The Antichrist: His Portrait and History – Chapter VII. Antichrist Revealed by Chain of Evidences

Continued from Chapter VI. Identification of Antichrist.

It will be observed from the foregoing, that out of their own mouths Popes, Cardinals, Bishops, Priests and Jesuits have convicted the Pope of Rome of being “The Antichrist” of Holy Writ, and Ho Antichristos of prophecy, the “little Horn” of Daniel, and “Willful King” of the Romans, who “doeth according to his own will,” who is seated in a false “Apostolic See,” whose “mouth speaketh great things and blasphemies,” whose official title is “Roman Pontiff,” or Pontifex Maximus, i.e., heathen, who, by deeds and words, by assumptions and claims, poses as God within Christ’s Church, and who “exalts himself above all that (on earth) is called God,” whether they be monarchs or princes, magistrates or bishops.

But these are not the only points of identity between the Scripture portrait and the reality. We have other striking evidences:—

(a) SEAT OR THRONE OF ANTICHRIST.

For instance, take the “seat” of the False “Apostolic See,” which is thrice mentioned in prophecy, viz., Daniel xi. 38; 2 Thess. ii. 4; and Rev. xiii. 2. There it is referred to as a “seat” (the see of a “seer,” as Daniel vii. 8 describes it), in which the “God of Forces” —i.e. Hercules—is honored; as a “Cathedra” usurped in the mystical “Shrine of God” or professing Church; and as a “throne” of earthly power derived from the inspirer of Paganism. As already shown, it was described by the Romish Bishop of Waterford as a “Papal Throne,” on which sits “one who exercises the authority of the Great God Almighty Himself.”

This “throne” is thus described in “Christmas Holidays, etc.” (p. 47): “The magnificent throne of the Pope, raised quite as high as the altar, which it fronted, and decked out most splendidly with its cloth of crimson and gold, and the gilded mitre suspended above.” . . . “His throne was far more gorgeous than the altar; where they kneeled down before the latter once, they kneeled down before the former five times; and the amount of incense offered before each was about in the same proportion. Had I known nothing of Christianity, I should have supposed the Pope to be the object of their worship. He was evidently the central point of attraction.”

This “throne” is only used on the occasion of the Pope celebrating Mass on certain “Festivals.” Other “thrones” are used by him on other occasions; as, for instance, the “Sedia Gestatoria,” or portable seat, in which he is borne aloft above the heads of all present—”above all that is called God”—whether kings, princes, magistrates, bishops or priests. Here is what “The Universe ” (June 27th, 1846) and the official document, “Notitia Congre, et Tribunal Curie Romane, Littenburg, 1683,” both said about the Coronation of a Pope: “After the Election and Proclamation, the Pope, attired in the Pontifical habit, is borne in the Pontifical Chair to the Church of St. Peter, and is placed on the High Altar, where he is saluted (Picart uses the word ‘adored’) for the third time by the Cardinals, by kissing his feet, hands, and mouth.” In this portable throne or seat the Pope is carried backwards and forwards between his palace of the Vatican and St. Peter’s.

Picart, the Romish historian of Papal Ceremonies, gives a full account of the Election and Coronation of a Pope, as described in the official Roman “Ceremonial.” It involves five “Adorations” of the Pope. In the second he is seated “upon the altar of Sextus’s chapel”; in the third upon “the great altar”; in the fourth on a “throne” under a canopy in the portico of St. Peter’s, and thence carried to a “throne” in the Gregorian Chapel, where, seated, he receives the “homage” of Cardinals, ambassadors, princes, prelates, etc., the Cardinals kissing his hands, the rest his knees. This is the Fourth “Adoration.”

On the arches raised in honor of Pope Borgia were the words “Rome was great under Caesar; now she is greater: Alexander VI. reigns. The former was a man: this is a god.” Lord Acton (“Letters on Modern History,” p. 79) said: “The scandals in the family of Borgia did not prevent Bishops calling him a god.” Julius II., in the 4th Session of the 5th Lateran Council, A.D. 1512, was thus addressed: “For thou art the shepherd, thou art the physician; thou art the governor; finally, thou art another God on earth,” E. C. Gardiner’s “St. Catherine of Siena” describes Urban VI. as “Christ upon earth.”

Picart unconsciously describes the fulfillment of 2 Thess. ii. 4, for he adds: “The Holy Father is undressed, in order to put on other robes, the color whereof is a type or symbol of his purity or innocence. The Cardinal-deacon clothes His Holiness in a white garment, who, in the language of Scripture, is to preside in the temple of the Lord.”

After this the Pope is carried to the “High Altar,” and descends, and ascends his own “throne” —upon which he receives the fifth Adoration.

After this he is carried to the “Benediction-Pew” in his sedia gestatoria, under a canopy, supported by Roman conservators and caparions, two grooms in scarlet, carrying fans of peacocks’ feathers, on either side of the chair. The pope ascends a “throne” in the pew, and is invested with the Papal Triple Crown, with the words, “Receive this tiara embellished with three crowns, and never forget, when you have it on, that you are the Father of Princes and Kings, and the Supreme Judge of the Universe (or ‘Ruler of the World,’ as another authority says); and, on earth, the Vicar of Jesus Christ, our Saviour.” Whereupon, the Pope “blesses” the people thrice; a “Plenary Indulgence” is proclaimed; cannons roar out a triple peal; bonfires blaze; rockets are fired; houses are illuminated; horse and foot soldiers present arms.

Some days later the Pope proceeded in state (this was before 1870) to St. John de Lateran—the Cathedral of the Bishop of Rome—under triumphal arches, and with most gorgeous pageantry of scarlet, gold, silver, silks, purple velvets, satins laced with gold, precious stones, and almost everything enumerated in Revelation xviii. 12, 13—filling a whole folio in small print—there to be again “enthroned” and “adored,” with honors no emperor or king has ever received.

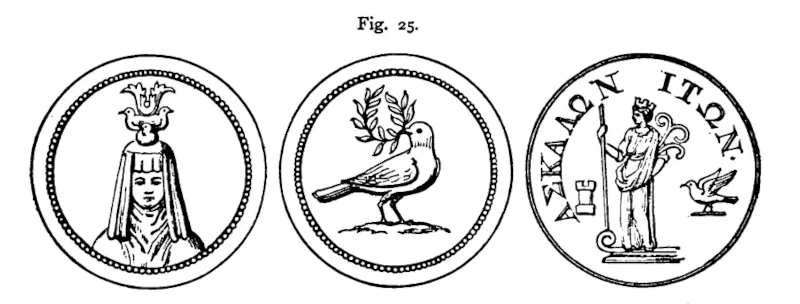

But there is yet another “seat” or “throne” for the Pope. It is in St. Peter’s, at the extreme end of the building, and commands the entire interior. It is over an “altar,” with a colossal reredos (a screen, or decoration placed behind the altar in a church) of bronze, in the center of which is the throne—within which, hidden from view, is the so-called “Chair of St. Peter.” This “throne” is supported by images pretending to be Augustine and Ambrose—Latin ** Fathers,’’ Chrysostom and Athanasius—Greek “Fathers.” Above it is a Dove, surrounded by angels, boys and nymphs, in the midst of rays of light. Angels are gazing down at the Pope’s bronze throne, with the seat inside. Directly under the bronze case is the “altar.” Thus the place of Romish “authority” and “teaching” is above the Sacrifice of the Mass or the Immolated Victim on the altar, i.e., is “above God.”

Directly over the chair, exactly where the occupant’s head rests, is a crown upheld by angelic hands. Above these angels is the emblem of God the Holy Spirit, from which rays of light pour down upon this “throne” or “seat.” It is from this chair that the Head of the Latins, or Lateinos, claims the Headship of the Universal Church of Christ, and from it claims to be “Vicar of Christ,” i.e., in Greek, Antichristos. It is the False Apostolic Chair, whence are derived the “Petrine claims” of the Latin Papas. Below it is an “altar,” on which this Latin man first makes his God, and then sits in order to be “adored” by those whom the Council of Trent “called gods,” i.e., bishops and priests.

(b) ROMISH TESTIMONY TO IDENTITY.

Cardinal Wiseman (“Recollections of the Pope,” pp. 229, 230) said: “The Papal throne is lofty, and is erected opposite the altar, in the sanctuary.

“The Altar is the object of all reverence, (2 Thess. ii. 3, 4) towards it, all kneel and worship the consecrated elements there.” (A terrible admission of idolatry.)

Archbishop Ullathorne said (“Letters from Rome,” p. 216): “The multitudes kneel when the Pontiff lifts up the God of Heaven and earth in his mortal hands.”

Cardinal Manning (“Sermon on the Pope’s Jubilee”) declared that “The priest’s hand is the instrument of bringing the Lord of Heaven on the Altar.”

Said Mr. Eustace, a Popish priest, who witnessed this “Adoration” of the Pope: “I object not to the word ‘adoration’ . . . but why should the altar be made his footstool? The altar—the beauty of holiness, the throne of the Victim-Lamb, the mercy-seat of the temple of Christianity; why should the altar be converted into the footstool of a mortal?” (“Classical Tour,” Vol, IV., Appendix, p. 396, Leghorn Edition).

Well might Mr. Gladstone, in his “Rome: Newest Fashions in Religion” (p. 172), ask the Pope to explain the meaning of a photograph sold in Rome by Cleofe Ferrari, representing “a double scene, one in the heavens above, one on the earth below.” “Above . . . is one of those figures of the Eternal Father which we in England view with repugnance. On the right hand of that figure stands . . . the Blessed Virgin Mary, with the moon under her feet (Rev. xii. 1); on the left hand . . . is St. Peter, kneeling on one knee—kneeling to the Virgin, not to God. In the scene below . . . on the pedestal is Pope Pius IX., in a sitting posture, with his hands clasped, his crown, the Tri-regno, on his head, and a stream of light falling upon him from a dove, forming part of the upper combination, and representing the Holy Spirit. The Pope’s head is not turned towards the figure of the Almighty. Round the. pedestal are four kneeling figures apparently representing the four great quarters of the globe, whose corporal adoration is visibly directed towards the Pontiff. . . We commend this most profane piece of adulation to the notice of the Cardinal Vicar.”

That the Antichrist of prophecy is the Latin Papacy is proved by the Roman Missal, the Decrees, Canons, and Catechism of the Council of Trent—when compared with I Tim iii.: 2:Thess. ii.: Rev. xiii., xvii., as well as the following Early Testimonies of the “Fathers”:

Irenaeus: “The number of Antichrist’s name shall be expressed by this word, LATINUS”;

Sybilla: “The greatest terror and fury of his Empire, and the greatest woe that he shall work, shall be by the banks of Tiber”;

Jerome: “Antichrist shall sit in the temple of God, either at Jerusalem, as some think, or else in the Church itself, as we more correctly consider”; “Antichrist shall cause all religion to be subject to his power”;

Gregory I.- “I speak it boldly, whosoever calleth himself Catholic Priest, or desireth so to be called, in the pride of his heart, is the forerunner of Antichrist”; “By this pride of his (John, bishop of Constantinople), what thing else is signified, but that the time of Antichrist is even at hand”; “The King of Pride is coming to us, and an army of priests is prepared …”;

Bernard: “The Beast that is spoken of in the Book of Revelation … is now gotten into Peter’s chair,” and though these words were spoken against Petrus Luna, who usurped the see of Rome in the time of Pope Innocent VII., they prove that in (Romish “Saint”) Bernard’s judgment the Antichrist can sit in Peter’s chair: “Bestia nolens os Ioquens blasphemias occupat Cathedram Petri”; (From Google translation of the Latin: Beasts unwillingly speaking blasphemies occupy the Chair of Peter.)

Joachim Abbas: “Antichrist is already born in Rome, and shall advance himself higher in the Apostolic See”;

Arnulphius, in the Council of Rheims: “What think you, reverend Fathers, of this man sitting on high in his throne, glittering in purple, and cloth of gold? Verily if be be void of charity . . . then he is Antichrist sitting in the temple of God, and showing out himself as if he were God”;

The Bishops in the Council of Reinspurg: “Pope Hildebrand under a color of holiness hath laid the foundation for Antichrist”;

Dante calls Rome the “Whore of Babylon”;

Petrarch: “Rome is the Whore of Babylon, the Mother of Idolatry and Fornication, the Sanctuary of Heresy, and the School of Error.”

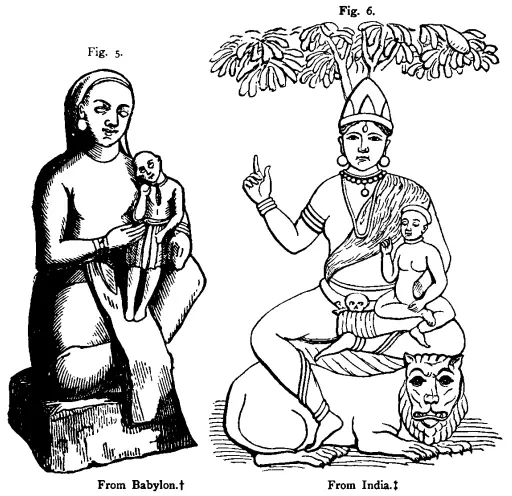

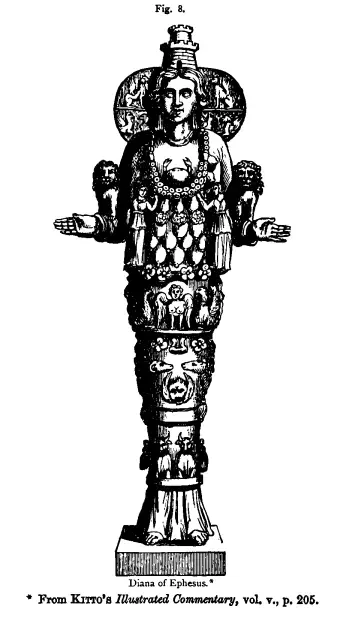

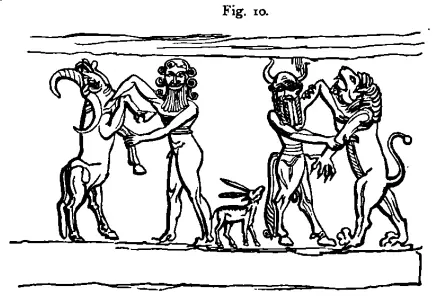

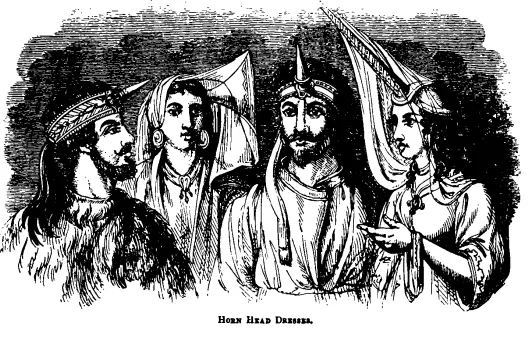

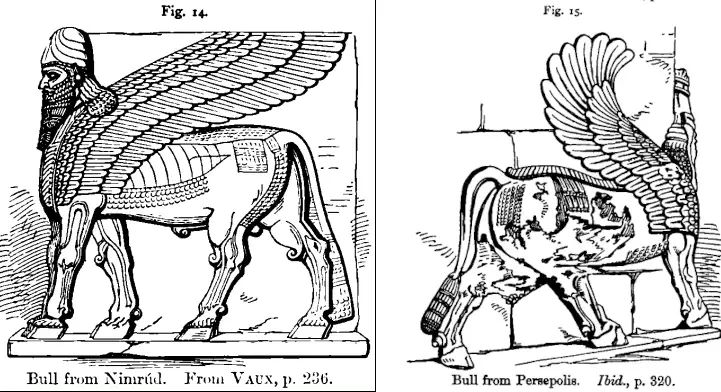

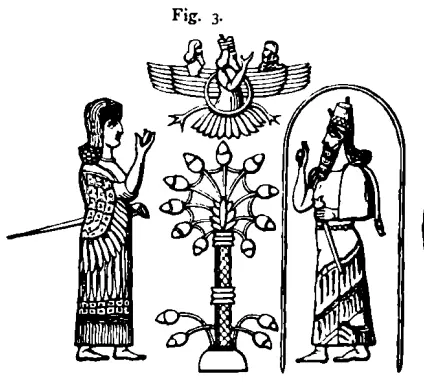

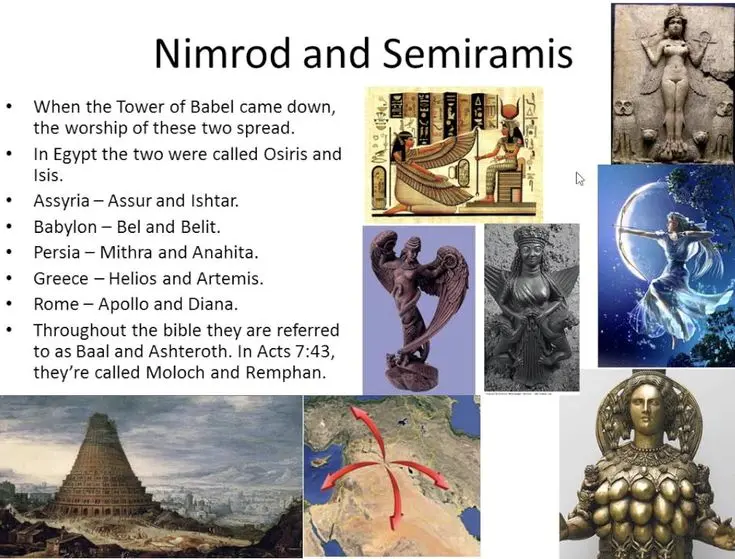

(c) HEATHENISM DISGUISED.

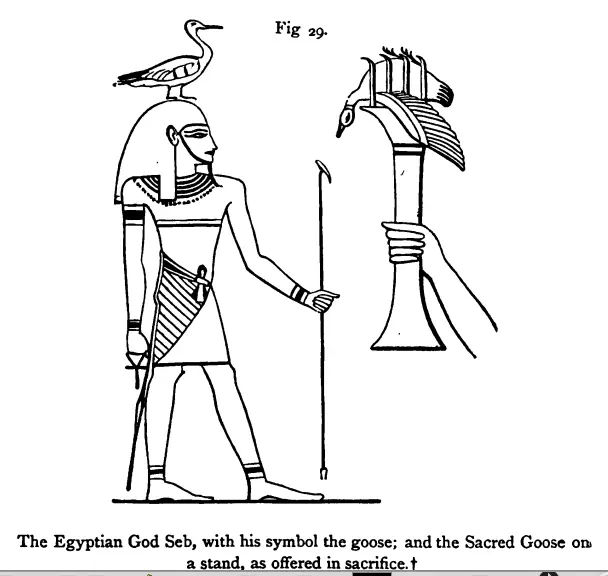

The “Chair of St. Peter” is heathenish. The “altar” below it is heathenish. The “Adoration” of the Pope is heathenish. The “kneeling” to the image of the Virgin ts heathenish. The peacocks’ feathers, or Filabelli, are heathenish (Egyptian). The processions and pageantry are heathenish. Everything about the Latin man and his religion is heathenish—Romish Cardinals and Archbishops being witnesses. Thus the “Archbishop of Birmingham,” in his Mid-Lent Pastoral, in 1917, said: “During Passiontide the Church, by her public offices and liturgy, and by the draping of altars and statues, intimates . . . the Sacred Passion. Yet on Maundy Thursday she puts off her garments of sorrow and resumes her festal attire . . . that we may . . . rejoice in the institution of the adorable sacrifice” of the Mass! This is imitated from the old Pagan worship, in which the clothing of the gods occupied an important place (see Homer’s Iliad, vi. 269-311).

The bronze statue of St. Peter at Rome was formerly a statue of Jupiter—as Torrigio (8th century) admits (II Vaticano Illustrato, and Brock’s Rome: Pagan and Papal, p. 121). On various annual solemnities, it is the custom to clothe this image in full Pontifical dress, “and so to present it for the worship of the faithful, rich with gold and gems” (Ibid. pp, 123.and 431)… Picart (Vol. I., p. 13) thus refers to the modern Romish custom of kissing images: “With us the priest kisses the altar, the cross, the relics, the thurible, the paten and the chalice.” The bronze image of St. Peter is brightly polished by the kissings and rubbings of worshipers, including the Pope. Cardinal Baronius (d. 1607) was the first to introduce its worship . . . which laudable custom others followed, to the wearing away of the brass of the statue” (Ciacconius: 4 vols. fol. Rome: 1677). 600 years B.C., apostate Israelites kissed the calves (Hosea xiii. 2), and a century earlier, they adored Baal and kissed the bloodstained idol of Phoenicia (2 Kings xix. 18), just as the heathen used to kiss the image of Hercules at Agrigentium.

Rome boasts that it has “Christianized” Paganism by adopting its worship, and changing the names of the images! In reality it has paganized Christianity!

The following extract from the Christian World supplies the answer:—”Newman, in a passage of his ‘Essay on Development,’ speaking of the early Catholicism in its contact with the heathen world, says:— ‘Temples, incense, lamps, and candles, votive offerings, holy water, asylums, holy days, and seasons, processions, blessings on the fields, sacerdotal vestments, the tonsure, the ring in marriage, turning to the east, images, and the Kyrie Eleison are ALL OF PAGAN ORIGIN, and sanctified by their adoption into the Church.’ Pope Gregory the Great, in his letter to the English missionaries, gives the rationale of the process. ‘Let them,’ he says, ‘hang garlands round their temples, turned into churches, and let them celebrate such festivals with modest repasts. Instead of immolating animals to demons, let them kill such animals and eat them . . . so that, by allowing them such material pleasures, they may the more easily be brought to share in spiritual joys. For it is impossible to expect savage minds to give up all their customs at once.’”

The passage from Cardinal Newman will be found in his Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, London, 1846, p. 359.

(d) FULFILLMENTS OF PROPHETIC FEATURES.

This leads us to the fulfillment of Revelation xiii. 11-17 and xix. 20, or the identification of the “False Prophet” or Pagan False Priesthood, for that that is the meaning of “two horns like a lamb” is clear from the facts: (1) that our Lord used a parallel simile to denote false Christian ministers (Matthew vii. 15); and (2) the word “Lamb” is everywhere in the Apocalypse the symbol of Christ, and therefore the figure necessarily denotes a False Christian ministry; which, being a “Wild Beast,” is of heathen origin.

Now the “Canon Law” of Rome is a compilation of documents, some of them emanating from Popes, but the majority from Papal Councils and so-called “theologians” and Romish priests. It is principally in this enormous “Corpus Juris Canonici” that are found all the false claims of the Popes, their false teaching, their false history, their usurpations. It is in the “Canon Law” that the Pope is called God, (Decretum Gregorii, XII.) and “Lord God.” (Decretals, Gregory IX.) It is in the “Canon Law” that the Pope is described as “God, because he is God’s Vicar.” (Decretals of Innocent.) In fact, Romish writers style the “Canon Law” and “Decretals” the “Pope’s Oracle,” as representing the Pope’s mind. Romish casuists say of the Pope: “As Christ was God, he, too, was to be looked on as God.” The “Sacrum Ceremoniale” speaks of “The Apostolic Chair” as “The Seat of God.” By permission of priestly superiors, works are published by Romish ecclesiastics, styling the Pope “Vice-God.”

Papal excommunications and anathemas are styled “Fire from Heaven” by Papists. Thus Gregory VII. spoke of Henry IV. as “struck with thunder“—afflatum fulmino; and at the first Council of Lyons, the excommunication of the Emperor Frederick by Pope Innocent is described thus: “These words, uttered in the midst of the Council, struck the hearers with terror, as might the flashing thunderbolts, when, with candles lighted and flung down, the Lord Pope and his assistant prelates flashed their lightning fire against the Emperor.

In the Roman “Pontifical,” compiled by ecclesiastics, the following is put into the mouths of Popish Bishops when threatening the “greater excommunication” (or, as it is called in Ireland, “Putting fire to your heels and toes”): “We adjudge you to be anathematized and condemned with the devil and his angels, and all the reprobate in eternal fire . . “; “We separate (Rev. xiii. 15, 17) you from the fellowship of all Christians and exclude you from the threshold of the Holy Mother Church in Heaven and earth, and decree you to be excommunicated.”

By a General Papal Council of Ecclesiastics was the Bull “Unam Sanctam” enacted, which subjected everyone to the Pope. Gregory, Bishop of Rome, himself realized the force of the prophecy when he declared, “The King of Pride is at hand; and an army of priests is prepared,” “because the clergy war and strive for mastery and advancement, who were appointed to go before others in humility”; “under the aspect of sheep we nourish the fangs of the wolf.” History tells us that from the time of Gregory, the ecclesiastics of Rome were one body, under one papal head, bishops lording it over secular priests, abbots and generals of monastic orders over the “Regulars”;—”Seculars” and “Regulars” forming the “two horns” of the pretended Lamb-like pagan hierarchy, all alike employed in deceiving the laity, and enforcing the claims of the Pope, “before him” (Compare 2 Tim. iv. 1, 2) i.e., with his sanction, approval and support.

It must never be forgotten that as “Bishop of the Apostolic See,” the Pope claims the headship of the Universal Church, and lordship over all ecclesiastics—Regular and Secular; whilst, in his capacity as successor of the Caesars, and occupier of their “throne,” he claims the lordship over all temporal powers in the Roman earth. Beyond and above these two claims, he, as “Vicar of Christ,” or “Vice-God,” poses as “King of Kings, and Lord of Lords,” with power over Heaven, and Earth, and Purgatory—a claim embodied in the Triple Crown he wears.

The Tiara

St. Peter’s and the Vatican.

Hence the Bull “Unam Sanctam” declares it essential to salvation to be subject to the Pope. Accordant with which claim, all ecclesiastics take the vow of “obedience,” and receive the Sign of the Cross (“Pontificale Romanum,” p. 49) as a sign of obedience to the Pope; and these, in turn, administer to emperors and kings, and to all within the confines of the Latin Church, the oath of submission to the Pope, and fealty—along with the “Sign of the Cross,” which is impressed upon the foreheads, or hands, with the right hand of the operator—even as a great army of soldiers under the papal banner—from birth right onwards to death.

When the Crusaders captured Jerusalem, they established “the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem,” they all being Papists. And when the Easterns separated from the Westerns, they denominated the latter, because of their subjection to Rome, “the Latins,” a name which has ever since the sixth century described the religion emanating from Rome, as well as the nations connected with that city. “Latin” has been the peculiar distinctive title of the Popedom, of its religion, of its hierarchy, and of its “Image” or Representative Oracle – Papal Councils. Historians, with one accord, describe “the Latin world,” “the Latin Kingdoms,” “the Latin Church,” etc. The only Bible ever adopted by Rome is the Latin Vulgate. Papal Bulls, Papal Councils, the Mass, all speak in Latin. Hence Irenaeus’s elucidation of the “Name of the Beast” as the name of the man. Lateinos, was marvel- lously “wise.”

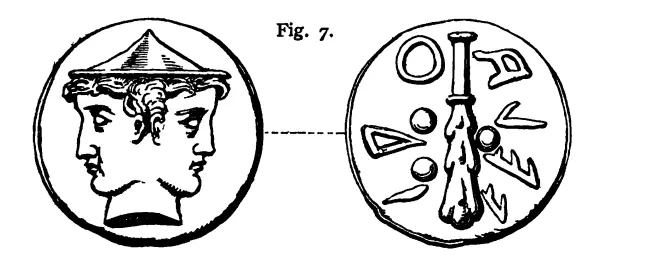

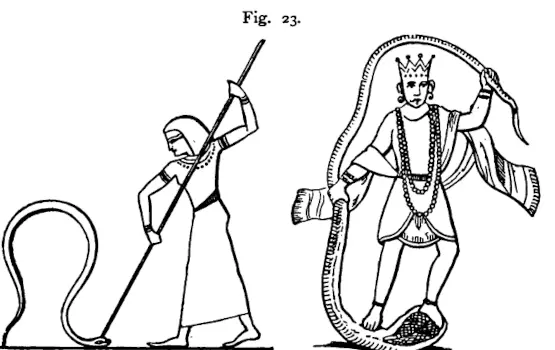

(e) THE NAME OF A MAN.

Now, who was Lateinos (or Latinus, in Latin)? He was the head and originator of the Latin race—a prince, supposed to be the son of Faunus and the nymph Marcia. He ruled the country bordering on the Tiber. His daughter, Lavinia, married AEneas, the Trojan, and from them were descended the founders of Rome, viz., the people of Latium, or Latins. Julius Caesar claimed lineal descent from AEneas and Latinus—the first Latin man. “The” Beast bears his name. The “name of the Beast,” therefore, is Latin. “The Beast” itself must be a “Head” within the confines of the fourth Wild Beast of Prophecy—or Latin Power of Rome— as all admit. It must be arrogant and self-exalting; its voice must be imperious and loud; in its “seat” or “throne” must it honor Hercules, the pagan god; its coadjutor and myrmidon must professedly be a Christian “prophet” or priestly class—with “two Lamb-like horns”—claiming miraculous powers, displaying intolerance, and insisting on a pagan symbol as a mark of faith, on pain of excommunication, or as expressed in Revelation xiii, 15-17, “that no man might buy or sell, save he that had the mark or name of the Beast, or the number of his name”—which, translated from symbol to fact, means boycotting, or exclusive dealing against all who were not signed with the mark of the Beast, i.e., the Cross, or were not Latins, i.e., Papists.

(f) REVELATION XIII. 17.

All this, and much besides, has been realized by the Papal Ecclesiastics—Regular and Secular—for the past twelve hundred years. A canon of the Lateran Council, under Pope Alexander III., decreed that no one should entertain or cherish heretics in his house or land, or exercise traffic with them.

The Synod of Tours forbade Papists from buying from, or selling to, “heretics”; so, too, the Council of Constance. In short, no “heretic” may be traded with, or associated with, by any “good Catholic,” according to Canon Law and Romish teaching. Hence the “boycotting” in Ireland, and the priestly condemnation of “Protestants,” the “No- Rent” manifesto, and all the bigotry and intolerance displayed by Jesuits, monks, nuns, and priests of Rome, who claim superhuman power—even that of changing bread into God, of compelling Christ to descend every day from Heaven, to consign to Hell-fire, to immolate Christ, to “put fire to heels and toes,” to forbid commercial transactions and to command persecution. “The History of Freedom and Other Essays,” by John E. E. Dalburg Acton. Edited by J. N. Figgis, Lit.D., and R. V. Lawrence, M.A., pp. 138- 141. (Macmillan, 1909.) “It is part of the punishment of heretics that faith shall not be kept with them. It is even a mercy to kill them, that they may sin no more.”

(g) THE LAWLESS ONE (HO ANOMOS). 2 THESS. II. 8.

Nor is there any difficulty in identifying HO ANOMOS, the Lawless One, or person exempt from law. For, not only by Papal Bulls, Edicts, Encyclicals, and Decrees have commands been issued deliberately contrary to God’s Laws, Christ’s injunctions, and to Scripture—such as clerical celibacy, monastic fasting and false piety, persecution of heretics, crusades, marriage within prohibited degrees. (for instance, the Duke of Aosta was allowed by Pope Leo XIII., for the sum of £4,000, to contract an incestuous marriage with his own sister’s daughter, Princess Letitia), indulgences, canonization of the dead, deposing power, temporal power, and so on; but also claims have been, and are, put forth absolutely opposed to Truth, to fact, and to earthly laws made by nations and rulers for the betterment of their states; claims to be above all law. “Papa solutus est omni lege humana. The Pope is exempt from all human law.”

Cardinal Manning, speaking for the Pope, said: “I am liberated from all civil subjection . . . I acknowledge no civil superior. I am the subject of no prince . . . The subject of no one on earth . . .”

In the Decretals of Pope Gregory IX. we read that the Pope “is said to have a heavenly power; and hence he changes even the nature of things, applying the substantials of one thing to another, and can make something out of nothing; and a judgment which is null he makes to be real; since in the things which he wills his will is taken for reason; nor is there anyone to say to him: ‘Why dost thou this?’ for he can dispense with the Law; he can also turn injustice into justice by correcting and changing the Law, and he has the fullness of power.”

By the Vatican Decree of July, 1870, it was declared that “such definitions of the Roman Pontiff . . . are irreformable.”

Indeed, the very words of Daniel vii, 25 were embodied by the Pope in one blasphemous Decree: “Wherefore, no marvel if it be in my power to change times and laws, to alter and abrogate laws, to dispense with all things, yea, with the precepts of Christ.” This was Pope Nicholas.

The Romish “Canonist,” Reiffensteul, as well as other authorities and Popes, deliberately have taught that the Pope has power to “absolve” from oaths, to “dispense from” oaths, to “annul” oaths, and, generally, to play fast and loose with oaths. In the “Decretum,” Part II., Canon XV., Quaest. VII., we read that the Pope’s authority “altogether annuls unlawful oaths,” “absolves from oath of allegiance”; and that “those subject to an oath of allegiance to an excommunicated person, are not bound.” In the “Decretals of Gregory,” Book II., tit. xxiv., ch. xxvii., says: “An oath taken against the Church’s interest does not bind.”

That this teaching is acted upon we have evidence. Thus Pope Pius IX., in his “Encyclical” of February 5th, 1875, declared certain Prussian Laws “null and void,” and excommunicated the framers of them (“Tablet,” February 27th, 1875).

In 1855 he declared to be absolutely null and void the Laws of the Piedmontese Government; and of the Kingdoms of Sardinia and of Spain; in 1856 those of Mexico; in 1862 those of Austria; in 1863 those of New Granada; on the ground of the inherent right of the Pope to disannul all Laws relating to the Roman religion (see “Constitutio Apostolicae Sedis” also, which was in 1869 substituted for the Bull, In Caena Domini).

Lord Acton tells us that Pope Gregory XIII.’s reply to the French King’s announcement of the Massacre of St. Bartholomew was “that he desired for the glory of God, and the good of France, that the Huguenots should be extirpated utterly” (“North British Review,” October, 1869).

Pius V. declared that he would release a culprit guilty of a hundred murders rather than one obstinate heretic. He wished to destroy Faenza because of its “heresy.” He adjured the French King to make no terms with Huguenots, and not to observe the terms he had made. He ordered them to be pursued to death. The same ideas pervaded the “sacred College” under Pope Gregory (Ibid.).

Lord Acton (“Essays on Liberty,” pp. 140, 141) said that the many plots and massacres that brought disgrace upon the Church of Rome were based on the theory that: “Treaties made with heretics, and promises given to them, must not be kept, because sinful promises do not bind, and no agreement is lawful which may injure religion or ecclesiastical authority.

“No civil power may enter into engagements which impede the free scope of the Church’s law. It is part of the punishment of heretics that faith must not be kept with them. It is even mercy to kill them that they may sin no more.”

The Jesuit organ, “The Month” (Vol. XVIII. for 1879, p. 320), said: “It is false to say that the Pope can, in no instance . . . absolve from an oath.”

As further examples of Papal lawlessness, let the following be considered. Pope Innocent III. said: “We can dispense from law, according to our plenitude of power over law” (“Decret. Greg. IX.,” 8, iv.). Pius IX., writing to Count Duval de Beaulieu (“Allegemeine Zeitung,” November 13th, 1864), said that “the Church” has power over the Government of Civil Society, and direct jurisdiction and right of interference in temporal matters. (It is on this evil principle that the Popish Bishops in Ireland have lately urged opposition to Conscription—a matter wholly outside “the Church”), The Jesuit organ in Rome, “Civilta Cattolica” (1885, Vol. I., p. 55), actually described the Inquisition as “a sublime spectacle of social perfection”; and the Jesuit, Schrader, supporting Pope Pius IX.’s “Syl- labus,” said that the Popes have never exceeded the bounds of their power, or usurped the rights of princes. Pope Clement IV., in 1265, sold millions of South Italians to Charles of Anjou, for a yearly tribute of 800 ounces of gold, and threatened excommunication if the first installment was late; whilst, if the second tarried, the entire nation would incur interdict (Raynaldus, p. 162).

One far-reaching claim is that every baptized person is, ipso facto, a subject of the Pope, willy-nilly, even though outside the Latin Church, and so subject to Papal Law (Dollinger, “The Pope and the Council,” p. 163). This claim was made by Pius IX. when writing to the Emperor of Germany, shortly after the downfall of Papal temporal power in 1870.

The Canonist, Kirchenrecht (7 Vols. Regensburg, 1855- 72, translated by G. Phillips), lays down the rule that “the Church has dominion over those without, as well as those within. The latter, by baptism, are sworn vassals. Anyone who rejects any doctrine is a ‘formal heretic.’ He need not belong to any sect. The Church is entitled to proceed to compulsion by virtue of the jurisdiction over baptized persons which belongs to her. She cannot tolerate heresy.”

Pope Leo XIII. urged that the scholastic philosophy of Thomas Aquinas be taught in all seminaries and schools. Aquinas taught that “Christ is fully and completely with every Pope in sacrament and authority.” The Pope can establish new confessions of faith; whoever rejects his authority is a “heretic” (Summa ii., 2, Q. 1, Art. 10; Q. xi., Art. 2, 3). Aquinas, using spurious writings of Cyril, taught that there is no difference between Christ and the Pope, and represented the Early Fathers as saying that the rulers of the world obey the Pope, as Christ (Opus xxxiv., xx. 540:580, Ed. Paris).

Bishop Cornelio Musso, of Bitonto, preaching in Rome, said: “What the Pope says we must receive as though spoken by God Himself. In Divine things we hold him to be God.” (Consciones in Ep. ad Rom, p. 606).

Pope Benedict XIV. said: “No one who is not Bishop of Rome can be styled successor of St. Peter” (De Synod Dioeces., II., i.).

Some of the Papal claims have been founded on, and are supported by, forgeries (see Dollinger’s “The Pope and the Council,” and Littledale’s “The Petrine Claims”). Yet the Canon Law containing those forgeries is still in use by Popes and Papists. Thus Cyprian’s alleged evidence in favor of Papal claims, admittedly a forgery, has actually been replaced in the text by F. Hurter, S.J., in his “Sanctorum Patrum Opuscula Selecta,” and is cited as genuine by Mr. Allnutt, in his “Cathedra Petri,” both of which works received Papal approval. Thus literary falsification is one of the characteristics or lawless features of the Papal system. It is a feature characteristic of ultramontanism, so much so that one may stigmatize Popery as systematized lies, to pseudos, and utterly opposed to the Truth as it is in Jesus; hence, the system is emphatically anomos, lawless.

Hence, when one reads such Papal Canonists as Ferraris, and finds them saying: “Ubi Papa, ibi Roma,” or styling the Bishop of Rome, “Pope of the Eternal City, the Apostolic Diocese’ (Baronius, An., 445, IX., X.), or “Pope of Old Rome, the Patriarchal See” (Synod of Constance, A.D. 859), one is prepared for almost any untruth whose object is the enhancement of the Pope’s claims to be what he is not, and never was. Even so, however, one can hardly conceive the possibility of lawless disregard for Truth, fact, and history, to soar to such heights as the subjoined extract from the Vatican Council of 1869-70’s “Decretum de Ecclesia.”

“The Holy Apostolic See and the Roman Pontiff hold the primacy over the whole world, and the Roman Pontiff himself is the successor of blessed Peter, Princes of the Apostles and the true Vicar of Christ, and Head of the whole Church, and Father and teacher of all Christians, and that full power was given to him in blessed Peter, by the Lord Jesus Christ, of feeding, ruling, and governing the Church Universal.”

For this claim, thus phrased, is precisely a paraphrase of the Holy Spirit’s delineation of the Antichrist, the the Sham Christ. Accompanied, as it was, by the blasphemous Decree of Papal Infallibility, it may be taken as God’s exposure of the “Lie,” the evidence forced by the Almighty from the “great voice” on seven hills, that he is “of his father the Devil,” for Satan was a liar from the beginning, and the Father of Lies; and Antichrist is Satan’s consummated mystery of iniquity (2 Thess. ii. 9; Rev. xi. 7; xvii. 8; John ix. 44; viii.44); his earthly spokesman; his Vicar.

(h) BURIAL OF HERETICS AND BOYCOTTING. REV. XI. 9.

It was predicted in Revelation xi. 9 that the burial of witnesses for Christ should be proscribed by Antichrist’s followers; and in Revelation xiii. 17 that trading should be forbidden to “heretics.”

It is distinctly laid down in the Decrees of the Third Lateran Council (Decret. Greg., Lib. V. tit. vii., cap. 8, as cited by Priest Bailly, tome iii, p. 139) that “heretics and those who defend and receive them shall be placed under anathema, and we prohibit under anathema that any shall presume to have them, or to entertain them in their house or in their territory, or to carry on any negotiation with them.* But if any die in this iniquity, neither under pretense of any privileges of ours granted to any such, nor under any other pretext whatsoever, let any offering be made for them, nor let them receive burial among Christians.”

* Liguori: Moral. Theol., Lib. VII., §188, etc., defines “greater excommunication,” “os, orare, vale, communio, mensa, negatur,” thus: “os,” all conversation, and intercourse, are forbidden; “orare,” all communion in spiritual things is forbidden; “vale,” all salutations are forbidden; “communio,” marriage, dwelling together, working at the same trade, walking together, are forbidden; “mensa,” all intercourse in food, society, or commerce. This ‘greater excommunication” was hurled by Pope Pius IX. in 1855, against Sardinia, for passing acts of toleration and reform.

Burial of Heretics is forbidden in Butler’s Catechism, Lesson XXI.: “What punishment has the Church decreed against those who neglect to receive the blessed Eucharist at Easter?” Ans.: “They are to be excluded from the House of God while living, and deprived of Christian burial when they die.” See also Dr. Douglas’ Catechism, Lesson XXI. They both quote the Council of Lateran, 21st Canon.

This is more clearly enforced in the Canon, Quicunque Haereticos, which declares: “Whosoever shall have presumed to give knowingly Christian burial to heretics—those who believe, receive, defend or favor them, let them know that they are placed under sentence of excommunication till they shall have made suitable satisfaction.

“Nor let them deserve the benefit of absolution till, with their own hands, they shall publicly drag from the tomb and cast out the bodies of damned persons of this sort, and let that spot be destitute of sepulcher for ever.” (Sext. Decret. Lib. V., tit. ii., cap. 2, Alexander IV., A.D. 1258. Corpus Jeris Canonici, tome ii. Magdeburgh, 1747).

Here we have a most conspicuous fulfillment of Revelation xi. 9 in medieval days. But modern fulfillments are at hand also. Thus the Belfast “News Letters” of December 15th, 1891, reported a case where the Protestant Rector of Christ Church, Bessbrook, found a coffin close to his house. It contained the corpse of a Protestant, named Patrick Kinney, who had been buried a week previously in the Romish Cemetery at Mullaglass. Because he had formerly been a Papist, but married a Protestant, and declined a Popish priest’s services when dying, the Papists, “with their own bands, dragged from the tomb and cast out the body” of this “heretic,” exactly as directed in the Corpus Juris!

In Canada, serious riots took place in 1875 over the burial of a man named Guibord, a member of the “Institut Canadien,” which had been denounced by the Popish Bishop of Montreal. Eight years previously, viz., in 1867, Guibord died, but the Popish authorities refused him burial in their cemetery. On appeal to the Law Courts and Privy Council, a mandamus was issued for burial in the Popish cemetery. It took eight years of costly litigation to obtain this; but the Papal authorities engineered a mob riot, which stoned the hearse, filled up the empty grave, and then the Popish Bishop of Montreal declared that if the body was buried by force, he would curse and interdict the ground it lay in! (“New York Times” and “New York Herald,” September 11th, 1875; “Times,” November 17th, 1875.) The object of this Bishop and the Papists was to assert the supremacy of Canon Law over British Law.

In 1877 a case occurred in Vineland, New Jersey, where Joseph Maggioli, a Romanist, had been buried in the Popish cemetery. The priest wrote to the widow, ordering her to remove the body, under pain of having it forcibly removed, and of prosecution for trespass. His name was P. Vivet. Owing to the indignation aroused the priest said that “he would have a line drawn round Maggioli’s grave, so that it should be left in unconsecrated ground” (“Boston Congregationalist,” 1877). In 1878 the “Montreal Witness,” of June 13th, reported “A Guibord case” in Cleveland. A Romanist, named Joseph Oberle, was a prominent Forester. The Popish priest refused to bury him in consecrated ground, although Oberle had paid for a plot of ground.

Owing to the high-handed action of the Popish Archbishop Vaughan, of New South Wales, in 1882, the “Times” (January 31st, 1882) used these words: “No quarter is given to any backsliding Romanist who presumes to have an independent opinion. He is put out of communion with his Church; and while denounced during his life, the rites of sepulture (burial) are withheld from his remains after death.”

In France, up to 1881, the Popish Law closed the cemetery gates against dead Protestants, Dissenters, unbaptised babes and suicides. During a debate in the Chamber, the Popish Bishop, Frappel, said: “One Protestant corpse in a Catholic cemetery would profane and desecrate the whole place.” One M.P. declared that Protestants had been forced to bury their dead in fields and gardens, owing to the priests. The Chamber was so disgusted with the conduct of the Papal party that it declared, by 348 votes to 120, that cemeteries in France should thenceforward be thrown open to dead Protestants (“Morning Advertiser,” 1881).

In Prussia the priests tried the same system, but under Bismarck’s regime got the worst of it. The Romish paper, “The Universe,” of February 11th, 1882, waxed furious in describing two cases, where priests were indicted and punished for not allowing burials in “consecrated ground.” In one case, that of a poor little baby, who had not been baptized, this Popish paper described it, like the adult, as an “infidel.”

This heartless and relentless cruelty is quite accordant with the teaching of the Catechism of the Council of Trent, which declares that: “All, unless regenerated through the grace of baptism, are born to eternal misery and everlasting destruction,” and that “infants, unbaptized, cannot enter Heaven.” (Donovan’s Translation, pp. 171, 172, 173, Dublin, 1820).

“The Times” of January 23rd, 1834, reported a shocking case at Carrickbeg, Co. Tipperary, where a crowd of fanatical Papists tried to prevent the burial of a corpse, “amid the most fearful imprecations on the deceased, and threats that they would dig up the body.”

The “Irish Times” of September 9th, 1921, described the taking over, by Benedictine nuns, of a former Protestant church at Kylemore. The Popish Archbishop of Tuam said that originally “the church was not built for proselytizing purposes. It was built as a place of Divine worship for Mr. Mitchell Henry’s own family, for all whose members the priests and people of the district had the greatest esteem.” The priests and people manifested this esteem by casting out Mr. and Mrs. Mitchell Henry’s ashes from the little church he had built, and where they had reposed in peace for years. It was only after the expulsion of their poor remains that the church could be dedicated by the Popish Archbishop to its new use-—as a Popish fane (church) (“The Catholic,” October, 1921; p. 109).

(i) REMOVAL OF THE “LET.” 2 THESS. II. 6, 7.

In 2 Thess. ii. 6 “what withholdeth” is neuter; in verse 7. “he who letteth” is masculine. Ere the man of the Apostasy could be “revealed,” the obstruction had to be removed “out of the way,” this obstruction being swayed by some Perpetual Person.

What was the restraint which, in Paul’s day, hindered the manifestation of the Man of the Apostasy? Tertullian, in the second century, said: “What is this restraining Power? What but the Roman State.” Similarly, Iraeneus affirmed that on the dismemberment of the Empire then in existence, the catastrophe would occur. So Cyril, Chrysostom, Theodoret, Augustine, Jerome in the fifth century— this lest adding, “Let us therefore say what all ecclesiastical writers have delivered to us, that when the Roman Empire is to be destroyed, ten Kings will divide the Roman world among themselves, and then will be revealed the Man of Sin”; “he who hindereth is taken out of the way, and we consider not that Antichrist is at hand.” So again, Justin Martyr and Hippolytus, the latter saying: “This [Rome] is the Fourth Beast, whose Head was wounded, and healed again; and Antichrist will heal and restore it.” Cyprian, likewise, spoke of the imminent proximity of Antichrist in his day.

It was this early Christian tradition that caused Christians to pray for the continuance of the heathen Roman Empire. Thus Lactantius: “Beseech the God of Heaven that the Roman State might be preserved, lest, more speedily than we supposed, that hateful tyrant should come.” So Chrysostom: “As Rome succeeded Greece, so Antichrist is to succeed Rome.”

This heathen imperial power was swayed by, and centered in a series of single persons, the Caesars—following one another in succession. History exactly corresponds to prophecy. When Constantine, the Roman Emperor, removed the seat of power from the seven-hilled city of Rome to Constantinople, then the restraint began to be removed which had prevented the Bishops of Rome from exercising temporal power or promulgating Anti-Christian claims. And when the last Western Caesar was forced to abdicate in A.D. 475, Rome ceased to be the “seat” of imperial secular power, and the Bishops of Rome began to put forward claims which exactly correspond with the predictions of Daniel, Paul, and the Apocalypse; for the restraint was ek mesou—”out of the way”—of the claimant to the seven- hilled city. As Cardinal Baronius (Annals, An., 324-30) admits, even during Constantine’s reign, the Bishops of Rome had amassed wealth, and before the end of the fourth century their wealth and splendor excited envy and wonder. Andreas (Bibl. P. Max., V., 623) asserts that “most of the ancient interpreters in the Church affirm that the Apocalyptic prophecies concerning Babylon regard Rome,” and that the Man of Sin, when he appears, “will be as Sovereign of Rome, and, in the opinion of some, in the Temple, or Church of God”—just as the earliest extant Commentary by Bishop Victorinus, in the third century, says: “The city of Babylon, that is, Rome; the City on seven hills, that is, Rome.”

Cardinals Bellarmine and Baronius admit that in the Apocalypse John “calls Rome Babylon,” and Bishop Bossuet likewise admits it. In the locality where prophecy places Antichrist, there history, with one accord, places the bishops of Rome—viz., in the city of Rome on the seven hills, in the capacity of successors of Caesar, not of Peter the Apostle.

(j) History’s AGREEMENT WITH PROPHECY.

And precisely at the period pointed to by prophecy, viz., on the removal of the Imperial power from the city of Rome, does history describe the rise into Anti-Christian power of the Bishops of Rome.

Dean Milman (“History of Latin Christianity,” Bk. iii., ch. iii.) said: “The foundation of Constantinople marks one of the great periods of change in the annals of the world. The removal of the seat of empire from Rome, . . . the absence of a secular competition, allowed the Papal authority to grow up, and develop its secret strength. By the side of the imperial power . . . constantly repressed in its slow but steady advancement to supremacy . . . The Pope . . . in any other city would in vain have asserted his descent from St. Peter.”

Gibbon (“Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” ch. xlix.): “The same character was assumed, the same policy was adopted by the Italian, the Greek, or the Syrian, who ascended the Chair of St. Peter; and, after the loss of her (Rome’s) legions and provinces, the genius and fortune of the Popes again restored the supremacy of Rome.”

Bishop Doyle, the Popish Controversialist (“Essay on the Catholic Claims,” sect. 5): “The seeds of decay were growing in the Roman Empire when the seat of government was removed to Constantinople . . . and Rome . . . now stripped of nearly all her wealth and glory, looked upon her Prelate as the last stay of her power. . . .”

Abbé H. Lacordaire (“Lettre sur le Saint Siege, p. 29): “If you would trace the temporal sovereignty of the Holy See to its source, you shall find that it has been derived from four concurrent circumstances . . . first, the decline of the Eastern Empire, which could no longer defend Rome against the barbarians; secondly, the ambition of the Lombard Kings, who desired to subject it [Rome] to their crown; thirdly, the protection of two great men in succession, Pepin and Charlemagne; finally, the love (!) which all the inhabitants of Rome felt towards the Sovereign Pontiff.”

Abbe Mably (Feller, in Art., Constantine): “It was determined by eternal (infernal?) interests, that Rome should henceforth have no other splendor than was derived from the Chair of her Pontiff.”

Count Le Maistre (“Du Pape,” Vol. I., p. 245): “While Rome was yet pagan, the Roman Pontiff bored the Caesars. The Emperors, who bore, amidst his titles, that of Sovereign Pontiff, could less endure a Pope than a competitor for his Empire. A hand unseen removed him from the Eternal City, to bestow it on the chief of the eternal (infernal?) Church. The same enclosure could not contain the Emperor and the Pontiff.

Mons. Masse (“Torts du Protestantisme envers les peuples”): “The choice of Byzantium by the first Christian Emperor permitted the Pontifical hierarchy to place above physical force a moral (!) power, distinct and separate, which displayed to all eyes its origin.”

Abbé du Pradt (“Concordat de l’Amérique avec Rome,” p. 70): “The removal of the Emperors to Constantinople gave rise to the greatness of the Popes.”

Gibbon (“Decline and Fall,” cxxi.) says that “the wealth and luxury of the Popes of the fourth century . . . represent the intermediate degree between the humble poverty of the Apostolic Fisherman and the Royal State of a Temporal Prince.”

In the year A.D. 595 Bishop Gregory I. of Rome denounced the title “universal Bishop”—claimed by his rival, of Constantinople—as Antichristian. Somewhere between A.D. 606 and 610 Bishop Boniface III. of Rome assumed that very title, accepting it from the Eastern Emperor Phocas, who was a usurper, a murderer, and had degraded Cyriacus, Petrarch of Constantinople, for a virtuous deed. The effect of this title upon the minds of ecclesiastics was soon apparent. As Jerome says: “When that which is temporal claims eternity, this is a Name of blasphemy.” Within forty years Theodore I., Bishop of Rome, assumed a fresh title, that of “Sovereign Pontiff.” He was the last Bishop of Rome whom bishops dared to call “brother.” A great and Antichristian change had manifestly been effected.* The “man of the Apostasy” had “revealed” himself, in his self-exaltation and pride.

* It is remarkable that 1,260 solar years, from A.D. 606-610, reach to the downfall (1870) of Papal territorial power; and 1,260 lunar years, from A.D. 646, reach to the Vatican Council of 1869, which proclaimed Papal Infallibility.

The exalted position now reached was inconsistent with dependence upon any earthly sovereign, so steps were taken to remove the custom that made the Bishop of Rome’s “consecration” dependent on the Roman Emperor’s prior approval of his “election” as Bishop. In A.D. 683 this restraint was removed by an Edict of the Emperor Constantine Pogonatus (Baronius, Epit. An. 684, i.).* The Pope was now independent, ecclesiastically as well as temporally.

*1,260 calendar years from A.D. 683 terminated in A.D. 1925; and in Solar years end in 1943. In Lunar years they ended in 1906.

Devastated by barbarians, who, ever since the fourth century, had ravaged the Roman Empire; deserted by its Sovereigns, Italy turned to the Popes, who, by force of circumstances, and by their own vaulting ambition, had become substituted for the Emperors—and so established the last form of headship over the Latin world, foretold of old.

Examine now Cardinal Newman’s words! He says, “While Apostles were on earth, there was the display of neither Bishop nor Pope” (p. 149, “Development, The Papacy.”)

Compare verse 3 of the prophecy in 2 Thess. ii.: The Man of Sin was not revealed when Paul the Apostle wrote.

The Man was to be “revealed in his own due time” (verse 6).

And Cardinal Newman says: “In course of time the power of the Pope displayed itself’ (p. 149, same Vol.).

There was something “withholding, or keeping back, the Man from appearing” in the first century (see verse 6).

And the Cardinal says: “The Imperial power, or Roman Empire, availed for keeping lack the power of the Papacy” (p, 151)

But was it generally admitted that the Empire’s power was that which hindered, or delayed, the Man of Sin?

Cardinal Newman says: “The withholding power, mentioned in Thess. ii. 6, was the Roman Empire. I grant this, for all the ancient writers so speak of it” (p. 49, “Discussions”),

Compare verse 5: “I told you these things, and now ye know what it is that withholdeth.”

“Only let the withholding party be taken away, or removed, then shall that wicked be revealed” (verse 7).

And Cardinal Newman says: “When the Imperial power had been removed to Constantinople (800 miles away!) then the Roman See came into a position of sovereignty” (p. 271, “Historic Essays,” Vol. ii.).

And again he says: “The Papacy began to form as soon as the Empire relaxed, . . . and further developments took place when that Empire fell’ (p. 152, “Development”).

Cardinal Newman says: “Pope Stephen VI. dragged the body of another Pontiff from the grave, cut off its head and three fingers, and threw it into the River Tiber. He himself was afterwards strangled in prison. Then the power of electing Popes fell into the hands of the licentious woman, Theodora, and her unprincipled daughters. One of these women advanced a lover, and another a son to the Popedom. The grandson, Octavian, ELEVATED himself to the Chair at eighteen, titled John XII.”

This is what Cardinal Newman tells us on p. 259 of his “Historic Essays”; and next page he says:—

“Pope John XII. was carried off by a blow received during his intrigues. Boniface VII. after his elevation, plundered the Church of St. Peter, and fled to Constantinople; Benedict IX. was Pope at twelve, and became notorious for adulteries and murders.

Such are a few of the most prominent features of Church History; when the world lay in wickedness, Simon the Sorcerer lording it over the Church, whose bishops and priests were given to fornication” (p. 260).

Cardinal Manning, “The Temporal Power,” p. 126; “The temporal power of the Supreme Pontiff was only in its beginning; but about the seventh century it was firmly established.” Page 16: “For 1,200 years the Bishops of Rome have reigned as temporal princes.” Page 127: “For these 1,200 years the peace . . . of Europe has been owing solely in its principle to this” (!). Page 182: “From that hour, which I might say was 1,500 years ago, or, to speak within limit, I will say was 1,200, the Supreme Pontiff has been a true and proper Sovereign.”

(Daniel vii. 25: “They shall be given into his hand, until a time, and times and half a time” i.e., three and a half times, or 1,260 years.)

(k) GRADUAL RISE INTO POWER.

When first proclaimed in words only, the Papal system was repudiated by Gregory I.—as already stated. On that theory, the Pope has the plenitude of Power, all other bishops are only his servants and auxiliaries, from him all power is derived, and he i s concurrent Ordinary in every diocese. So Gregory understood the title, “Ecumenical Patriarch,” and would not endure that so “wicked and blasphemous a title” should be given to himself or anyone else (Janus, “The Pope and the Council,” p. 84). But from the assumption of that “blasphemous title,” by Boniface III., right onwards to the promulgation of Papal Infallibility in 1870, the career of the Papacy has been one long, incessant, and ever-augmenting assumption of Antichristian “names of blasphemy,” and the putting forth of claims based on those names.

As there is no “let” or “hindrance” in existence, these claims continue to the present hour. They endanger the peace of the world, because they involve the disruption of kingdoms, the overthrow of states, and the re-establishment —by force—of that Papal territorial power, (emphasis mine) which in 1870 was rightly taken away from the Papacy by popular vote. These claims establish beyond the region of controversy, that the Papacy is the Antichrist, for they are as opposed to the Spirit of Christ as are the falsehoods, the forgeries and the pride on which they are based.

(l) FALSE BASIS AND SUPERSTRUCTURE.

That the Papacy is the outcome of belief in a falsehood is shown by the prediction in 2 Thess. ii. 11: “for this cause (i.e., because they received not the love of the truth) God sendeth them a working of error, that they should believe The Lie—to pseudos.”

What the Papacy is to-day is best described by an ex- Jesuit, Graf Paul Von Hoensbroech, for fourteen years a Jesuit priest, who, in his preface to “The Papacy in its influence upon Society and civilization,” says: “The Papacy . . . is the greatest, the most fatal and, at the same time, the most successful system of error to be found in the world’s history. The Papacy—that huge error system . . . ultramontanism is a perfectly organized system, high, dry, and broad, close-jointed, highly finished in every respect.”

In “Ultramontanism, its Bane and its Antidote,” he said: “Ultramontanism is a Secular Political System which, with and under the cloak of religion, arrogates to itself worldwide political and temporal power.”

In the former work he also says: “The Papacy, in its pretensions to be a Divine institution, deriving its existence from Christ . . . is surrounded with thousands of lies emanating from its defenders.”

Mr. J. M. Capes, in his “Reasons for Returning to the Church of England” (pp. 110-111), says: “A system which depends for success upon falsification of history is, ipso facto, a system which produces a disbelief in the value of clear and unflinching honesty of statement in the affairs of life. Accordingly, whenever the Roman ideas of Church government establish themselves, they bring with them the spirit of intrigue, and a distaste for honest, unflinching truth-telling.

The Rev. E. S. Foulkes, once a Romish priest, says in his “Difficulties of the Day,” pp. 145-153: “Gradually the conviction dawned upon me that this wondrous system . . . as it exists in our day, was a colossal Lie; a gigantic fraud; a superhuman imposture; the most artistically contrived take-in for general credence, for specious appearances, ever palmed upon mankind.” ‘Where Satan works most, it is precisely there that he is most anxious to keep farthest out of sight. I say, then, of the Roman system, that it is an agglomeration of lies, reposing on a basis of truth.”

In 1891 Leo XIII. delivered an Allocution to the Cardinals in Secret Consistory (“Tablet,” December 19th, 1891), in which he pretended that all sorts of “enemies” were “on every hand visible,” seeking to “assign boundaries to the spiritual power of the Pope, who holds it direct from God”* – where observe to pseudos—The Lie. Upon this the “Standard” of December 17th, 1891, very properly commented by pointing out its falsity: “When Leo XIII. bewails the limitations on his spiritual kingdom, he either says the thing that is not, . . . or, he is really betaking himself to lamentation because he cannot extend his spiritual kingdom, and wield . . . the temporal arm in vindication of it. If this claim means anything at all, it implies a demand to be empowered to suppress heresy, and therefore to resort to persecution.”

* In his Encyclical “De Unitate,” Leo XIII, said: “What Jesus Christ had said of Himself, we may truly repeat of ourselves.”

“At the bottom of these recurring Papal jeremiads (a speech or literary work expressing a bitter lament) is the unwillingness of the Papacy to resign itself to the loss of temporal sovereignty, and the settled resolve to go on agitating for its recovery by all the means and all the expedients at its disposal.”

Here the “Standard” most correctly exposes the Papal falsehood, which represents the Italians as its “enemies,” because they oppose its evil demands and claims to use force. As this paper pointed out: “in other words, the Pope’s Allocution, which is ostensibly a spiritual utterance, is a political manifesto.’ That is, it is a Lie.

The Right Hon. W. E. Gladstone, in his “Rome: Newest Fashions in Religion,” showed incontestably from Papal Documents, from the “Syllabus” and “Encyclical” of 1864, and from the “Speeches” of Pius IX., that the claims of the Pope are a series of violent tirades and political harangues disguised as religious utterances, all having for their object the restoration of Papal territorial power, in order to possess the means of enforcing the Papal Will, and of suppressing all opposition by force. The mendacity accompanying these utterances is fully set forth by Mr. Gladstone, himself an expert in the art of “camouflage.” No more conspicuous an example of the prevailing falsehood of Papal remarks can be conceived than Pius IX.’s description of the atrocious Kingdom of Bomba (this seems to be referring to Sicily. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferdinand_II_of_the_Two_Sicilies), as a Kingdom of “repose and tranquility,” for which he “prays,” a “Kingdom of peace and prosperity.” As Mr. Gladstone indignantly observed: “This is the language in which the Pope is not ashamed to speak of a Government founded upon the most gross and abominable perjury, cruel and base in all its details to the last degree.”*

*Archbishop Bagshawe did not hesitate to say: “There is no Christianity outside of the Catholic Church”; so also states Pius X.’s Catechism, thus placing Christianity inside a colossal lie.

(m) FALSEHOODS.

The language of falsehood is inseparable from the Popedom. This falsehood is manifested in every sort of way; in the description of the Pope as “the Lamb of the Vatican,” for example: “The Living Christ,” “The Vicar of Christ,” “The Most Holy Lord,” “His Holiness,” “Our Father,” et cetera; as well as in the forgeries so ably exposed by the learned Dr. Dollinger, in his “The Pope and the Council,” viz., the Isidorian Decretals of the ninth century; that “huge fabrication”; the Hildebrandine Forgeries of the eleventh century, which used the Isidorian forgeries to further Papal Absolutism; the “earlier Roman forgeries” towards the end of the fifth and beginning of sixth centuries, when “the compilation of spurious acts of Roman martyrs” began, and was “continued for some centuries.” These forgeries included “the fabulous story of the conversion and baptism of Constantine, invented to glorify the Church of Rome, and make Pope Sylvester appear a worker of miracles.” “Then the inviolability of the Pope had to be established, and the principle that he cannot be judged by any human tribunal.” Towards the end of the sixth century a fabrication was undertaken in Rome, the full effect of which did not appear till long afterwards, viz., the interpolation of a falsehood in Cyprian’s book on the unity of the Church, which represented Cyprian as teaching that “the Church is built on the Chair of St. Peter.” An old catalog of Roman bishops was interpolated for an ulterior object, afterwards carried out in the “Liber Pontificalis.” “It is the first edition of 530, which is chiefly to be reckoned as a deliberate forgery, and an important link in the chain of Roman inventions and interpolations.”*

*Hallam’s “View of the State of Europe during the Middle Ages,” 1869, p. 348, says: “Upon these spurious decretals was built the great fabric of Papal supremacy over the different national Churches . . . the imposture is too palpable.”

About the middle of the eighth century, the famous “Donation of Constantine” was concocted at Rome, based on the earlier fifth century legend, whereby the Pope is described as lord and Master of all Bishops, and having authority over the four “thrones” of Antioch, Alexandria, Constantinople, Jerusalem; and as having received Italy and the Western Provinces from the Emperor. It is upon this forgery that the Pope’s claim to territorial power rests. The earliest reference to this pretended gift of Constantine occurs in Pope Adrian’s letter to Charlemagne in A.D. 777; though Popes had, since A.D. 752, spoken of “restitution” of Italian towns and provinces to St. Peter or to the Roman Republic. As Dollinger remarks: “Such language first became intelligible when the [forged] ‘Donation of Constantine’ was brought forward to show that the Pope was the rightful possessor, as heir of the Roman Caesars in Italy…. .”

“Twenty years later, the need was felt at Rome of a more extensive invention. So a document was laid before Charlemagne in Rome, professing to be his father Pepin’s “gift” or promise of territory to the Pope. This forgery assigned all Corsica, Venetia, Istria, Luni, Moselica, Parma, Reggio, Mantua, and the Duchies of Spoleto and Benevento, and the Exarchate of Ravenna (“Liber Pontificalis,” ii., 193, Edition Vignol).

There have unquestionably been some falsifications in privileges granted to Popes by Emperors later than Charlemagne —such as the “pact” of Louis the Pious, in A.D. 817 —an interpolation of the eleventh century. So, again, with the privileges of the Emperors, Otho I., in 962, and Henry II. in 1020. All kinds of other forgeries are traceable to Rome. As “Acts of Martyrs” had been fabricated there earlier, so from the tenth century, false documents were fabricated wholesale at Rome (“Le Grotte Vaticane, Roma, 1639,” pp. 505-510; Jaffé, “Regesta,” p. 936).

The most potent instrument of Papal machination was Gratian’s “Decretum,” issued in the twelfth century, from Bologna. In this the Isidorian forgeries were combined with other Gregorian writers’ fabrications, as well as with Gratian’s own. This work displaced all older collections of Canon Law, and became the fount of knowledge for all “scholastic theologians”! Forgery was herein added to forgery—all alike enhancing the claims of the Papacy.

About A.D. 1570 this compilation of falsehoods was “corrected,” at the desire of the Pope; yet to-day it forms the Codex for all canonical authority! For instance, the false principles that the Pope is superior to Law, and that all Church property is his, that clerics are exempt from civil law by Divine ordinance.

(n) FALSIFICATION OF SCRIPTURE.

Not only so, but texts of Scripture have been deliberately falsified in furtherance of Papal aims. Thus Innocent III. (1198-1216) altered Deuteronomy xvii. 12 in the Vulgate, as to mean whoever does not submit to the decision of the High Priest (whose place the Pope claims to hold) is to be killed (“Decret. per Venerabilem,” “Qui filii sint legitimi,” 4,17). Pope Leo X. quoted the text as corrupted, in a Bull, giving a false reference to the Book of Kings instead of Deuteronomy, to prove that whoever disobeyed the Pope must be put to death (Pastor Aeternus, Hardouin, Concil., IX. 1826).

In the thirteenth century, a new fabrication appeared, affecting dogmatic theology and education. It is known as the “Dominican Forgeries,” because composed by a Dominican monk, who concocted a catena of spurious passages from Greek Councils and Fathers. They professed to be eight hundred years old, and were at once used by Pope Urban IV. to prove that the “Apostolic Throne” is the sole authority in doctrinal matters (Raynaldus, Annal. Ann., 1263, 61). Urban sent the document to Aquinas, who knew no Greek, and from the Latin translation made by Buonaccursia, the Dominican, invented the doctrine of Papal Infallibility. One of his phrases was: “Christ is fully and completely with every Pope in sacrament and authority.” Thus on the basis of fabrication by a Dominican monk, Aquinas built up his Popedom, which ever since has put forth its blasphemous claims of Infallibility and Absolutism.

Lord Acton, Regius Professor of History at Cambridge, a Roman Catholic, said: “The passage from the Catholicism of the Fathers to that of the modern Popes was accomplished by willful falsehood; and the whole structure of traditions, laws, and doctrines that support the theory of infallibility and the practical despotism of the Popes, stands on a basis of fraud” (“North British Review,” October, 1869, p. 130).*

*In a letter to Mr. Gladstone quoted at p. lv. of Mr. H. Paul’s Introductory Memoir to Letters of Lord Acton to Mary Gladstone he said: It not-only promotes, it inculcates distinct mendacity and deceitfulness. In certain cases it is made a duty to lie.”

John Henry Shorthouse (author of John Inglesant) said: “The Papal Curia is founded upon falsehood, and falsehood enters, consciously or unconsciously, willingly or unwillingly, into the soul of every creature that comes under its influence.” (Preface to Rev. A. Galton’s “Message & Position of the Church of England,” 1899, pp. 13-14.)

Leo XIII., by a special “Encyclical on Scholastic Philosophy,” urged that Aquinas’s teaching should be used in all schools and seminaries; so that Falsifications of history permeate the entire curriculum of scholastic education in the Popedom. The entire system is based on a Lie, the lie that the Apostle Peter was “Prince of the Apostles” and “Bishop of Rome,” and that his successors are “Vicars of Christ.” It is permeated through and through with lies, which are known to be such, but are deliberately utilized to bolster up false claims. No more evident identification can be afforded than this, that the very names the Popes assumed are false from beginning to end.

(o) THE TITLES OF THE POPES ALL FALSE.

To the end of the fourth century they called themselves “Vicars of Peter,” but since the fifth, “Vicars of Christ” — the former title being as false as the latter, though not so blasphemous. The name “Pope,” or Father, was in A.D. 500 “appropriated to the Roman Pontiff (Gibbon, vii., 37), it having formerly been the title of all bishops alike. Tertullian, in one if his Treatises, speaks of the Roman bishop in his own time calling himself by the heathen title, “Pontifex Maxinus,” as well as “Episcopus Episcoporum.” Cyprian and Augustine both rejected the false claim of the Bishop of Rome in regard to Christ’s statement: “Thou art Peter, and on thee I will build My Church”; but the Bishop of Rome undeviatingly claimed the Primacy because Rome was “the See of the Prince of the Apostles,” a wholly mendacious claim based on falsehood. To maintain this, the Acts of Nicene Council were falsified (Hardouin, i., 469-485), and other Forgeries of Councils were made in support.

But it is decisively and distinctively the false title, “Vicar of Christ,” that emphatically establishes the Papacy as the “Antichrist.” This title was given by a Roman Council to Gelasius, Bishop of Rome, 5th century: “We behold in thee Christ’s Vicar” (Hardouin, ii., 946, 947).*

* Cardinal Bellarmine, in his Treatise on the Roman Pontiff (De Rom. Pont. Lib. ii. Cap. XXXI., Ingoldstadt, 1839), said: “Pope: Father of Fathers; the Pontiff of Christians, High Priest, the Vicar of Christ, the Head of the Body, that is of the Church, the foundation of the building of the Church; the Father and Doctor of the faithful; the Ruler of the House of God; the Keeper of God’s Vineyard; the Bridegroom of the Church; the Ruler of the Apostolic See; the Universal Bishop.”

And in his “De Conciliorum Auctoritate Lib. ii, Cap, XVII.” “All the names which are given in the Scriptures to Christ (where it appears that He is superior to the Church)—all these names are given to the Pope.”

(p) “WAR WITH THE SAINTS.”

The general principle by which Popery is governed is thus laid down by some of its authorized organs: “We are the children of a Church which has ever avowed the deepest hostility to the principles of ‘religious liberty.’ If it would benefit Catholicism, he (the Papist) would tolerate you; if expedient, he would imprison you, banish you, fine you; possibly, even, he might hang you . . .” (“Rambler,” September, 1851).

“Catholicism is the most intolerant of creeds. It is intolerance itself ” (Ibid).

Cardinal Manning (“Sermons on Ecclesiastical Subjects”) stated: “The Holy See is ultramontane, the whole Episcopate is ultramontane, the whole priesthood, the whole body of the Faithful throughout all nations . . . all are ultramontanes. Ulltra- montanism is Popery, and Popery is Catholicism.”

Count Montalembert (Letter, dated Paris, February 28th, 1870) cited the Archbishop of Paris as saying: “The new ultramontane school leads to a double idolatry—the idolatry of the temporal power, and of the spiritual power. The new ultramontanes . . . have abounded in hostile arguments against all liberties”; and Dr. Dollinger (“The Pope and the Council”) declared that “Ultramontanism, then, is essentially Papalism,” or, as Montalembert expressed it, “Absolutism of Rome.”

Now this shows not only the general principle that governs Popery in its relationship to Protestantism or Religious Liberty, but also the fact that, given an opportunity, it would enforce, as of yore, that principle, by the same means it adopted “in the good old days.”

It is therefore important to know precisely what those means were, and how it used them in the plenitude of its power. As shown elsewhere, the Notes on Matthew xiii. 29 (which have been incorporated in a class-book for use at Maynooth, entitled “Menochis”) teach that “heretics” may lawfully and properly be put to death, as common malefactors (see also Douai Bible, Coyne, Dublin, 1816); and “by public authority, either spiritual of temporal, may and ought to be chastised or executed.” The Romish Archbishops, who authorized these Notes, were well aware of the meaning of their teaching, and were well acquainted with the history of the past, i.e. of the Persecutions and Crusades, the Massacres and the Dragonnades, whereby millions of Christians were slaughtered and put to death, by every form of cruelty, from the twelfth to the eighteenth century. They were not speaking at random, or inculcating empty formula. Ranke’s “History of the Popes” tells us that these “Crusaders” boasted: “We have spared neither age nor sex; we have smitten everyone with the edge of the sword” (I., 32).

The “War with the Saints” predicted in Daniel vii. 25; Rev. xi. 7, xiii. 7, as made by “the Beast,” commenced in a general way, under Pope Alexander III.’s Council at Tours, A.D. 1163, which denounced the Bible-reading Albigenses as “heretics,” prohibited buying from or selling to them, and proscribed them. This was followed by the Decree of the Third Lateran Council, A.D. 1179, under the same Pope, against all so-called “heretics,” refusing them Christian burial, and forbidding any to harbor them. In A.D. 1183 Pope Lucius III. issued a Bull against “heretics” of every sort, and ordering the “Inquisition” to suppress them. In 1198 Innocent III. wrote Epistles to various Prelates, charging them to extirpate “heresy,” and to employ the arms of princes and people. He then sent “Legates” as Inquisitors to Toulouse, and not long afterwards proclaimed a “Crusade” against the “heretics.”

The third Canon of the fourth Council of Lateran, in a.d. 1215, urged more zeal in the extirpation of heresy, the secular powers being expressly enjoined to carry out the behests of the ecclesiastic, vassals being absolved from allegiance to any prince who refused, and crusaders being rewarded like Crusaders in the Holy Land. In A.D. 1227 the Council of Narbonne followed on the same lines, and then that of Toulouse, in which children were compelled to denounce parents as heretics, and the Scriptures were forbidden to the laity. Council after Council on the same lines followed, up to Gregory IX.’s ferocious Bull in a.d. 1236. The fact of the commencement of this Papal War against Christians is strongly marked in History, even as the Jesuit Gretzer, in his “Prolegomena, induciae Tudensis succedaneos,” admits. It was a Papal war of extermination of all witnesses for Jesus, and leveled against Holy Scriptures.

The same spirit and procedure were manifested in England from 1360 to 1380 against Wyclif and his followers, and in Bohemia —some forty years later—against Huss and Jerome; furious “war” being waged against individuals, such as Savonarola, in Italy, from 1464 to 1498, as well as elsewhere against Bohemians, Waldenses, Taborites and United Brethren. Popes and Councils, priests and people all joined in this “war,” and racks and gibbets, fire and sword were deemed fit weapons against Christians. The story of the murder of the Waldenses under Pope Innocent VIII., and of the Christians of Val Louise in High Dauphiny, is a recital of atrocities calculated to make one’s blood curdle. In 1478 the Inquisition was “reformed,” so as to become more efficacious as an instrument of persecution and murder. Llorente, the historian of this “reformed” Inquisition, computes that between 1478 and 1517, 13,000 persons were burnt alive, and 169,000 tortured. At the beginning of the sixteenth century the Papal War with the saints had succeeded in reducing them to silence by means of fire, sword, torture and persecution.

During the sixteenth century the Reformation took place, and, in order to stamp it out, the Papacy summoned the Council of Trent, which continued its labors from 1545 to 1563, ending with a unanimous shout of “Anathema to Heretics,” having decreed all sorts of decrees and canons, all containing curses upon anyone who refused to accept their unscriptural teaching. Session XXV. decreed that every clause and word enacted by that Council, under Popes Paul III., Julius III. and Pius IV. established “the authority of the Apostolic See always inviolate.” In other words, all that was ever enacted as Papal Law or claimed as the authority of the Pope is ever enduring and unchangeable. Every barbarous enactment against “Heretics,” every power and privilege to break oaths, and to dispense from law, or to absolve subjects from loyalty, everything in Rome’s Canon Law still remains in force today.

In A.D. 1572 took place St. Bartholomew’s massacre, and in A.D. 1588 the Spanish Armada, both of them phases of the “war against the saints,” followed by the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, 1685, and the Dragonnades, which caused such misery to the French Huguenots. In Ireland there took place the fiendish atrocities, in 1640-42, of the Irish massacre of Protestants; whilst in Scotland the Protestant Covenanters suffered every kind of persecution and martyrdom. During Mary’s short reign of five years, no less than some three hundred British martyrs were burnt at the stake; the Gunpowder Plot, and other seditious movements, leading up to the English Rebellion and overthrow of the Stuart dynasty, all being but phases of this incessant “war” on the part of Rome—against liberty, Bible truth, and the “saints” or witnesses for Christ, i.e., Protestants.

The Revelations of the Italian Revolution in Rome in 1848, when the Inquisition buildings were broken open, show incontestably the late date on which this murderous institution—an institution established wholly by the Church of Rome under Papal sanction—was at -work, in this terrible “war”; a war waged all over the world to the present hour, as Missionary Societies’ reports unceasingly testify.

Such is a mere sketch of a long-enduring and remorseless “war,” as recorded in history. It is the due fulfillment of Prophecy. If we enter into particulars, the case becomes still more conclusive against Rome, as it shows that no system that has ever existed has such a record of murder and inquisitorial cruelty towards Christians. Neither Pagan Rome nor Mohammedanism can compare with the record of Papal Rome. It is “facile princeps,” (Latin meaning easily the first or best) and unique in that respect, as its “war” has been ever waged against Christians because of their faith in Christ, and belief in Holy Writ.