Revelation 9:20-21. The Unrepentant State of Western Christendom

This is the continuation of The Last Prophecy: An Abridgment of Elliott’s Horae Apocalypticae.

A.D. 1057-1500.1

[20] And the rest of the men which were not killed by these plagues yet repented not of the works of their hands, that they should not worship devils, and idols of gold, and silver, and brass, and stone, and of wood: which neither can see, nor hear, nor walk:

[21] Neither repented they of their murders, nor of their sorceries, nor of their fornication, nor of their thefts. (Rev 9:20-21)

THE REMARKABLE EVENTS which we have noticed in these last lectures, consummated by the destruction of the eastern third of Roman Christendom, were well calculated, we should have imagined, to arrest the other portions of the professing Church in their course of error and ungodliness and to have induced repentance and reformation. But the subsequent history of the West affords evidence to the accuracy of that prophetic announcement which had been given to the Evangelist, how that the long-prevailing doctrinal perversions and moral iniquities of men would continue wholly unaffected by these warning judgments of their Lord.

It was an awful, but a true picture — “The rest of the men repented not.” Compared with the history and fate of her sister in the East, the case of the Western Church resembled that of treacherous Judah, whose guilt was even more unpardonable than that of backsliding Israel.

The announcement made in the vision is twofold; 1st, as implying the grievous corruptions which had existed in Western Christendom during the progress of these woes; and secondly, as declaring the continuance of the same after the fall of the Greek Empire.

[1] The period embraced by the advance and decline of the Turkish woe, — “the hour, day, month, and year,” — from A.D. 1057 to 1453, is well worthy of observation in the general history of Christendom. The kingdoms of Western Europe had been slowly assuming those territorial forms and limits which, in the main, they have ever since retained. The Christian remnant in Spain, after having for a length of time confined the Moors within the kingdom of Grenada, had in the year 1452, under Ferdinand and Isabella, completely conquered and expelled them. The central Frank or French kingdom had subordinated to itself by degrees the several principalities which had been broken off. England, which, previous to the Norman conquest, had been subdivided into small states, had become united in government, and had attached Ireland and Wales to its dominion. Both France and England, thus aggrandized, had begun that rivalry of centuries which, while it gave occasion to prolonged wars, served at the same time to develop their national resources. The elective Germanic Empire, after a partial diminution of strength and glory through its wars with Rome and Switzerland (the latter having become independent), now under the house of Austria extended on the one side over Hungary and Bohemia, and on the other to the Baltic Sea. Italy, after witnessing for two or more centuries the short but brilliant course of the Lombard republics, had been subdivided into several small states. The temporal sovereignty of the Bishops of Rome had become firmly established through Central Italy, and was now fully recognized in European polity as the ecclesiastical state, or, as it was in part singularly called, the patrimony of St. Peter.

Moreover, with the political progression of these great European confederations there had been a steady advance from barbarism to comparative civilization. Chivalry had exercised a beneficial influence on outward manners. Internal trade, and still more maritime commerce, had led the way to civil liberty; so that many free towns had been established, and feudal servitude had gradually disappeared. Intellectual energy had also awakened from a long slumber. Universities had risen up. Oxford and Cambridge, Paris and Montpellier, Bologna and Padua, Salamanca and Prague, were crowded with students. A yet more extended range was opened for learning when in A.D. 1440 the art of printing was invented. The scholars of Greece, fleeing before the Turkish woe, had brought their Stores of classic lore before the Western literati, who now eagerly engaged in the study, and everywhere knowledge and science was pursued.

Again religions zeal was a feature of the times, if such term may be applied to the Crusaders, and to those who exercised their powers in building those magnificent ecclesiastical structures, cathedrals, etc., which still remain and excite the admiration of all beholders in England, France, Germany, and Italy. Certainly with those who raised them such zeal could not be called lukewarm.

Thus much for the progress in power, freedom, refinement, intellectual energy, and religious zeal of the western division of Europe. Would we next inquire what the character of religion had been during the same period? The Scripture in the few lines before us tells the tale. The first clause says, “Men repented not of worshiping demons.” The term demons was used in St. John’s time, both in Roman literature and Scripture language, to express the heathen gods, and also those malignant evil spirits which entered into or possessed demoniacs. Such being its double meaning, the Apostle might infer, from the words of the vision, that there would be established in the nominally Christian Church a system of demonolatry, the counterpart of that of Greece or Rome — a fact, as before observed, for which he was prepared by the gradual apostasy from the faith of Christ’s mediation and atonement; that imaginary beings would be worshipped, and the spirits of dead men deified; also that moral virtues would be attributed to them, in about the same proportion of good and bad, as to ’the heathen gods; that, like them, they would be supposed to act as guardian spirits and mediators; and that this false system would be, in fact, an emanation from hell, as was its precursor, malignant, hellish spirits being the suggestors, actors, and deceivers in it. All this the Scriptural meaning of the word demon might well imply.

Of the fulfillment of the prophetic declaration no well-informed Protestant is ignorant. The decrees of the seventh General Council, which established image worship, remained in force during this period, more and more superseding the spiritual worship of the one great God and Christ in his mediatorial character. The evil was not confined to more mental worship, inasmuch as visible images of different value were made, so as to suit all grades, from the palace to the hovel; and before these all men, high and low, rich and poor, laics (pertaining to a layman or the laity) and ecclesiastics, did, in contempt of the positive command of God, bow down and worship, just as did their Pagan forefathers. Added to this, as might be gathered from the vision, the grossest dissoluteness prevailed alike among priests and people. Indulgence for crimes not even to be named might be purchased for a few pence. This system of indulgences, the journeyings of both sexes to the same places to perform the same penances, generally at the shrine of some saint, the compulsory celibacy of the clergy, the increase of nunneries, and the practice of auricular confession — these are named by various writers as some of the means and incentives which tended too surely to include licentiousness amongst the effects of superstition.

When we feel wonder at such practices being admitted amongst professed Christians, we must call to mind that the Bible was at that time almost unknown, and that the priests supported the religion they taught by magical deceits and sorceries, whereby they worked upon the imaginations of their credulous followers. Who that has ever read the history of these times knows not of the impostures through which miracles were said to be wrought; — relics of saints made to perform wonderful cures; — images that could neither see, nor hear, nor walk, made to appear as though possessed of human senses, and as restoring sight to the blind, strength to the lame, and hearing to the deaf? Who knows not the stories invented of purgatory, and the happy effects of masses and prayers purchased on earth upon the souls suffering therein? This was the work, not of ignorance, but of deliberate deceit. These were the sorceries specified among the unrepented sins of Papal Rome. Amongst these were also included thefts. But wherefore all these impositions? Doubtless, while ambition, pride, and blind superstition combined, each in large measure, the love of money was yet the root of the evil. By payment to the priest, full license was obtained for sin, and impunity guaranteed, both then and thenceforward. In order to appease God, it was only necessary to make pilgrimages, and to lay offerings on the shrines of the saints; all then was well. In A.D. 1300, Pope Boniface established a pilgrimage to Rome, instead of to Jerusalem, by virtue of performing which every sin was to be canceled, and the pilgrim’s salvation ensured. The sale of Church dignities and of episcopal licenses for the grossest immoralities swelled the funds of the Church. But enough upon this subject!

To these is added the charge of murders. The blood of their fellow-men — of Petrobrussians, Catharists, Waldenses, Albigenses, Wickliflites, Lollards, Hussites, Bohemians, — not dissentient heretics only, but the genuine disciples of Christ, was shed abundantly during the latter half of these four hundred years. It was guilt enough to incur death in that they were opposed in anywise to the pretensions of the Church of Rome.

In the twelfth century a few persons began to read and explain the Bible. The cry of heresy was forthwith raised, and the extermination of the whole people urged as a meritorious act. The innocence of these Waldenses was admitted; but the Book itself was condemned by Pope and priesthood, and partially suppressed.

In the fourth Lateran Council, A.D. 1215, a Crusade was proclaimed against them, and plenary absolution of all sin from birth to death was promised to such as should perish in the holy war. “Never,” said Sismondi, “had the cross been taken up with more unanimous consent.” Never, we may add, was the merciless spirit of murder exhibited more awfully in all its horrors. It was followed by the Inquisition, having Gregory IX. for its apparent author, — the spirit of hell its unseen one. That horrid tribunal, from which no man could feel safe, was supported by the princes of the West. The same murderous spirit was manifested from A.D. 1360 to 1380 against Wickliffe in England, and against Jerome and Huss in Bohemia, who, forty years after, endeavored to revive the spirit of true religion, and were martyred. But more of these hereafter.

Such is a sketch of the so-called religion of this period in Western Europe; so characteristic was the description, “idolatry, sorceries, fornications, thefts, murders,” as identified with its state during “the hour, day, month, and year,” up to the fall of the Greek Empire.

There are some who would paint those times as ages of faith, and others as periods of illumination in the Church; but the religion of the majority of such persons is obviously that of the imaginative and external, and not what the Bible recognizes of heart-cleansing, practical godliness. There are who extract passages from mystic writers of the day adorned with some beauty, and more or less of truth, and hold them up as specimens of the spirit of the age. But the appeal must be made to history for the truth; and history accords in every iota with the wonderful prophetic description in the text as expressing the real state of faith and conduct existing at that time.

[2] “Men repented not.” We have seen what history records as to the state of morals and religion up to the fall of Constantinople; and as the prophetic voice indicates that after that woe men continued unrepentant as before, so, turning to history, we shall find it. Not a word is there about reformation or repentance, but we do find every sin continued. Demonolatry increased. In A.D. 1460 came the renewed use of the rosary (see footnote), a mechanical method of devotion specially used with reference to the Virgin, which soon became the rage in Christendom, and was embraced alike by clergy and laity, being consecrated by Papal sanction. In A.D. 1476 Pope Sixtus gave sanction to an annual festival in honor of the Virgin’s immaculate conception. The canonization of saints continued. In A.D. 1460 the enthusiast Catherine of Sienna was sainted. In 1482 Bonaventura, a blasphemer, who dared to parody the psalter by turning the aspirations there addressed to God into prayers to and praises of the Virgin Mary, was added to the list. In 1494 Archbishop Anselm was canonized by Pope Alexander VI., who on that occasion declared it to be the Pope’s duty thus to choose out and hold up the illustrious dead for adoration and worship.

Sorceries and thefts increased. Rosaries were for sale. Each canonization brought devotees and offerings to a new miracle-working shrine. Nor did Rome accord canonization without itself first receiving payment. ” With us,” says a Roman poet of the age, “everything sacred is for sale: priests, temples, altars, frankincense, the mass for the living, prayers for the dead, yea, heaven and God himself.”4 The pilgrimage to Rome was decreed by Paul II. to take place every twenty-five years, thus accelerating the return of that lucrative ceremony. Relics were sold to those who were not able to travel, and indulgences retailed by numerous hawkers; with which latter practice the name of Tetzel was, at the opening of the sixteenth century, infamously associated, presenting the crowning example of thefts and sorceries.

Impurity, chiefly among the priesthood, glaringly advanced. The Popes led the way. Alexander VI. was a monster in vice. “All the convents of the capital were houses of ill-fame;”5 and one German bishop, according to Erasmus, declared “that 11,000 priests had paid him the tax due by them to the bishop for each instance of fornication.” We may not enter further on this subject.

Finally, murders ceased not. Anti-heretical crusades were proclaimed on a large scale. The Bohemians and Waldenses were the chief victims. Paul II., who had been elected Pope in order to check the Turks, turned his energies against the Bohemians, and offered to the Hungarian king the crown of Bohemia as a reward if he should succeed in exterminating the Hussites. This was only attained at last by dividing the poor persecuted people amongst themselves; and after seven years of unsuccessful war this civil strife proved their most severe suffering.

In the years 1477 and 1488 Innocent VIII. commanded all archbishops, bishops, and vicars to obey his inquisitor, and engage the people to take up arms with a view to effect the extermination of the Waldenses; promising indulgence to all engaged in such war, and a right to apply to their own use all property they might seize.

Then 18,000 troops burst upon the valleys; and had not the sovereign, Philip of Savoy, felt compunction and interfered, the work of extinction would have been completed, even as it was at Val Louise in High Dauphiny. “There the Christians,” says the historian, “having retired into the caverns of the highest mountains, the French king’s lieutenant commanded a great quantity of wood to be laid at the entrances to smoke them out. Some threw themselves headlong on the rocks below; some were smothered. There were afterwards found 400 infants stifled in the arms of their dead mothers. It is believed that 3000 persons perished in all on this occasion in the valley.” Is Rome changed?

In 1478 the reform, as it was called, of the Inquisition took place, the Pope and the king of Spain agreeing in the arrangement, whereby it became a still more murderous instrument for persecution than before. In the first year alone 2000 victims were burnt! It is computed that from its reorganization up to 1517 there were 13,000 persons burnt by it for heresy, 8700 burnt in effigy, and 169,000 condemned to penances. It was in 1498 that Savonarola, a Dominican, was burnt at Florence for preaching against the vices at Rome, and this too by order of Papal emissaries. We might say, Look at Florence now; but we shall have more to speak on this subject hereafter.

Thus does history, upon the clearest authorities, abundantly bear out the truth of the statement that after the fall of the Greek Empire “men repented not of their idolatry, sorceries, fornications, thefts, and murders.” Relative to idolatry, there is a singular proclamation by Mohammed II., issued in A.D. 1469, which will show how the Christian worship of that day was regarded by Mohammedans. “I, Mohammed,” he says, “son of Amurath, emperor of emperors, prince of princes, from the rising to the setting sun, promise to the only God, Creator of all things, by my vow and by my oath, that I will not give sleep to mine eyes, etc., till I overthrow and trample under the feet of my horses the gods of the nations, those gods of wood, of brass, of silver, of gold, or of painting which the disciples of Christ have made with their hands.”

So closed the fifteenth century. Hopelessly wretched seemed the then state of the Church, the more so because remedies for bettering its condition had been tried and failed. At the commencement of these four and a half centuries Charlemagne tried, by augmenting the temporal power of the priesthood, to soften and civilize the minds of the people under its control; but pride, ambition, covetousness, and immorality, rife among the leaders, were not likely to lead to reform amongst their followers. The attempted remedy only increased the evil during the twelfth century. In the thirteenth century the Dominican and Franciscan orders rose up, proclaiming that riches had caused the corruption of the clergy; and binding themselves by a vow of poverty, they set forward to preach the Gospel of Christ. For nearly two centuries the tide of popularity set in in favor of the friars. They, it was said, exhibited simplicity and self-denial in practice; they alone were the true ministers of Christ. At length this delusion also vanished; the lying fables palmed on the credulous were unmasked. But it was found more difficult to get rid of these orders than to establish them. The Pope gave them encouragement, and, who could resist the Pope? So matters were not improved.

Councils were called, and it was hoped that this would be a sovereign remedy. The Council of Constance in A.D. 1414, showed that it was ready to assist the Papal tyranny by its decree against Huss and Jerome. Again, in the middle of this century, in the Councils at Florence and Ferrara, the Pope was decreed to be superior to any council; and at the close of the century it was almost universally received that, as God on earth, he could not err and might not be controlled. So little was success attendant on this effort at reform.

Literature was next tried. But what could it do?

Without the Bible it might make men infidels but not Christians, and at that time the Bible was unknown. The superstitions believed by the people were fostered on the priest’s part for interest-sake, though known by these to be false; and the penalties against heresy forbade any public objection on the part of the laity.

The character given of the last Pope of the fifteenth century was in a measure applicable to the cardinals and hierarchy of Rome gathered round him. It was an atheist priesthood; and its hypocrisy was deliberate, systematic, avowed, and unblushing before the face of God and man.

Thus the various efforts for reform acknowledged to be needed had apparently failed. As the sixteenth century opened, there were some who still looked for change even from councils. In fact, supported by the French king, but opposed by the Pope and cardinals, one reform council was gathered at Pisa; but it was too weak to oppose the current of evil. Apostasy from their God and Saviour constituted the essence of the disease; and for remedy nothing but the republication of his own gospel of grace, and the power of his Spirit accompanying it, could effect the cure.

Dark and dreary was this time to the true but secret Church of the “hundred and forty-four thousand.” Amidst these days of desolation one and another had lifted up the voice of witness (as we shall treat of in a subsequent lecture on “the witnesses”), and many prayed and wailed, in hopes that He, whom to know is life and light, would reveal himself and interfere for his Church. But time went on; the first watch of the night, the second,and the third watch passed, and their strength was spent. Their hopes waxed fainter. Persecuted, wasted, scattered, it seemed as if “God had forgotten to be gracious,” and that the promise that the gates of hell should not prevail against his Church had become a dead letter. But was it really so? Did St. John so see the end of the Church and the triumph of the foe? No! He says, “I looked, and saw another mighty angel descend.” That intervention of the Lord for his people so long waited and prayed for was come, and the next scene in this wonderful drama is that of the REFORMATION.

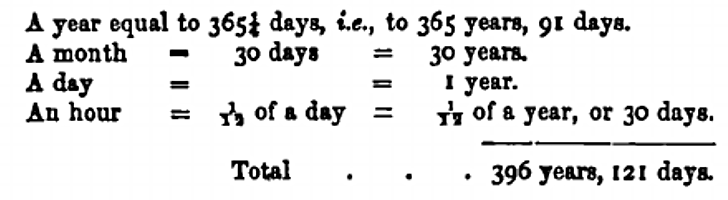

To the foregoing we may add a word or two as to the state of the English Church during these last centuries. The tale is soon told. It partook of the general corruption. One or two instances will suffice relative to a part of the charges made against Rome. Thomas a Becket’s shrine was one of the places of pilgrim-resort. A jubilee was celebrated to his honor, and plenary indulgence given to such as visited his tomb, of whom 100,000 have been registered at a time. In the Cathedral at Canterbury were three shrines, one to Christ, one to the Virgin Mary, and one to the saint. The offerings on each, in A.D. 1115, were computed as follows: —

So much for Demonology! Wickliffe was then raised up, who protested against the errors, and exposed so ably the fraud of the friars as to cause them to be detested throughout the land, where they had gained immense influence. In A.D. 1305, Edward I. wrote to the Pope to have the Bishop of Hereford canonized because “a number of miracles had been wrought by his influence.”

Footnote:

The rosary is a string of beads used by Roman Catholics in devotion, often as an act of penance. Each large bead being counted, the Pater Noster or Lord’s Prayer is repeated; and, after each small one, an address to the Virgin. A Romish catechism, approved by the Popes, has this question and answer: “Why repeat the Ave after the Lord’s Prayer? Answer. — That, by the intercession of the Virgin Mary, I may more easily obtain from God what I want.” There are ten Aves to each Pater Nestor (Latin for our Father).↩

Continued in Revelation 10:1-3. Intervention Of The Covenant Angel