This is the continuation of The King James Version: Part II The Efficacy of the Word

The Forerunner and the Biblical Shepherd Theme

The first part of Isaiah has 39 chapters and the second part 27, which parallel the numbers of Old Testament books (39) and the New Testament books (27). The Bible has a total of 66 books, the same as the number of Isaiah chapters, 66. The second part of Isaiah begins at chapter 40, and the rest of the book is consistently joyous and triumphant. Given this decided change of tone, the beginning of Isaiah 40 has always been significant, a warning or blessing, the announcement of one who would serve as the forerunner of the Messiah promised in Isaiah 7 and 9.

The first 10 verses should give us goosebumps, an involuntary reaction to the truth of the news being announced, a truth so powerful that no nation, no ecclesiastical power can dampen, shade, or hide it –

KJV Isaiah 40 Comfort ye, comfort ye my people, saith your God. 2 Speak ye comfortably to Jerusalem, and cry unto her, that her warfare is accomplished, that her iniquity is pardoned: for she hath received of the Lord’s hand double for all her sins. 3 The voice of him that crieth in the wilderness, prepare ye the way of the Lord, make straight in the desert a highway for our God. 4 Every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill shall be made low: and the crooked shall be made straight, and the rough places plain: 5 And the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together: for the mouth of the Lord hath spoken it. 6 The voice said, Cry. And he said, What shall I cry? All flesh is grass, and all the goodliness thereof is as the flower of the field: 7 The grass withereth, the flower fadeth: because the spirit of the Lord bloweth upon it: surely the people is grass. 8 The grass withereth, the flower fadeth: but the word of our God shall stand for ever. 9 O Zion, that bringest good tidings, get thee up into the high mountain; O Jerusalem, that bringest good tidings, lift up thy voice with strength; lift it up, be not afraid; say unto the cities of Judah, Behold your God! 10 Behold, the Lord God will come with strong hand, and his arm shall rule for him: behold, his reward is with him, and his work before him.

When John the Baptist identified with this passage, it meant he was announcing the immediate advent of the Messiah. This alerted the entire region to the upcoming event, which had been discussed since the miraculous appearance of the Star of Bethlehem. From the Star appearing before them all, to the boy Jesus talking to the elders at the Temple, which was a second presentation after His circumcision, people hoped. The nation, captive to Rome, felt the divine energy of the Tanakh coming true – the arrival of the Virgin’s son, the Son of David, the Messiah, the Prince of Peace!

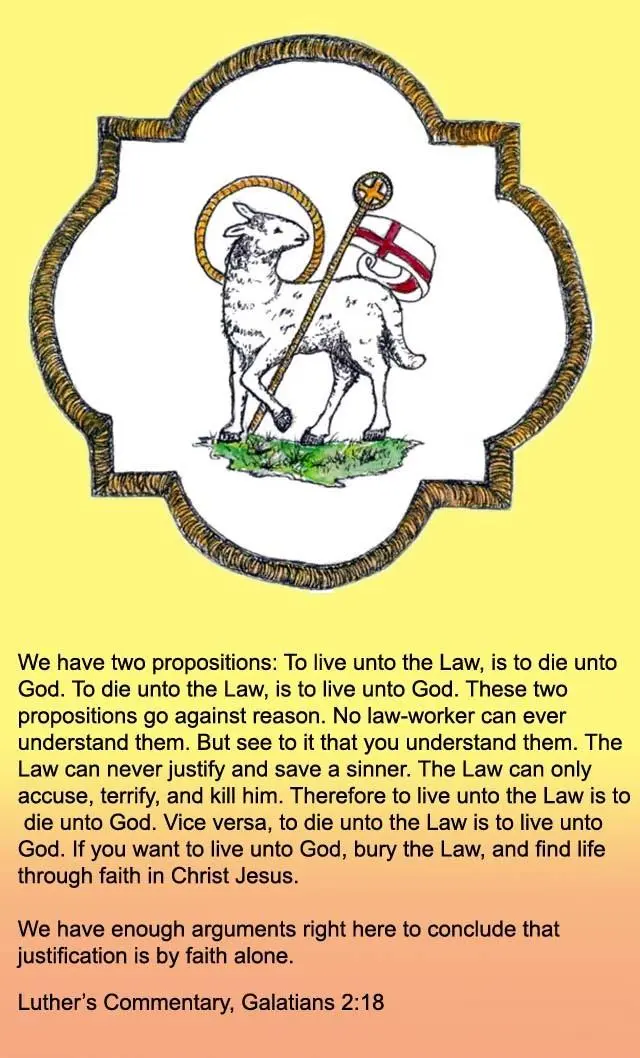

This event is not condensed into verses on war, slaughter, strength, and victory, but shepherding.

KJV Isaiah 40:10 Behold, the Lord God will come with strong hand, and his arm shall rule for him: behold, his reward is with him, and his work before him. 11 He shall feed his flock like a shepherd: he shall gather the lambs with his arm, and carry them in his bosom, and shall gently lead those that are with young.

This continues the Two Natures of Christ theme. The Almighty God will come, as promised, His work before Him, as the Good Shepherd. Parallel to Psalm 23 and John 10, He will feed His flock, the way a shepherd does, providing protection from enemies, food, and pure water. He will watch over the lambs, carry the newborns close to Him, and gently lead those still nursing. Jesus Christ will reveal His Messianic role by attacking the enemies of the Gospel with His Word and by protecting, with His Word, those who trust in Him and need His guidance, nurture, and safety.

The Writings

The Psalms – All Things Must Be Fulfilled Concerning Me

In the Law of Moses, the Prophets, and the Psalms

KJV Luke 24: 44 And he said unto them, These are the words which I spake unto you, while I was yet with you, that all things must be fulfilled, which were written in the law of Moses, and in the prophets, and in the psalms, concerning me. 45 Then opened he their understanding, that they might understand the scriptures.

People usually see Jesus Christ in the Torah, the Books of Moses, though many of my graduate students in Old Testament are surprised at how much Gospel is there, how many ways the Son of God is revealed before His Incarnation. One senior pastor said he never realized this, and he preached on the Old Testament all the time. The Gospel revelations come from God’s intent and Luther’s unified teaching of the Bible as the Book of the Holy Spirit, all parts in one unified Truth.

The prophets are filled with many Gospel Promises, but some readers become obsessed with Law and condemnation without giving a place for God’s mercy and grace. Unfortunately, the Psalms are another battle ground for the unbelieving scholars, who ply their trade as if it is their duty to teach the threadbare rationalistic theme of the Old Testament being on its own and not relating to the New Testament – except as the New Testament writers chose to quote it. One “conservative” cleverly downplayed Jesus in the Messianic Psalms, in a one-volume NIV commentary from Concordia Publishing House, so it is important to deal with them. Nothing is clearer than Psalm 22 beginning with the cry of Jesus from the cross, which was mocked by the crowd. The entire Psalm is a direct prophesy of His Atoning death.

Concordia Publishing House also featured Reading the Psalms with Luther, 1993. Luther wrote, p. 56:

The 22nd psalm is a prophecy of the suffering and resurrection of Christ and a prophecy of the Gospel, which the entire world shall hear and receive. Beyond all other texts, it clearly shows Christ’s torment on the cross, that He was pieced hand and foot and His limbs stretched out so that His bones could have been counted. Nowhere in the other prophets can one find so clear a description. It is indeed one of the chief psalms.

KJV Psalm 22

My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me? why art thou so far from helping me, and from the words of my roaring?

2 O my God, I cry in the day time, but thou hearest not; and in the night season, and am not silent.

3 But thou art holy, O thou that inhabitest the praises of Israel.

4 Our fathers trusted in thee: they trusted, and thou didst deliver them.

5 They cried unto thee, and were delivered: they trusted in thee, and were not confounded.

6 But I am a worm, and no man; a reproach of men, and despised of the people.

7 All they that see me laugh me to scorn: they shoot out the lip, they shake the head, saying,

8 He trusted on the Lord that he would deliver him: let him deliver him, seeing he delighted in him.

9 But thou art he that took me out of the womb: thou didst make me hope when I was upon my mother’s breasts.

10 I was cast upon thee from the womb: thou art my God from my mother’s belly.

11 Be not far from me; for trouble is near; for there is none to help.

12 Many bulls have compassed me: strong bulls of Bashan have beset me round.

13 They gaped upon me with their mouths, as a ravening and a roaring lion.

14 I am poured out like water, and all my bones are out of joint: my heart is like wax; it is melted in the midst of my bowels.

15 My strength is dried up like a potsherd; and my tongue cleaveth to my jaws; and thou hast brought me into the dust of death.

16 For dogs have compassed me: the assembly of the wicked have inclosed me: they pierced my hands and my feet.

17 I may tell all my bones: they look and stare upon me.

18 They part my garments among them, and cast lots upon my vesture.

19 But be not thou far from me, O Lord: O my strength, haste thee to help me.

20 Deliver my soul from the sword; my darling from the power of the dog.

21 Save me from the lion’s mouth: for thou hast heard me from the horns of the unicorns.

22 I will declare thy name unto my brethren: in the midst of the congregation will I praise thee.

23 Ye that fear the Lord, praise him; all ye the seed of Jacob, glorify him; and fear him, all ye the seed of Israel.

24 For he hath not despised nor abhorred the affliction of the afflicted; neither hath he hid his face from him; but when he cried unto him, he heard.

25 My praise shall be of thee in the great congregation: I will pay my vows before them that fear him.

26 The meek shall eat and be satisfied: they shall praise the Lord that seek him: your heart shall live forever.

27 All the ends of the world shall remember and turn unto the Lord: and all the kindreds of the nations shall worship before thee.

28 For the kingdom is the Lord’s: and he is the governor among the nations.29 All they that be fat upon earth shall eat and worship: all they that go down to the dust shall bow before him: and none can keep alive his own soul.

30 A seed shall serve him; it shall be accounted to the Lord for a generation.

31 They shall come, and shall declare his righteousness unto a people that shall be born, that he hath done this.

Psalm 2 is another one of many Messianic psalms. Luther wrote about its prediction that the Savior would suffer:

Psalm 2 is a prophecy of Christ, that He would suffer, and through His suffering become King and Lord of the whole world. Within this psalm stands a warning against the kings and lords of this world: If, instead of honoring and serving this King, they seek to persecute and blot Him out, they shall perish. This psalm also contains the promise that those who believe in the true King will be blessed.(Reading the Psalms with Luther, p. 17. )

Those Jewish believers who have been converted by the Gospel to the Christian Faith recognize that many passages that seemed obscure and strange were the Scriptures preparing them for the New Testament. What else could “Kiss the Son” mean in verse 12, but to stop raging against the Truth and follow Him?

Psalm 2

1 Why do the heathen rage, and the people imagine a vain thing?

2 The kings of the earth set themselves, and the rulers take counsel together, against the Lord, and against his anointed, saying,

3 Let us break their bands asunder, and cast away their cords from us.

4 He that sitteth in the heavens shall laugh: the Lord shall have them in derision.

5 Then shall he speak unto them in his wrath, and vex them in his sore displeasure.

6 Yet have I set my king upon my holy hill of Zion.

7 I will declare the decree: the Lord hath said unto me, Thou art my Son; this day have I begotten thee.

8 Ask of me, and I shall give thee the heathen for thine inheritance, and the uttermost parts of the earth for thy possession.

9 Thou shalt break them with a rod of iron; thou shalt dash them in pieces like a potter’s vessel.

10 Be wise now therefore, O ye kings: be instructed, ye judges of the earth.

11 Serve the Lord with fear, and rejoice with trembling.

12 Kiss the Son, lest he be angry, and ye perish from the way, when his wrath is kindled but a little. Blessed are all they that put their trust in him.

Figure 7 Henry Eyster Jacobs wrote this brilliant explanation of how we should view the Scriptures.

Abraham in the New Testament

John 8

Nothing demonstrates the unity of the Testaments – and the clarity of the Gospel – more than Abraham in the New Testament. Readers should ask why this is so and why so many who wear the academic gown ignore this truth.

One example alone sets the stage while the other citations show the strength of this connection between the Genesis patriarch and the divinity of Christ. The Gospel of John is a good place to start, because the Fourth Gospel assumes knowledge of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, giving us additional knowledge of the three- year public ministry of Christ and His message.

In John 8, Jesus spoke of His relationship with His Father, and the importance of faith in Him as the will and the voice of His Father above.

KJV John 8:31 Then said Jesus to those Jews which believed on him, If ye continue in my word, then are ye my disciples indeed; 32 And ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free.

This created a division, because Jesus spoke of faith in Him while His opponents taught the virtue of descent from Abraham.

KJV John 8: 33 They answered him, We be Abraham’s seed, and were never in bondage to any man: how sayest thou, Ye shall be made free? 34 Jesus answered them, Verily, verily, I say unto you, Whosoever committeth sin is the servant of sin. 35 And the servant abideth not in the house for ever: but the Son abideth ever. 36 If the Son therefore shall make you free, ye shall be free indeed. 37 I know that ye are Abraham’s seed; but ye seek to kill me, because my word hath no place in you. 38 I speak that which I have seen with my Father: and ye do that which ye have seen with your father.

The Apostle Paul made much of this distinction in Galatians and Romans, so the earlier division needs to be kept in mind.

39 They answered and said unto him, Abraham is our father.

Jesus is teaching faith in Him while they speak of works. Today the works are the teachings of the synod’s patriarchs, opposing the Scriptures, not faith in Jesus Christ but obedience to the current yet always-changing local dogmas.

39b Jesus saith unto them, If ye were Abraham’s children, ye would do the works of Abraham. 40 But now ye seek to kill me, a man that hath told you the truth, which I have heard of God: this did not Abraham.

As Jesus and the Jewish leaders debate, it is clear that He is directing them to God the Father through Him, but that only upsets them more.

56 Your father Abraham rejoiced to see my day: and he saw it, and was glad. 57 Then said the Jews unto him, Thou art not yet fifty years old, and hast thou seen Abraham? 58 Jesus said unto them, Verily, verily, I say unto you, Before Abraham was, I AM. 59 Then took they up stones to cast at him: but Jesus hid himself, and went out of the temple, going through the midst of them, and so passed by.

This remarkable statement teaches the Two Natures of Christ and His pre-existence as the Son of God before His incarnation. Jesus’ response is humanly impossible, and can only come from God Himself. He is the divine Voice from the Burning Bush, existing before Abraham and yet speaking of Abraham believing in Him as the future Messiah, the foundation of the descendants more numerous than the stars in the sky.*

* Timothy Ferris, in his classic book Galaxies, has photos of one area of the sky where countless galaxies swirl, each one containing millions of stars. Genesis 15.

Genesis 15:5b God brought Abraham outside and said, “Look now toward heaven, and tell the stars, if thou be able to number them: and he said unto him, So shall thy seed be. 6 And he believed in the Lord; and he counted it to him for righteousness.”

Abraham did not believe in his own empire, because no empire has lasted forever and had countless inhabitants. He believed in God’s Promise of the future Messiah, whose Kingdom of God would grow forever until the end of time.

Matthew

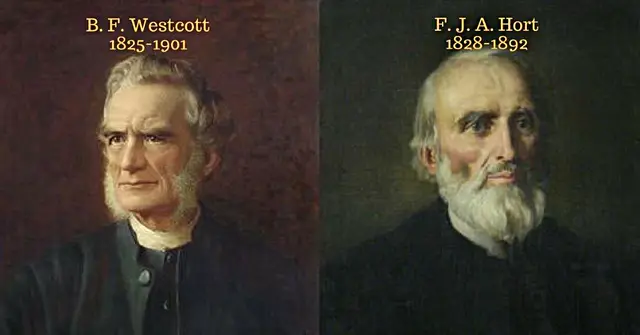

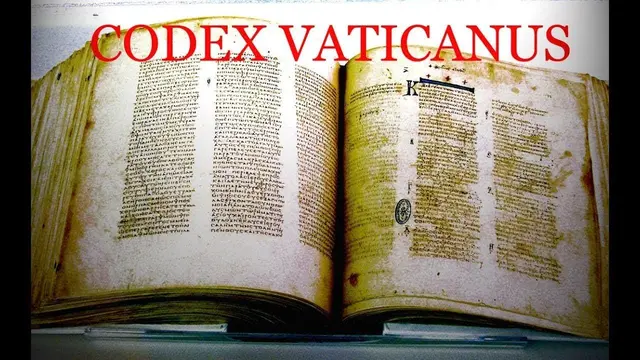

The modern scholars pick up heavy volumes to cast at the Gospel of John, because they do not know or fear God. They have Tischendorf, Hort, Barth, Bultmann, and Nida for their fathers, so they despise the simple, inspired Scriptures – and ignore Abraham the father of faith, who is named in Matthew 1:1 –

The book of the generation of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham.

This is summed up in Matthew 1:17 –

KJV So all the generations from Abraham to David are fourteen generations; and from David until the carrying away into Babylon are fourteen generations; and from the carrying away into Babylon unto Christ are fourteen generations. 18 Now the birth of Jesus Christ was on this wise:

The reference to Abraham as the father is found in Matthew 3, so we can see how this concept was elaborated in John 8

KJV Matthew 3:9 And think not to say within yourselves, We have Abraham to our father: for I say unto you, that God is able of these stones to raise up children unto Abraham. 10 And now also the axe is laid unto the root of the trees: therefore, every tree which bringeth not forth good fruit is hewn down, and cast into the fire.

This is another expression of John 8 – God’s Word can raise up children of Abraham from stones, and we can rejoice that the Gospel created children of God from the tattooed and naked pagans of Europe, the Picts and Celtics, the ancestors of many of us. Already during Jesus’ ministry, the Word converted pagans into believers, children of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, but many blood descendants would be cast into outer darkness, Mathew 8:10-12.

Luke

Zacharias – “His name is John.”

Luke reveals many truths in a few verses. The holy prophets have existed since the world began. These prophets taught the ancient Gospel Promises of protection for those who trust in the covenant of Abraham. God swore He would deliver us from our enemies so we could serve Him without fear – in holiness and the righteousness of faith – all our days.

KJV Luke 1: 70 As he spake by the mouth of his holy prophets, which have been since the world began: 71 That we should be saved from our enemies, and from the hand of all that hate us; 72 To perform the mercy promised to our fathers, and to remember his holy covenant; 73 The oath which he sware to our father Abraham, 74 That he would grant unto us, that we being delivered out of the hand of our enemies might serve him without fear, 75 In holiness and righteousness before him, all the days of our life.

The central figure is not Adam or Moses but the patriarch Abraham, who believed God’s Promise of an everlasting and ever-growing Kingdom, and that was counted as righteousness. This happened before Abraham was circumcised, forgiveness without any form of Law, civic or religious.

Children from Stones

As Luther wrote, the Holy Spirit is very stingy with words, so when we see them repeated in the Gospels, those words and verses are especially important. John the Baptist taught this, as quoted above in Matthew. The concept of children from stones is repeated in Luke’s Gospel. The last of all the prophets, more than a prophet – John the Baptist thundered –

KJV Luke 3: 8 Bring forth therefore fruits worthy of repentance, and begin not to say within yourselves, We have Abraham to our father: for I say unto you, That God is able of these stones to raise up children unto Abraham.

Nothing is more lifeless and inert than a stone, so this metaphor is a clear reminder of the efficacy of God’s Word, since we are no more tuned to God’s Promises than stones are – until the Gospel is preached to us, as babies at baptism and later in life when the Promises come to us and give us a new life. The reference of John the Baptist to Abraham is related to the patriarch’s faith, not his blood.

Daughter of Abraham – Luke 13:16

The woman healed in Luke 13 is a “daughter of Abraham,” so the synagogue ruler raged that she was healed on the Sabbath, when everyone must rest and not work. Jesus shamed the ruler, and the people rejoiced. The distinction is made again, about faith in Him versus the works of the Law.

KJV Luke 13: 28 There shall be weeping and gnashing of teeth, when ye shall see Abraham, and Isaac, and Jacob, and all the prophets, in the kingdom of God, and you yourselves thrust out.

On Judgment Day, the patriarchs of faith and all prophets will be in the Kingdom of God, but the works saints (Luther’s term) will be tossed out.*

* Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress is full of examples of faith versus the false notions of works. He obtained a copy of Luther’s Galatians Lectures and read the book more than any other book except the Bible. Those two books are found in the Lutheran Library, as printed books and PDFs, and as Understanding The Pilgrim’s Progress and Understanding Luther’s Galatians as my contributions.

Luke 16 – Jesus Parable of Lazarus, the Rich Man, and Father Abraham

Two great contrasts teach us the Gospel in Luke 16:19- 31. The rich man is clothed in rich fabrics and eats a banquet of delicacies daily. Poor Lazarus is a dying cripple laid at the rich man’s gate, so he might beg some food from the rich man. But all Lazarus got, day after day, was the attention of scavenger dogs licking his open sores. The poor beggar died and was carried by the angels to Abraham’s bosom. But the rich man was carried into Hell, and he saw Lazarus far away, in the bosom of Abraham. His debate with Father Abraham, a noble title, is especially noteworthy because this is the Son of God teaching clearly about forgiveness and eternal salvation.

The rich man, who had everything in life and banquets daily, pleaded “Father Abraham, have mercy on me, and send Lazarus, that he may dip the tip of his finger in water, and cool my tongue; for I am tormented in this flame.”

Father Abraham said, “Son, you had everything in life, he only had evil; now he is comforted, and you are tormented.”

The rich man tried another approach, sending Lazarus to his five brothers, who were in need of this warning and his advice. The dying beggar is now a professor or preacher who might command the attention of the brothers who were so much like the rich man. Abraham countered, “They have Moses and the prophets. Let your brothers hear them.” This is a thunderbolt from heaven, meant to shake up everyone neutral or against the faith of Jesus. Moses and the prophets are sufficient for teaching people about the Savior, forgiveness of sin, and eternal life. The Old Testament alone is enough Gospel and is in fact an abundance of Gospel Promises and Blessings.

The rich man had a flawless final counteroffer – “But if someone would rise from the dead, everyone would listen.”

The final response, spoken by the Savior, is weighted down with meaning – “If they do not pay attention to Moses and the prophets, neither will they listen to One if He rose from the dead.” Two doctoral students in theology at Notre Dame were furious with me for saying, “Of course I believe Jesus actually rose from the dead.” They said, “There is no talking with you about anything.” Rejection of the Old Testament Gospel blinds people to the simple, obvious truths of the New Testament.

Abraham’s name appears six times in this parable, because Father Abraham is the Father of Faith in the Savior. Abraham is named eleven times in John 8.

Luke 19 – Little Zacchaeus

Zacchaeus was short, but he was rich from extorting taxes from his countrymen to support the Roman occupation. He received a percentage, so he was motivated to harvest tax money in abundance. His rush to see Jesus suggests that he had heard much, felt deeply troubled by his greed, and raced to get a view from a sycamore tree. The Word of Jesus was certainly effective, so he slid down the tree, bark flying, to host Jesus.

KJV Luke 19:5 And when Jesus came to the place, he looked up, and saw him, and said unto him, Zacchaeus, make haste, and come down; for today I must abide at thy house.

The people, who were sinners, murmured against Jesus going to the house of Zacchaeus, an open sinner. As a sign of his contrition, he offered to give money to the poor and pay back his overcharges.

KJV Luke 19:9 And Jesus said unto him, This day is salvation come to this house, forsomuch as he also is a son of Abraham. 10 For the Son of man is come to seek and to save that which was lost.

Zacchaeus is a son of Abraham by faith in Jesus Christ.

Abraham in Galatians and Romans

If Abraham is a major figure in John and Luke, then he is dominant in Galatians and Romans. Galatians is first in composition, and Romans is first as the doctrinal statement. Paul wrote Galatians with great energy to refute the false claims of needing the Jewish law to be real Christians. The argument is clear in both books – we are justified by faith in Jesus Christ, which is impossible through the Law.

The teaching of Justification by Faith is so clear in Galatians that only the apostates can miss what it means. Abraham was not circumcised when he was promised a son who would begin a line leading to the Savior. How could the false teachers entice the Galatians to engage in a practice that Abraham did not need?

KJV Galatians 3: 3 Are ye so foolish? having begun in the Spirit, are ye now made perfect by the flesh? 4 Have ye suffered so many things in vain? if it be yet in vain.5 He therefore that ministereth to you the Spirit, and worketh miracles among you, doeth he it by the works of the law, or by the hearing of faith? 6 Even as Abraham believed God, and it was accounted to him for righteousness. 7 Know ye therefore that they which are of faith, the same are the children of Abraham.

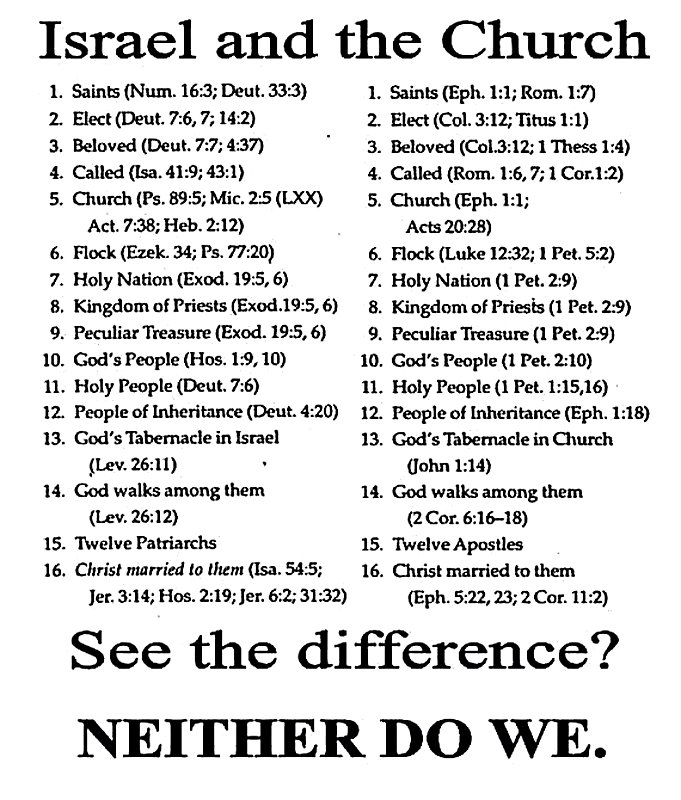

The mainstream, liberal, apostate mainline denominations – including ELCA, WELS, LCMS, and the ELS – teach universalism by claiming that the entire world is absolved from sin and forgiven, without faith. This is clearly contrary to the Scriptures from Genesis onward. What ties the two Testaments together is the faith of Abraham in Christ, his example of trusting God’s Promises.

KJV Galatians 3:8 And the scripture, foreseeing that God would justify the heathen through faith, preached before the gospel unto Abraham, saying, In thee shall all nations be blessed. 9 So then they which be of faith are blessed with faithful Abraham.

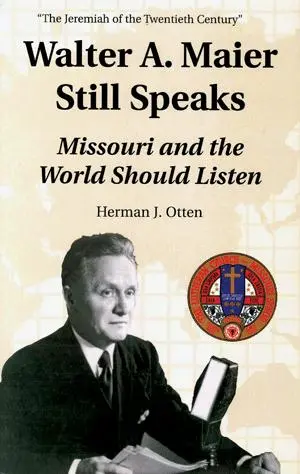

Dr. Walter A. Maier (PhD, Semitics, Harvard) created a radio ministry by teaching the inerrancy of the Bible and Justification by Faith*. His LCMS academic heirs teach the opposite of both – Biblical errors and justification without faith. The example of Abraham, so often repeated in the Bible, has no impact on their dogmatics. Nevertheless, the Scriptures connect Abraham to faith in every possible example.

* Galatians 2: 16 Knowing that a man is not justified by the works of the law, but by the faith of Jesus Christ, even we have believed in Jesus Christ, that we might be justified by the faith of Christ, and not by the works of the law: for by the works of the law shall no flesh be justified. The first bolded – δια πιστεως ιησου χριστου – not faith in Christ but the faith of Christ. The second bolded – ινα δικαιωθωμεν εκ πιστεως χριστου – the faith of Jesus. Neither one is faith in Jesus, a fact skipped by modern translators. The KJV is correct with “faith of Christ.” Yes, He was both man and God, and He had faith in God the Father. Salvation comes to all believers from the faith of Christ to our faith, from faith to faith.

KJV Galatians 3:11 But that no man is justified by the law in the sight of God, it is evident: for, The just shall live by faith. 12 And the law is not of faith: but, The man that doeth them shall live in them. 13 Christ hath redeemed us from the curse of the law, being made a curse for us: for it is written, Cursed is every one that hangeth on a tree: 14 That the blessing of Abraham might come on the Gentiles through Jesus Christ; that we might receive the promise of the Spirit through faith.

The example of Abraham’s two sons is another way of defining salvation through faith or the Law.

Abraham in Romans – Faith Is Access to Grace

The Apostle Paul, in the early part of Romans, chapters 1 and 2, eliminated all the forms of righteousness which do not enable forgiveness. Many sentimental funerals emphasize what Paul renounced – “He was a good man. He had a kind heart. He loved his children and the Cubs.” One funeral director grew alarmed when a mobster was preached into heaven by a fill-in minister. The relatives could not connect the praise with his violent history.

Romans Chapter 3

Just like Galatians, Paul argued for Justification by Faith – followed by Abraham as the irrefutable example – Abraham believed the Promise and it was counted by God as righteousness. This righteousness is without the Law and comes by faith of Jesus Christ to all who believe. The Chief Article of the Christian Faith is so clear in this passage that people must insert words and distort the meaning to have it come out the opposite.

KJV Romans 3:21 But now the righteousness of God without the law is manifested, being witnessed by the law and the prophets; 22 Even the righteousness of God which is by faith of Jesus Christ unto all and upon all them that believe: for there is no difference: 23 For all have sinned, and come short of the glory of God; 24 Being justified freely by his grace through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus: 25 Whom God hath set forth to be a propitiation through faith in his blood, to declare his righteousness for the remission of sins that are past, through the forbearance of God; 26 To declare, I say, at this time his righteousness: that he might be just, and the justifier of him which believeth in Jesus.

Those who deny the faith of Jesus are blasphemers and no amount of text distortion and added words can change that sin. Yet Paul has already filled up those bolt holes that are intended by ignorant interpreters to cinch their dogma against the Chief Article. “3:26 To declare, I say, at this time his righteousness: that he might be just, and the justifier of him which believeth in Jesus.”

Justification and faith go together. So Paul uses Abraham to show that grace and faith are together, not opposed to each other. The KJV preserves the truth of the Greek text – the faith of Jesus – even to the point of confounding those who only know “faith in Christ,” which is also in the New Testament.

Romans Chapter 4

Nothing shows the ignorance of false teachers more than pruning a half-sentence from verse 25 and declaring victory. But what did Paul write?

KJV Romans 4:1 What shall we say then that Abraham our father, as pertaining to the flesh, hath found? 2 For if Abraham were justified by works, he hath whereof to glory; but not before God. 3 For what saith the scripture? Abraham believed God, and it was counted unto him for righteousness.

The various Justification by Faith phrases are repetitive because the Chief Article is based upon one verse – and its consequences – in the Old Testament. Sin begins with Adam, but forgiveness starts with Abraham, Genesis 15:6.

Paul wrote these verses, aimed at all the congregations, because of the temptation to make Christianity faith plus works to earn salvation. Abraham is key because of his justification preceding his circumcision.

KJV Romans 4:8 Blessed is the man to whom the Lord will not impute sin. 9 Cometh this blessedness then upon the circumcision only, or upon the uncircumcision also? for we say that faith was reckoned to Abraham for righteousness. 10 How was it then reckoned? when he was in circumcision, or in uncircumcision? Not in circumcision, but in uncircumcision.

This was a major conflict in the Apostolic Age, and seem odd today, but forms of it repeat and flourish today, so it must be understood with child-like faith, not with Barthian-Kirschbaum theology tomes. Imagine an entire volume from Barth and his mistress that starts with “The gift is a demand.”

KJV Romans 4:16 Therefore it is of faith, that it might be by grace; to the end the promise might be sure to all the seed; not to that only which is of the law, but to that also which is of the faith of Abraham; who is the father of us all, 17 (As it is written, I have made thee a father of many nations,) before him whom he believed, even God, who quickeneth the dead, and calleth those things which be not as though they were.

This chapter is only 25 verses long and has so much to say about Abraham and Justification by Faith, naming him seven times.

Everything comes down to the historical fact, that God chose this elderly couple, longing for a son, to have a son when no one could imagine. While this alone was a great miracle for them, the greater miracle was the ultimate blessing for all mankind in providing the Savior in the future by God’s grace and power.

KJV Romans 4:17 (As it is written, I have made thee a father of many nations,) before him whom he believed, even God, who quickeneth the dead, and calleth those things which be not as though they were.18 Who against hope believed in hope, that he might become the father of many nations, according to that which was spoken, So shall thy seed be. 19 And being not weak in faith, he considered not his own body now dead, when he was about an hundred years old, neither yet the deadness of Sarah’s womb: 20 He staggered not at the promise of God through unbelief; but was strong in faith, giving glory to God; 21 And being fully persuaded that, what he had promised, he was able also to perform. 22 And therefore it was imputed to him for righteousness.

Thus, the future of Israel and the Gentile nations depended on the faith of one elderly man and his supposedly infertile wife. God works His miracles among the most unlikely people.

The following verses cannot be adequately understood apart from the entire chapter and the preceding three chapters. Snipping and clipping verses and half-verses is an ideal way to twist the truth but not to explain it.

KJV Romans 4:23 Now it was not written for his sake alone, that it was imputed to him; 24 But for us also, to whom it shall be imputed, if we believe on him that raised up Jesus our Lord from the dead; 25 Who was delivered for our offences, and was raised again for our justification.

We are all beneficiaries of this faith, which gave us, through God’s guidance the Savior, but also the key to understanding the Word of God. We are declared righteous through faith in Him.

Romans 5, The Summary of Romans 4

KJV Romans 5: Therefore, being justified by faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ: 2 By whom also we have access by faith into this grace wherein we stand, and rejoice in hope of the glory of God. 3 And not only so, but we glory in tribulations also: knowing that tribulation worketh patience; 4 And patience, experience; and experience, hope: 5 And hope maketh not ashamed; because the love of God is shed abroad in our hearts by the Holy Ghost which is given unto us.

Abraham in Hebrews

Hebrews is the most eloquent book of the New Testament, constantly referencing the Old Testament. Genesis 15:6 is fulfilled in this unique way –

KJV Hebrews 2:16 For verily he took not on him the nature of angels; but he took on him the seed of Abraham. Wherefore in all things it behoved him to be made like unto his brethren, that he might be a merciful and faithful high priest in things pertaining to God, to make reconciliation for the sins of the people.

Centuries before King David, the Promise was given to Abraham. Centuries after David, the Promise was fulfilled by the Son of David, the Messiah. The Two Natures of Christ are clearly taught, and the Virgin Birth implied in this passage. From a purely human standpoint, the entire New Testament was not based upon Adam, Moses, or the prophets, but upon Abraham – because he was promised to be the forerunner of the Kingdom of Christ and believed that Promise could miraculously overcome the frailties and infertility of old age. He believed and was counted forgiven by God.

Melchizedek

Hebrews gives more space to Melchizedek than the rest of the Bible put together. This caused all kinds of speculation about Melchizedek throughout the ages.

KJV Hebrews 7 For this Melchisedec, king of Salem, priest of the most high God, who met Abraham returning from the slaughter of the kings, and blessed him; 2 To whom also Abraham gave a tenth part of all; first being by interpretation King of righteousness, and after that also King of Salem, which is, King of peace; 3 Without father, without mother, without descent, having neither beginning of days, nor end of life; but made like unto the Son of God; abideth a priest continually.

Lenski’s concise summary is excellent:

The genealogies of Jesus, that of his legal father in Matthew, that of his physical mother in Luke, extend back to royal David and back of that, the former to Abraham, the latter to Adam, and nowhere are there any priestly ancestors; his tribe is that of Judah and not of Levi. The sudden way in which the Scriptures draw back and close the curtain on Melchizedek is the divine way of making him a type of Jesus, the King-Priest, who, like Melchizedek, stands alone and unique in his priesthood and is absolutely distinct from the long Aaronitic succession of priests. Hebrews, p. 213.

Briefly, the lesson in Hebrews 7 is that Christianity does not depend on the Levitical priesthood of the Jews, so the believers should not depend upon or look to Jewish traditions making them the true Christians. In fact, sects and splinter groups still go back to what was left behind, adding required works to guarantee salvation, as Paul feared would happen. Abraham’s unique gift to Melchizedek is a foreshadowing of Jesus as the Great High Priest. Lenski:

The Jews as well as any other readers of this epistle were mistaken if they believed that the laws regarding the Aaronitic priesthood were unalterable and thus also made that priesthood unalterable. These laws rested only on the priesthood. When this priesthood was set aside, the laws of necessity went with it. “Completion” had to be attained; God could not permit inadequate means and laws concerning such means to stand in the way. These means and these laws served their temporary purpose; and when the time came, they had to be changed for something that would be permanent, complete, eternal. Hebrews, p. 224.

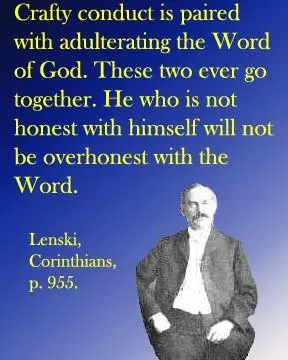

Lenski is very much like Luther in his unified approach to all of Scripture, as distinct from the use and abuse of isolated verses and half-verses to argue a point opposed to the Chief Article of Christianity.*

* Almost anything can be proven with the careful selection of verses and wrongful selection of topics. As Luther wrote, the Bible is a book for heretics.

The Faith Chapter, Hebrews 11

Hebrews 11 is properly called the Faith Chapter for its emphasis upon faith, and Abraham is given a paragraph to emphasize his trust in God, against all human reason:

KJV Hebrews 11:8 By faith Abraham, when he was called to go out into a place which he should after receiving for an inheritance, obeyed; and he went out, not knowing whither he went. 9 By faith he sojourned in the land of promise, as in a strange country, dwelling in tabernacles with Isaac and Jacob, the heirs with him of the same promise: 10 For he looked for a city which hath foundations, whose builder and maker is God. 11 Through faith also Sara herself received strength to conceive seed, and was delivered of a child when she was past age, because she judged him faithful who had promised. 12 Therefore sprang there even of one, and him as good as dead, so many as the stars of the sky in multitude, and as the sand which is by the seashore innumerable.

Whatever Abraham accomplished came by faith in God, so he established an earthly estate – and with Sarah, the future of believers, too numerous to count. And yet he also took, by God’s command, his only son to be sacrificed, to teach all those who followed what it can mean for God to give His only begotten Son. The ram which replaced Isaac on the altar was like Christ on the altar as the substitute for our sins, both the victim and the priest.

KJV Hebrews 11:17 By faith Abraham, when he was tried, offered up Isaac: and he that had received the promises offered up his only begotten son, 18 Of whom it was said, That in Isaac shall thy seed be called: 19 Accounting that God was able to raise him up, even from the dead; from whence also he received him in a figure.

Abraham in James

James 2 contains a passage which the works saints try to kidnap for their benefit. This is good for the logical fallacy of emphasis, so often exploited by false teachers.

KJV James 2:20 But wilt thou know, O vain man, that faith without works is dead? 21 Was not Abraham our father justified by works, when he had offered Isaac his son upon the altar? 22 Seest thou how faith wrought with his works, and by works was faith made perfect? 23 And the scripture was fulfilled which saith, Abraham believed God, and it was imputed unto him for righteousness: and he was called the Friend of God. 24 Ye see then how that by works a man is justified, and not by faith only.

The author was not presenting an argument against Paul, but showing that as a believer, Abraham obeyed the command of God. We could alternately write that faith without works is not genuine faith.

Silencing the Mouths of Rationalists and Apostates

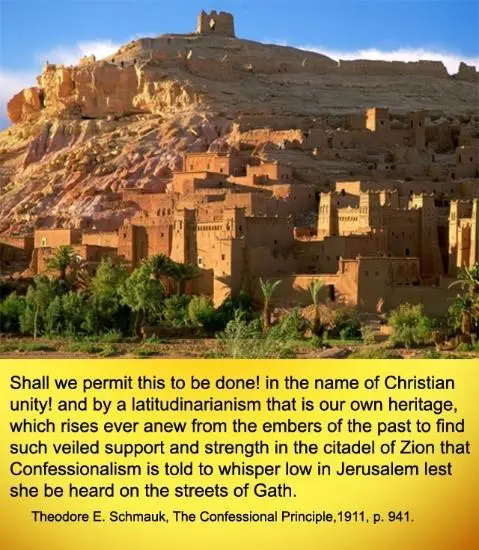

The safest way to talk about the Bible in public is to assume a rationalistic stance and to allow for that, rather than countering it. Worth remembering too are the opponents of Jesus Christ – religious leaders, leaders of His own religion. Between the rationalists and the apostates within, a lifetime of debate is ahead of us.

The Bible Dropping Down from Heaven

A popular beginning is to say, “The Bible is not a book that dropped down from heaven. It is a human book, written down by men.” No one has ever claimed that the Bible floated down from heaven, so this is a straw man logical fallacy – erect a straw man, knock it down, declare victory. The answer is relatively simple – “Yes, it was written by men. I agree with what the Pope said, The Bible has two natures, like Christ, human in being written by men, divine in having no sin or error.”

The Bible Could Have 100 Books or Only Forty.

Columbus, Ohio once boasted a Lutheran seminary with exceptional Biblical scholars – Loy, Leupold, and Lenski. The ALC replaced Lenski with an apostate and the seminary went downhill fast and furious. I visited the seminary bookstore to see if they sold Lenski’s New Testament commentaries. No, they did not, they said – as if that would pollute the students. The store sold books on Romans 1 being fulfilled and volumes on death and dying.

The ALC seminary graduates in the Columbus area liked to preach that the Bible could have 100 books in it or only 40. They never explained which ones they would add – Blessed Rage for Order? The Documents of Vatican II? – or subtract. The clergy used the old arguments from rationalists to prove shocking claims that were already refuted with ease. One of the best counter arguments is to bring up Simon Greentree, the legal scholar who specialized in evidence at Harvard. He began by trying to prove all the contradictions in the resurrections of Christ, but the powerful Word of God defeated him, converted him to the Christian Faith, and made him an example of direct confrontation with the Scriptures.

I Agree with Paul and John about the Virgin Birth

One of the old rationalist responses to the Virgin Birth of Christ is to claim agreement with the Apostles Paul and John about this great miracle, hinting that no such language can be found in either author. This argument would be powerful if it were not so outrageously false. Of course, the skeptics always say that the facts must be in harmony with their way of thinking. Although the Virgin Birth is clearly and unequivocally taught in two Gospels and predicted in Isaiah 7 and 9, a third and fourth match in similar language is demanded.

Paul and the Virgin Birth

Romans 1 begins with the apostolic greeting for his most important doctrinal letter, so the wording is especially clear and universal in scope.

KJV Romans 1:3 Concerning his Son Jesus Christ our Lord, which was made of the seed of David according to the flesh; 4 And declared to be the Son of God with power, according to the spirit of holiness, by the resurrection from the dead:

This description of Christ includes His humanity and descent from King David, but also His divinity as the Son of God. His resurrection from the dead proved His sinless state since death is inevitable for us mortals. Thus, the parallel claim – that Jesus is just a man in the same way the Bible is just a book – fails entirely.

The worst theology comes from the dogmatic books, which are weak on Scriptural knowledge and inclined to soar off into various philosophies rather than sticking with the text itself. Paul’s letter to the Philippians clearly teaches the Two Natures of Christ, and the Virgin Birth is necessarily associated with Jesus being both God and Man –

KJV Philippians 2:5 Let this mind be in you, which was also in Christ Jesus: 6 Who, being in the form of God, thought it not robbery to be equal with God: 7 But made himself of no reputation, and took upon him the form of a servant, and was made in the likeness of men: 8 And being found in fashion as a man, he humbled himself, and became obedient unto death, even the death of the cross.

Some ancient heretics denied the humanity of Christ. Our modern genius dogmatic professors deny the divinity of Christ. Paul teaches both the humanity and the divinity, which can only mean the Virgin Birth. God’s Word addresses our need to see the same lessons from different perspectives. Those who deny the obvious are not content with four Gospels in perfect harmony but want their imaginary dissonance to be praised as beautiful, soothing, and the answer to all questions.

John and the Virgin Birth

The rationalists want to date the Gospel of John as a philosophical book written hundreds of years later. Unfortunately for them, the earliest fragment of the New Testament is dated around 100 AD, and that is a scrap of the Gospel of John. Skeptics are uneasy about the emphasis upon faith in Jesus in the Fourth Gospel. Naturally they would like to remove the divine from the nature of Christ, so they happily declare that John’s Gospel lacks the Virgin Birth narrative.

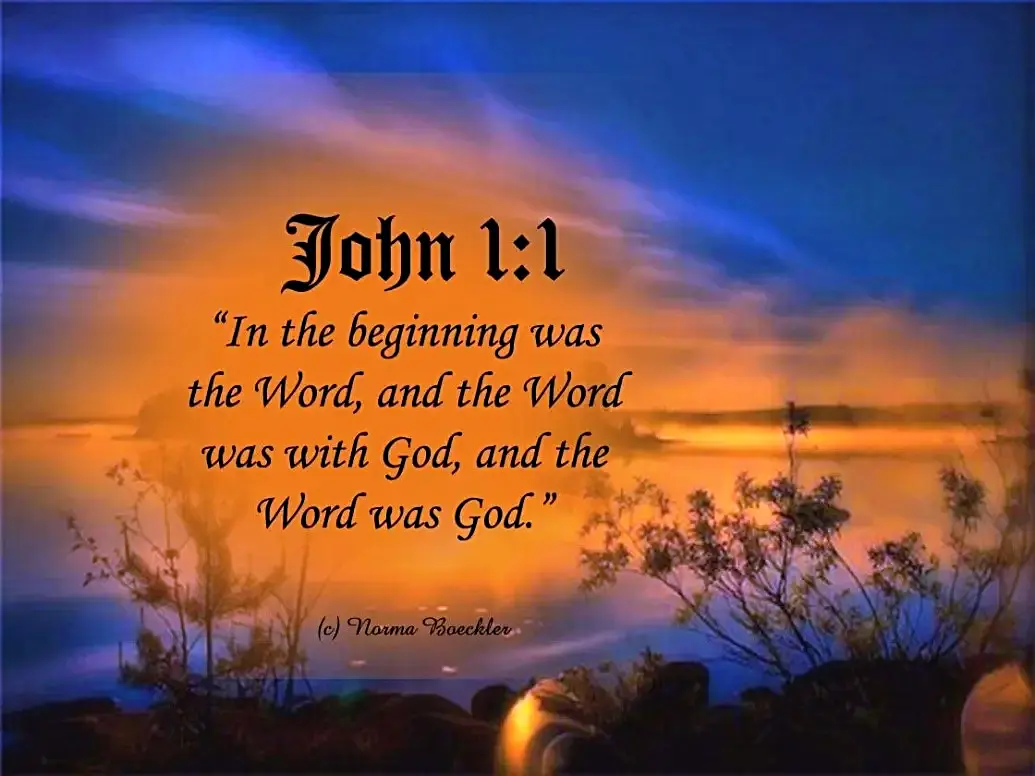

But how does the Gospel start? The first verse echoes the Trinity, with the Word being used three times, like the ringing of great cathedral bells – The Word, the Word, the Word. (Lenski, The Gospel of John.) Jesus is the Word of God, the Logos, as defined in that first verse.

KJV John 1:1 In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. 2 The same was in the beginning with God. 3 All things were made by him; and without him was not any thing made that was made.

Jesus is both man and God, and the Logos (Word) pre- existed the Incarnation. Moreover, this Word – as the Command of God – created everything. Nothing was made apart from Him. To remove the Virgin Birth from the two natures of Christ is bad enough, but this superficial and errant claim is a rejection of the Scriptures and Creation, not a help in understanding anything.

The Holy Trinity

Early in higher education, I heard the Trinity denied as Scriptural, perhaps in college. Two claims are popular – 1) the word Trinity is not in the Bible (true!) and 2) the concept did not become universal until the Council of Chalcedon (false!). I found these assertations so annoying that I included them in some books and devoted one book, The Holy Trinity, to examples from the Scriptures. For the book we used the formula of including the mention of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit within two verses of each other. The Trinity is found throughout the Bible starting with Genesis.

KJV Genesis 1 In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. 2 And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. 3 And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.

When God the Father commanded, the Logos or Son executed the command (John 1:3) and the Spirit bore witness to this Six Day Creation.

Continued in Part IV. The History of the Bible

All sections of The King James Version: Precise Translation versus Fraudulent Texts and Heretical Translations