government. For proof of all this, I refer to the analysis of the famous catalogue, which you will not fail to publish.

“There are two other documents, which you can see in the Helvetie of Dec. 18. The first is an address of two Fribourg magistrates, the president of the old great council, and a councilor of state, who humbly prostrating themselves at the feet of the Holy Father, recommend M. Marilley for bishop of the diocese, carefully insisting on the feet that he is most favourable to the order of the Jesuits. Now that prelate, a consummate hypocrite, had been at war with the society, and gave himself out for a liberal.

“The other document is still more curious and instructive. It is an address from the deaconry of Romont (Canton of Fribourg) to the apostolic nuncio at Lucerne, dated Dec. 20, 1845, and recommending the same Marilley, a parish priest expelled from Geneva, to the pope’s choice as bishop. The clergy of the deaconry, labouring hard to refute one by one the calumnious accusations directed against their protege, prove that M. Marilley by no means deserves the epithet of liberal; that he is not even a little liberal; and that far from being hostile to the reverend Jesuit fathers, he has given them authentic testimonies of his special veneration and esteem. The most remarkable passages of the address from the deaconry of Romont are those relating to politics. Speaking of the Catholic association, of which, like almost all the clergy of the diocese, M. Marilley was a member, his protectors say, ‘In 1837 this association wrested by its influence the majority in the grand council from the radicals, who were threatening among other things to dismiss the reverend Jesuit fathers from the canton. So the conservatives owe to this calumniated association their majority and their places, and the reverend Jesuit fathers owe to it their actual existence in Fribourg.’

“Further on, with respect to the old doctrinaire conservative government of Geneva, the address says, ‘Geneva does not choose to be either frankly conservative, because it is Protestant, or openly radical, because its votes are swayed by its material interests, and by the potent suggestions of Sardinia and France.’ Other passages manifest the close alliance of the Jesuits and of the conservatives, both protestant and catholic.

“A fourth document is the report of an inquiry made in Fribourg by order of the provincial government as to the reality of an alleged miracle attributed to the Virgin Mary. A priest and other witnesses had deposed that a soldier of the landsturm, who wore one of those medals of the Immaculate Virgin of which I have told you, had been preserved, on the night of Dec. 7, from the effect of a ball which had struck him on the spot covered by the medal The whole is attested by Bishop Etienne Marilley. Now the inquiry has rendered the imposture clear and palpable; the knavery of the bishop, the priests, and the Jesuits is laid bare. The matter of this inquiry will assuredly acquire great publicity.

“The Valais is not less rich in revelations than Fribourg and Lucerne. The federal representatives have in their hands all the official documents and the correspondences respecting the Sonderbund and the late military events, among others an authentic deed proving that Austria made the League the present of three thousand muskets which you know of. These documents contain proof that the League was a European affair, and that the purpose was*to establish in Switzerland the forces of ultramontanism and the centre of re-action; that what was designed was not an accidental association, and a defence merely against the attacks of the free corps, but a permanent League, and a dissolution of the Confederation in order to the reconstruction of another which should be recognized, supported, and ruled by foreign diplomacy.

“We have not exhausted the stock of documents. Fresh ones are discovered every day.”

V.

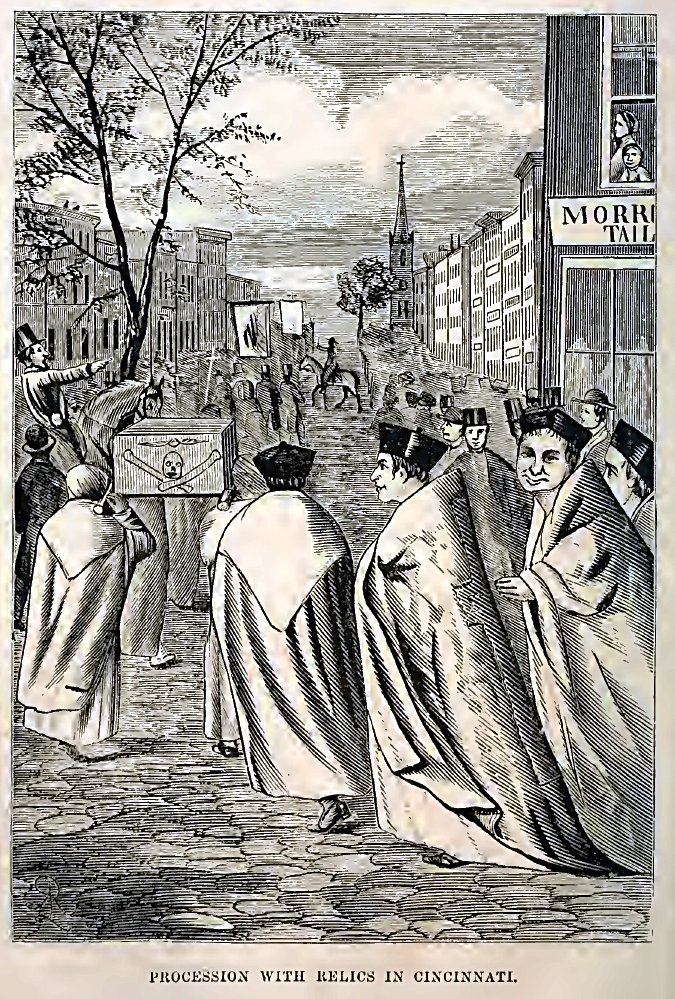

Enough so far to raise a corner of the veil. The plot is seen in action just as it is laid down in the Secret Plan, with which the reader is about to be acquainted. Its scope, we perceive, is formidable. Every means is welcome to its concocters that can forward their success. Their journals, especially the Univers, strangely mistaking the age, have promulgated plenty of miracles to sanctify the cause of the Jesuits in July. Their abominable fraud has not been able to remain concealed; the press holds up its perpetrators to contempt. Here then we have it proved for the thousandth time, that this order, continually urged by infernal ambition, meditates the ruin of all liberty, and by its counsels is hurrying princes, nobles, and states to their ruin. It is its suggestions that petrify the heart of the King of Naples, in whose dominions one of the members of the Company has been heard preaching the most hideous absolutism and blind obedience, as the most sacred and inviolable duty of the multitude. This is their very doctrine; and when they preach a different one, it is but a trick, and is practised there only where they lack the support of despotism.

Lastly, let us hear the captive of St. Helena expressing his whole opinion of this order. But be it remembered in the first place, that it is not for the sake of right and reason Napoleon declares himself an enemy to Jesuitism. He feared reason; right he deemed a thing not to be realised; and as for liberty, he could never comprehend it. “Louis XIV.,” he exclaimed,. “the greatest sovereign France has had! He and I— that is all.”*

* Recits de la captivite de l’Empereur Napoleon a Sainte Helene, par M. le General Montholon. Paris, 1847, t. 2, p. 107.

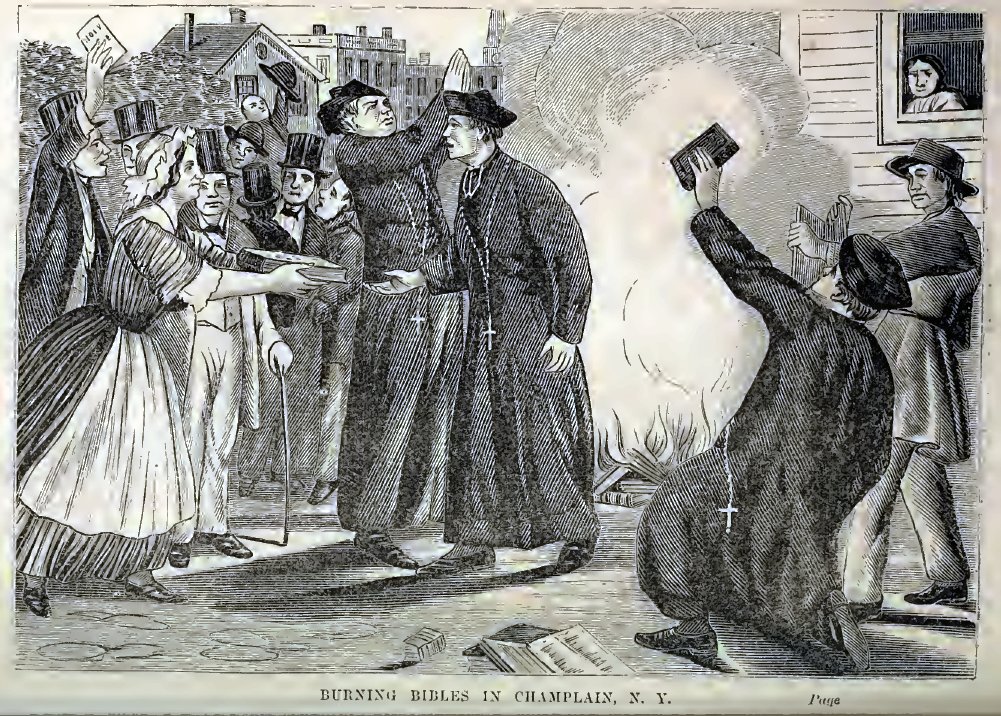

He even thought that the people should not be allowed the Bible. “In China,” said he, “the people worship their sovereign as a god, and so it should be.” Now, he felt strong enough, as he says, to make the pope his tool, and Catholicism a means of his power. He liked the latter, because it enjoins men to distrust their reason and believe blindly. “The Catholic religion is the best of all, because it speaks to the eyes of the multitude, and aids the constituted authority.” In another place he says he prefers it because “it is an all-potent auxiliary of royalty.” He admitted all sorts of monks, and thought he could make something of them, except the Jesuits. On his rock he speaks of them with nothing but abhorrence, and is convinced that he could not resist them with more profound or more decisive means than their own; and that wherever they exist, such is the force of their stratagems and manoeuvres, that they rule and master everything in a manner unknown to everybody.

“But,” says he, “a very dangerous society, and one which would never have been admitted on the soil of the Empire, is that of the Jesuits. Its doctrines are subversive of all monarchical principles. The general of the Jesuits insists on being sovereign master, sovereign over the sovereign. Wherever the Jesuits are admitted, they will be masters, cost what it may. Their society is by nature dictatorial, and therefore it is the irreconcilable enemy of all constituted authority. Every act, every crime, however atrocious, is a meritorious work, if it is committed for the interest of the Society of Jesus, or by order of the general of the Jesuits.”*

* Becits de la captivity &c., t 2, p. 294.

VI.

The first step in the reform of Catholicism is the absolute abolition of this order: so long as it subsists it will exert its anti-social and anti-christian influence over the Church and the Powers; and so long as the Church is filled with the hatred for progress which that order cherishes, it will only hasten its own decay, and its regeneration will be impossible.

Part I. Novitiate and Ecclesiastic Career.

I.

At the age of nineteen I had formed the resolution of entering the church, and was finishing my studies at the Seminary of Vercelli. I usually passed my vacations in the company of Luigi Quarelli, arch-priest and cure of Langosco, my native place. Incited by an eager thirst for knowledge, I had, in the course of a few years, completely exhausted his library; and often did this worthy man repeat to me, that so far from learning being of any use to me, it would more probably be an obstacle to my advancement in the church. He now began to speak to me of the Jesuits. The power of this order, its reverses, its recent restoration, the impenetrable mystery in which it has been enveloped since its origin, all contributed to exalt it in his eyes. According to his account, none were admitted into it but such as were distinguished for intellect, wealth, or station. He spoke of it as the only order which, so far from repressing the native energies of the mind, or the tendencies of genius, did actually favour them in every way. This assertion he substantiated by many striking examples.

The impression made on me by these conversations was exceedingly strong. Young, inexperienced, and dazzled by statements which taught me to regard Jesuitism as the only resource of a noble ambition, I longed for nothing so much as to be received into the order. Neither the thought of abandoning my parents, nor that of the severe trials to which I must subject myself, could, in any way, divert me from my purpose.

The cure scrupulously examined my resolution, and the result being satisfactory, he wrote to Turin, to Father Roothaan, then rector of a college of the society in that town, and now general of the Jesuits. The rector, after having made the customary inquiries respecting me, intimated that I might repair to the capital, and undergo the preliminary examinations.

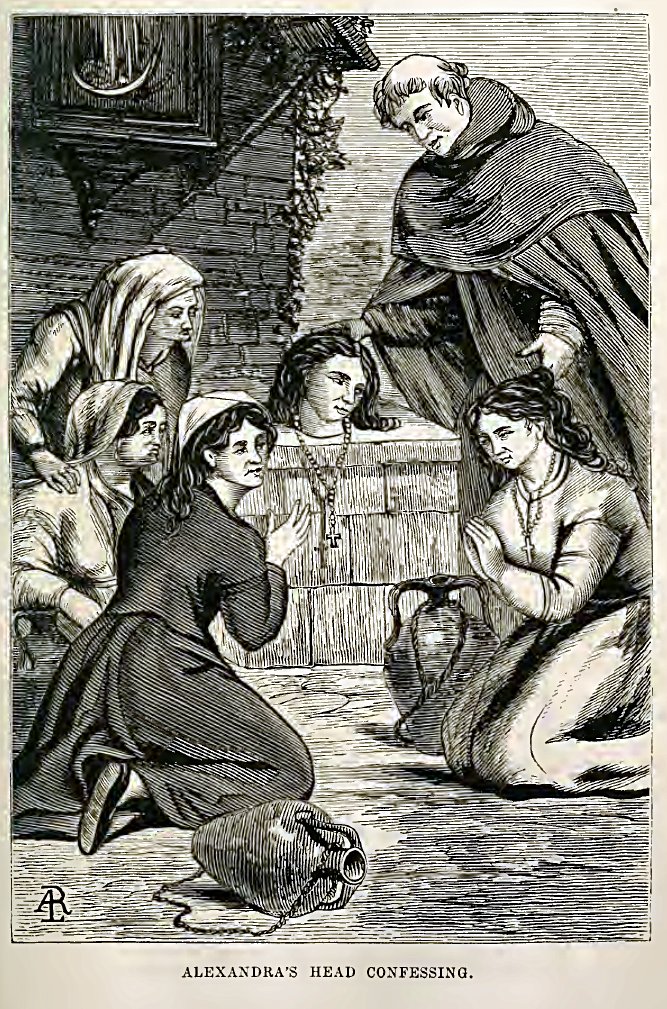

I therefore took my departure. When I presented myself to him, he conversed with me for some time, and with great openness and affability. At first, his object appeared to be merely to acquaint himself with the extent of my acquirements, but by degrees he led me on insensibly to make a general confession, as it were, of my whole life.

I will not here attempt to retrace the details of this conversation. It would be difficult for me to convey an idea of the consummate art employed to sound a conscience, to descend into the very depths of the inmost heart, and to make all its chords resound, the individual remaining, all the while, unconscious of the analysis which is going on, so occupied is he by the pleasant flow of the conversation, so beguiled by the air of frank good-nature with which the artful process is conducted.

I have retained but vague and disjointed recollections of all these subtle artifices. One portion of the conversation, however, imprinted itself so deeply in my memory that I will repeat it, in order to show under what point of view the present chief of the Jesuits had already begun to regard the mission and aim of his order.

“And now,” said he, after having examined me, “what I have to communicate to you is calculated to fill you with hope and joy. You enter our society at a time when its adherents are far from numerous, and when there is, consequently, every encouragement to aspire to a rapid elevation. But think not that on entering it you are to fold your arms and dream. You are aware that our society, at one time, flourished vigorously, that it marched with giant steps in the conquest of souls, and that the cause of Christ and of the Holy See achieved signal victories by our means. But the very greatness of the work we were fulfilling, excited envy without bounds. The spirit of our order was attacked, all our views were misrepresented and calumniated, and as the world is always more ready to believe evil than good, we came, ere long, to be universally detested.

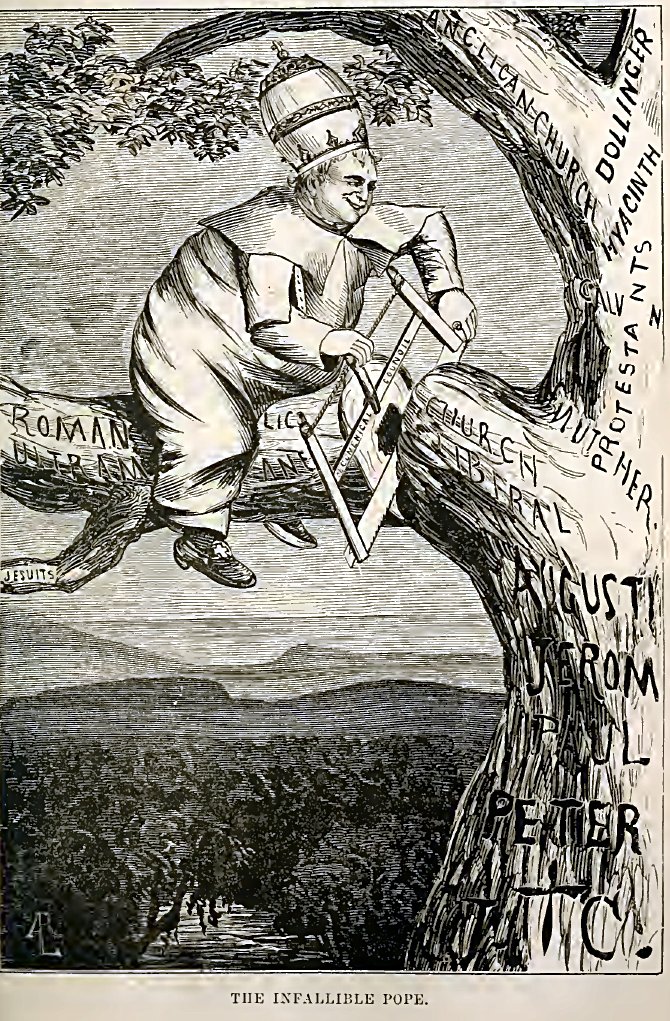

“Thus, we, the Society of Jesus, were doomed to undergo the same trials as our Divine Master. We were loaded with insults, we were driven from every resting-place. Monarchs and nations entertained with respect to us but one common thought, that of sweeping us from the face of the earth. Humiliated, insulted, buffeted, crowned with thorns, and bearing the cross, we also were doomed to suffer the death of ignominy. There was not wanting even a Caiaphas (allusion to Pope Clement XIV. who banned the Jesuits) to sign our sentence with his own hand; and the chastisement with which he was soon after visited by the just judgment of Heaven (the Jesuits murdered him with poison), gave rise to a last calumny against us, which crowned all the others. Our last struggle was ended; we died—but though dead, the powerful still trembled at our name. They made haste to seal up our tomb, and they set over it a vigilant guard, so that there might not be the faintest sign of life beneath the stone which covered us.

“But behold what became of the potentates themselves, during our sleep of death! (Meaning during the suppression of the Jesuits.) Day by day they were visited by chastisements more and more severe. The world became the theatre of direful troubles and terrible catastrophes. A giant threaded (infilzava) (Italian meaning speared) crowns upon his resistless sword, and monarchs were cast down in the dust at his feet. But the moment of terror soon arrived, in which Almighty God broke the sword of the man of fate, and called us from the sepulchre. Our resurrection struck the nations with astonishment; and now we shall be no more the sport and the prey of the wicked, for our society is destined to become the right arm of the Eternal!

“Thus, a new era is opening for us. All that the church has lost she will regain through us. Our order, by its activity, its efforts, and its devotedness, will vivify all the other orders, now well nigh extinct. It will bear to all parts the torch of truth, for the dispersion of falsehood; it will bring back to the faith those whom incredulity has led astray; it will, in a word, realise the promise contained in the gospel, that all men shall be one fold under one Shepherd.

“Henceforward, then, no more disasters; the future is wholly ours. Our march will be victorious, our conquests incessant, our triumph decisive.